To Contain Ebola Outbreaks First Train Caregivers – Analysis

The risks are high – Ebola diagnosis, treatment, care should be left to teams of well-trained providers.

By Manisha Juthani-Mehta

Ebola has spread terror because of the lethality of the disease, even more so as the caregivers and physicians on whom patients depend are frequently felled by the malady. To deal with Ebola and other highly contagious diseases that are bound to emerge, a global plan is needed to prepare the caregivers.

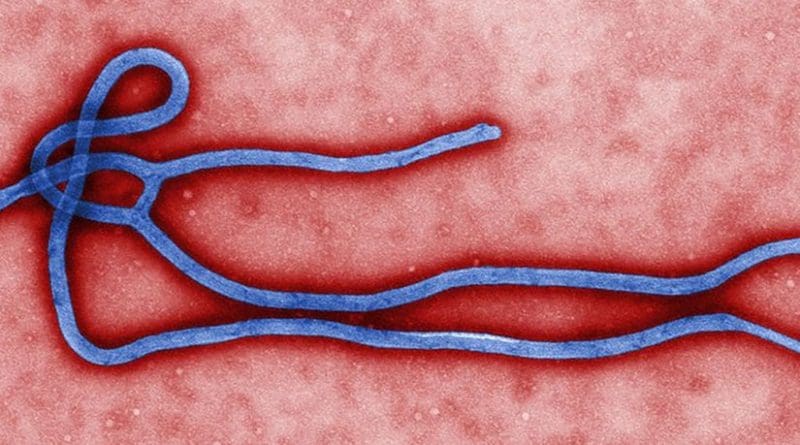

The Ebola virus can be easily transmitted when a patient is symptomatic and highly infectious. Infectiousness increases as the disease progresses, and one fifth of a teaspoon of blood from an actively infected Ebola patient is estimated to contain 10 billion particles of the virus. For healthcare workers, that means that slightly incorrect glove removal followed by a quick brush of one’s eye or wipe of the nose could be deadly.

Meanwhile, disparity in number of caregivers poses challenges: The United States has 2.5 physicians per 1000 people whereas countries like Liberia and Sierra Leone have essentially zero, reports the World Bank. The United States has 9.8 nurses and midwives per 1000 people, while Liberia and Sierra Leone have 0.3 and 0.2, respectively.

Yet, greater numbers of caregivers in the developed world do not provide society automatic protection if they are not well prepared. Two infected in the US were caregivers and not family members of patients, in close proximity during the disease’s early stages. Protection and prior training are essential. Even experienced clinicians do not have experience with the personal protective equipment needed to treat Ebola.

NGOs like Doctors Without Borders, Partners in Health and International Medical Corps send caregivers to infected areas. Safety training sessions, provided by such organizations and the US Centers for Disease Control, are usually three to five days long. As of mid-November, 584 healthcare workers have been infected with Ebola in Africa; 329 have died. Many of these infections have occurred outside of Ebola treatment units rather in other healthcare facilities, highlighting need for protective measures in all settings.

Many caregivers in the developed world are eager to learn and volunteer to care for patients. Such crises are the reason many entered the field, the sentiment expressed by young doctors and nurses as 10 patients with Ebola have been admitted to US hospitals since September.

Trainees fall into a unique category of hospital employees – service providers on the one hand, but learners on the other. A medical trainee is a medical student, resident or fellow. Residents have completed medical school but are not certified in their field, whether that’s internal medicine, surgery or other areas. Fellows have completed residency but are still in training in a subspecialty, such as infectious diseases, cardiology, gastroenterology and more. The dilemma is that trainees, except students, are doctors and therefore providers. But they are still learning, in training.

From 2011-2012, in the United States, there were 115,293 residents in training in 9,022 programs, and trainees constitute over 10 percent of the physician workforce.

Hospitals must look after caregivers’ best interests, take necessary precautions, institute appropriate training, and only allow them to participate in high-risk circumstances after such steps are taken. Physicians are not the only ones placing themselves at risk. Nursing staff, who provide the majority of care to critically ill patients, have realized the risks they face without appropriate training, some going so far as to strike to shed light on this issue. Blood tests are challenging since an entire laboratory could get contaminated. Point-of-care testing, lab tests that can be performed at the bedside, have reduced this risk. Even cleaning crews place themselves at risk in handling infected equipment, needles and bodily waste.

Even with appropriate training in the use of personal protective equipment, the Ebola virus can be easily transmitted when patients are symptomatic and highly infectious.

The ninth identified Ebola patient in the United States, Craig Spencer, a physician who received training and was working in Guinea with Doctors Without Borders, Médecins Sans Frontières, was discharged in good health. The 10th patient, Martin Salia, a surgeon working in his native Sierra Leone, was the second Ebola death in this country despite intensive medical care late in the course of his disease. Though fiancées of two Ebola patients remain healthy, two nurses in a Texas hospital contracted the disease while treating a patient in the advanced stages.

Such experiences show the ease with which Ebola can be transmitted to healthcare workers when patients are acutely ill. Hospitals must decide whether their trainees should participate in the care of such patients. Many hospitals, including Yale-New Haven Hospital, have decided to keep all students, residents, and fellows out of the evaluation process of a patient with suspected Ebola – a sensible protocol.

After a series of missteps, the CDC finally updated guidelines for the use of personal protective equipment in US hospitals, which takes advantage of the experience of aid organizations with Ebola patients. With this guidance, U.S. hospitals establish local patient care protocols and training modules. In many such institutions, small groups of individuals are being trained to care for these patients, thereby minimizing the number of those placed at risk. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education also announced that trainees should receive such training.

All healthcare workers chose their professions, at some level, to help others. When they made the decision to be trained as doctors, nurses or other providers, they knew the potential risk of exposure to contagious infectious diseases. Healthcare providers have a moral and ethical obligation to care for the ill.

But before helping others, caregivers must help themselves. In healthcare settings, first responders and critical care providers must be prepared first, and then additional staff can be trained as time and resources permit. Supplies are on backorder, and hospitals are trying to optimize the use of their equipment.

MSF requires that physicians working in the field have completed a residency program, and it’s logical that the same requirement should hold true elsewhere for those providing care to suspected Ebola patients. Similarly, nurses must hold an appropriate degree with a valid license to volunteer with MSF. Trainers in U.S. hospitals are currently overloaded in efforts to get the front line ready and waiting.

As well intentioned as the desires of many trainees may be, their desires must come second. For trainees, especially those entering fields such as emergency medicine, critical care and infectious diseases, the first obligation is to keep them safe while they treat others. But the first priority for hospitals treating suspected Ebola patients is effective care for those affected by the disease.

In the next several months, hospitals around the country will train small teams of providers. Occasional cases of Ebola in the United States and other developed countries are likely until the outbreak is controlled in West Africa. Trainees who want to volunteer should be trained as well. But we aren’t there yet.

If Ebola were to hit a densely populated developing nation such as India or China, the consequences could be devastating. Although these countries are taking the necessary steps to prepare, NGOs and the US government should have teams of well-trained, experienced providers ready to deploy to these nations to help control the spread of this outbreak any further.

Manisha Juthani-Mehta is an associate professor and director of the Infectious Diseases Fellowship Program in the Section of Infectious Diseases at Yale School of Medicine. She is an OpEd Project Public Voices Fellow.