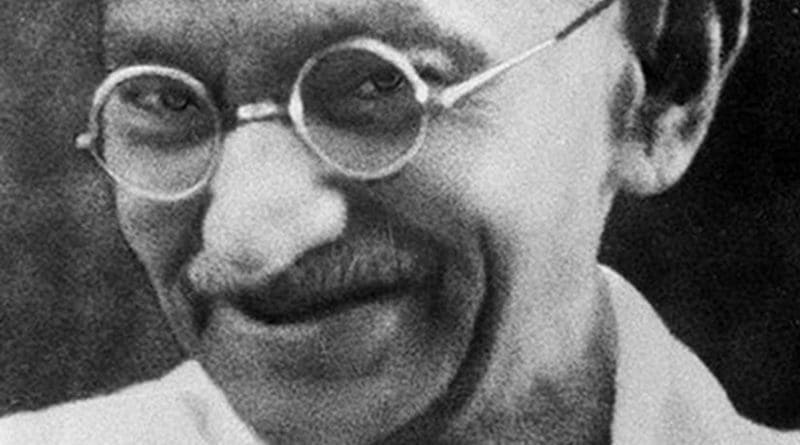

How Gandhi Made A Political Philosophy Out Of Goodness – OpEd

By Prakash Kona

Gandhi’s assassin Nathuram Godse has the look of the prodigal son who wishes to be absolved of the guilt of taking a man’s life. His justification for killing the Mahatma appeals to a paternal sense of benevolence from the audience as can be seen in his final address to the court that sentenced him to death. Since Gandhi played the role of a father and a father-figure his entire life, it is not surprising that his assassin should have the kind of dramatic impact on the audience in the courtroom, who were in tears while he spoke, as recollected by one of the judges, who noted, “I have, however, no doubt that had the audience of that day been constituted into a jury and entrusted with the task of deciding Godse’s appeal, they would have brought a verdict of ‘not Guilty’ by an overwhelming majority.”

If Gandhi was conscious for a few more hours or lived a couple of more days, I am sure that Nathuram Godse would have received an “honorable discharge” and upon Gandhi’s behest might also have been rewarded in some ways. Such is the goodness of Gandhi whatever else his politics might have been. “Intellectually, some others have surpassed him, but ethically he is supreme” – is what Bertrand Russell said of Spinoza in The History of Western Philosophy. The same can be rephrased about Gandhi: Politically, some others have surpassed him, but ethically he is supreme, so much so that he can look at his own assassin with pity and humanity. The modern world, with its cancel and woke cultures, is starved of both pity and humanity.

It amazes me that there are people who hate Gandhi with the might of their souls. In fact, I’ve never met too many Indians who thought well of him and the kind of virulent attacks he is subjected to by various groups, is mind-numbing. As ironic as it may sound, the people who kept the memory of the man and his message alive, happen to be largely white Europeans and North Americans; the very people that Gandhi stood opposed to all his life. In India of course Gandhism has never been anything more than lip service to some abstract notion devoid of any practicality. There might be some truth in what one of his biographers Krishna Kriplani said:

“The brave honour the brave. Gandhi defied and fought the British, he was fair and straight with them, and they honoured him for it, even when they had to lock him up behind the bars. General Smuts was his classic antagonist and admirer. The antagonism was open and the admiration mutual. As the General’s prisoner in the Johannesburg jail, Gandhi had made with his own hands a pair of sandals which he sent as a gift to him before sailing from South Africa in 1914. Recalling the gesture twenty-five years later, General Smuts wrote: ‘I have worn these sandals for many a summer since then, even though I may feel that I am not worthy to stand in the shoes of so great a man.’”

Cowardly, cynical and morally bankrupt people cannot understand how difficult it is to live like Gandhi for a day. This is what made Gandhi’s cold-blooded murder unforgivable in the eyes of the court that awarded the death sentence to his assassin. Of course there is a larger question to Gandhi’s death, which is, how do we understand the whole question of goodness and relate it to his work. Does goodness matter? Can goodness be a political weapon to fight an unjust opponent occupying a position of power? Is goodness meaningful in a world where it is unrealistic to be good? Should goodness be treated as an important criterion in how we measure people? What, in fact, is goodness? The young priest at the end of the movie Chocolat (2000) summarizes it poetically, when he says: “I think that we can’t go around…measuring our goodness by what we don’t do. By what we deny ourselves, what we resist, and who we exclude. I think…we’ve got to measure goodness by what we “embrace”, what we create…and who we include.”

Goodness is the ability to embrace, to include and to create, irrespective of what religion, caste or political ideology someone might claim to espouse. In other words, what people do and how they are, in terms of their actions and behavior, with those around them is much more important than what they claim to represent. I would rather have a friendly, accommodative and kind neighbor who is completely opposed to me politically and ideologically, than an unkind and dishonest person who believes in everything that I do and belongs to the social group that I come from. Life is much more bearable with good people around rather than those who are guided by their own personal notions of right and wrong. Frankly, beyond a point, it’s a headache to spend time with people who are caught up with themselves to such an extent that they find it difficult to accept others, who are unlike them. That is the context to Gandhi’s goodness: how you live and what you do to improve the lives of others is the only measurement of who you really are.

A man like Gandhi who lived his life free of hatred and rancor, was also free of fear. When there is no hatred, what is there to fear! As simple as this may sound this is a goodness that unconditionally embraces, includes and creates. Although Gandhi deeply believed and identified himself as a Sanatanist Hindu and is undoubtedly one of Hinduism’s formidable interpreters in the 20th century along with Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Swami Prabhavananda, his willingness to include Christianity and Islam as a practicing Hindu, ought to be viewed in the light of his belief that goodness had no particular religion or could be seen equally in all religions.

Edmund White observed that the French writer “Genet, who in his fiction seemed such a champion of evil, once responded, when asked what he considered the most important human trait, ‘Goodness.’” Gandhi’s own understanding of goodness as the most important human trait rests on his conviction that being good need not necessarily bring the desired results. Gandhi knew that the human heart was capable of infinite evil. That people would do anything to justify their darkest intentions is something he was not deluded about. Gandhi’s goodness is not coming from a false notion that people could change just like that and become better overnight. On the contrary, Gandhi is able to recognize that goodness also means failure in the real world. That’s how we need to look at Gandhi’s own goodness and his belief in such goodness.

To be good is to be prepared for failure and defeat. Contrary to wishful thinking that good is rewarded and evil punished, evil most of the time goes unpunished and there is ample evidence that it succeeds in an actual situation. Proofs for the success of goodness are rather scarce when compared to the success of evil that is documented as history. Goodness does not succeed in the sense that we understand success where we see concrete proof for something that happens. That’s what makes evil dangerously attractive and goodness implausibly naive. Good people fail and are put on the rack. There are no rewards for being good. To expect any such rewards is pointless. Evil men are not thinking of consequences. They want results here and now. Goodness haunts the souls of men and women not with results but with consequences, both emotional and spiritual.

I want to take two instances where evil succeeds in the real world. Standing at the gates of Rome, the almost invincible Carthaginian general Hannibal refused to devastate the city, a move that would’ve changed the course of history. “Hannibal repeatedly stressed that he was not fighting to destroy Rome, but for ‘honour and power’, desiring to remove the limitations imposed on Carthage after the First War and reassert her dominance in the western Mediterranean.” It was however a mistake that the Romans would not make at the point when they destroyed the great North African civilization under the brutal consul Cato the Elder, reducing Carthage to rubble. With a characteristic existential angst, Borges notes in one of his poems “And the steadily flowing Rhone and the lake,/ All that vast yesterday over which today I bend?/ They will be as lost as Carthage,/ Scourged by the Romans with fire and salt.” Hannibal’s reluctance to destroy Rome when he had the chance to do so came with a heavy price.

At the peak of the Arab Islamic Renaissance, the Mongols under Genghis Khan and his descendants destroyed the intellectual centers of the known world. The city of Baghdad to which we perhaps owe the central tenet of humanism – that each one is as much of a human being as any other – was razed to the ground, its rivers turning into red with the blood of the people and then black with the ink from its books.

In both the cases, the destruction is meaningless and the victims in no way deserving of such cruelty. When Gandhi looks at history, he is looking at how people have treated each other since the very beginning. Being opposed to colonialism is only one part of the fight against evil. But, slavery and colonialism, are not the only evils that men have committed for thousands of years. When the partition of India took place, ordinary Indians – both Hindus and Muslims – committed unthinkable acts of violence against each other. Perhaps the last days of British rule of India created the conditions for such violence. That however does not excuse the individuals going against the dictates of their conscience and doing unforgivable things.

That’s how we need to look at Gandhi. It’s not about merely British rule of India but it is about transforming human nature and making it human. Of course, Gandhi believed that only through religion was it possible to humanize the masses. But, then, I am certain he was aware that in the name of religion people have murdered, raped, looted and destroyed without even the slightest trace of guilt, as happened during India’s partition. In fact, his own assassin, who apparently was a staunch believer, did not hesitate to pull the trigger on him. Judith M. Brown called her biography of the Mahatma, Gandhi: Prisoner of Hope. Gandhi’s life is essentially the story of a failure who made a political philosophy out of goodness. Therefore, the hope against all odds that human nature can be transformed through acts of goodness despite the failures one encounters in the process, as Gandhi did.