Occupied Ukraine: Priest Killed Within Two Days Of Russian Detention

By F18News

By Felix Corley

Unknown men from the Russian occupation forces seized 59-year-old Fr Stepan Podolchak of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine on 13 February in the Ukrainian village of Kalanchak in the Russian-occupied part of Kherson Region. They took him away barefoot with a bag over his head, insisting he needed to come for questioning. His bruised body – possibly with a bullet-wound to the head – was found on the street in the village on 15 February and taken to the morgue. Morgue staff phoned his wife to identify the body.

Fr Stepan’s family buried his body in Kalanchak on Sunday 18 February (see below).

Serhy Danilov, who worked on projects to support civil society in Kherson Region from 2014, told Forum 18 he thinks the men who seized Fr Stepan were from the Russian Interior Ministry’s Centre for Countering Extremism. He thinks from knowledge of other people seized by the Russians that they might have taken Fr Stepan to the detention centre at nearby Chaplinka (see below).

Fr Stepan’s body showed signs of bruising and traces of having been in handcuffs, Danilov said. Some reports he had received said Fr Stepan’s body had a bullet-wound to the head. The death certificate issued to the family claimed that Fr Stepan had died of a heart attack, Danilov added (see below).

Bishop Nikodim (Kulygin) of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine’s Kherson and Tavria Diocese (the diocese neighbouring Fr Stepan’s Kherson and Kakhovka Diocese) told Forum 18 that Russian occupation forces “tortured Fr Stepan to death” (see below).

“The Russians tortured him to death,” Svitlana Fomina, the head of the exiled Kalanchak village military administration (which operates from Ukrainian government-held territory), told the Kyiv-based Centre for Journalistic Investigations. “He was always pro-Ukrainian, conducted all services in Ukrainian, prayed for Ukraine, even under occupation. Apparently, because of this, the Russians took away the most valuable thing that a person has – life” (see below).

When Forum 18 on 19 February asked Kalanchak’s Russian police what action they have taken or will take following the killing of Orthodox Church of Ukraine priest Fr Stepan, the duty officer (who did not give his name) replied: “For a long time this [community] hasn’t existed here and won’t. Forget about it.” He then put the phone down (see below).

The official who answered the phone at the Russian Investigative Committee of Kherson Region, who did not give his name, refused to answer Forum 18’s questions about the death of Fr Stepan by phone. “Fill in the form on our website,” he told Forum 18. “We will respond within the required 30 days” (see below).

Through the Russian Investigative Committee website, Forum 18 noted the suspicions of local people that Fr Stepan might have been tortured to death and asked:

– whether an investigation into Fr Stepan’s death is underway and, if so, which agency is conducting it;

– whether a criminal case has been opened and, if so, under what Criminal Code article;

– whether anyone has been arrested already and, if so, how many people.

Forum 18 has received no response (see below).

Under the United Nations (UN) Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Russia is obliged both to take into custody any person suspected on good grounds of having committed torture “or take other legal measures to ensure his [sic] presence”, and also to try them under criminal law which makes “these offences punishable by appropriate penalties which take into account their grave nature”. This routinely does not happen, including when the torture happens within Russia’s internationally-recognised borders (see below).

Fr Stepan chose to remain in Kalanchak to serve his community after the Russian occupation of much of Ukraine’s Kherson Region in early 2022. “Fr Stepan was someone who felt he couldn’t abandon his people,” Danilov told Forum 18. Russian officials banned his community from continuing to use a rented room in Kalanchak’s House of Culture. Fr Stepan continued to lead services in the half-finished church he was building (see below).

“The [Russian] police and FSB repeatedly pressured Fr Stepan to move to the Moscow Patriarchate,” Danilov told Forum 18. “He told them he couldn’t betray his oath and community” (see below).

Russian occupation officials have often threatened religious leaders if they refuse to renounce their allegiance to religious bodies they do not like. Russian occupation officials dislike the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, and religious communities of any faith which remain part of communities with headquarters in Ukrainian government-held territory (see below).

Russian occupation forces have also kidnapped, tortured, and killed other Ukrainian religious community leaders since the February 2022 renewed Russian invasion (see below).

More than 10 years’ service in Kalanchak

Fr Stepan Podolchak was a priest of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine in the village of Kalanchak in the southern Skadovsk District of Kherson Region. The Orthodox Church of Ukraine was recognised as canonical by the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 2019. It is separate from the Russian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate and its affiliate in government-held Ukraine, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church.

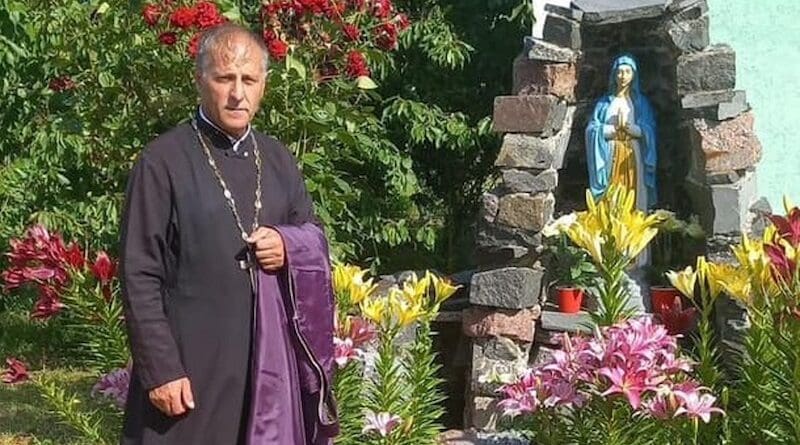

The 59-year-old priest, who was married with children and grandchildren, was originally from Lviv Region in western Ukraine and was ordained priest in 1998. He had served for more than ten years in Kalanchak.

Fr Stepan held services in a rented room in Kalanchak’s House of Culture until the Russian invasion of the area in spring 2022. Soon after the occupation, the Russians banned him from continuing to use the rented premises. He then held services in the half-finished Church of All the Holy Lands which he was building in Kalanchak.

“Fr Stepan had built the walls and was trying to complete the building,” Serhy Danilov told Forum 18. Danilov is a Kyiv-based anthropologist who worked on projects to support civil society in Kherson Region from 2014.

Remained after Russian occupation

After the occupation of most of Kherson Region soon after Russia launched its renewed invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Fr Stepan chose not to flee to Ukrainian government-held territory. He continued to serve in the village and continued to conduct the liturgy in Ukrainian as a priest of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine.

“Fr Stepan was someone who felt he couldn’t abandon his people,” Serhy Danilov told Forum 18. “He felt responsible for them.”

The Russian occupation forces repeatedly pressured Fr Stepan to transfer from the Orthodox Church of Ukraine to the Moscow Patriarchate Russian Orthodox Church. (The Moscow Patriarchate has unilaterally transferred some dioceses from its branch in Ukraine – the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – to be directly subject to the Patriarch in Moscow.)

“The [Russian] police and FSB repeatedly pressured Fr Stepan to move to the Moscow Patriarchate,” Danilov told Forum 18. “He told them he couldn’t betray his oath and community.”

Russian occupiers’ targeting of religious community leaders

Russian occupation officials have often threatened religious leaders if they refuse to renounce their allegiance to religious bodies they do not like. Russian occupation officials dislike the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, and religious communities of any faith which remain part of communities with headquarters in Ukrainian government-held territory.

Russian occupation officials tried to pressure two priests in occupied Donetsk Region – Fr Khristofor Khrimli and Fr Andri Chui – to transfer from the Orthodox Church of Ukraine to the Russian Orthodox Church.

Fr Khristofor and Fr Andri were arrested in September 2023 by officials of a Russian FSB department which controlled the exercise of freedom of religion or belief. “Officials told them that if they renounce the Orthodox Church of Ukraine and repent of their affiliation with it on camera, and transfer to the Moscow Patriarchate and undergo re-ordination, they would give them a good parish where they would enjoy a good standard of living,” Metropolitan Serhy (Horobtsov) told Forum 18 in January 2024. Both priests refused.

Fr Khristofor and Fr Andri were fined and ordered deported for conducting “illegal missionary activity”. They were illegally transferred from occupied Donetsk Region to Russia’s Rostov Region, where they are being held in the Deportation Centre in the village of Sinyavskoe in Neklinovsky District. They refused to be deported to Latvia, insisting that they wished to return to Donetsk.

Russian occupation forces have also kidnapped, tortured, and killed other Ukrainian religious community leaders since the February 2022 renewed Russian invasion. Such cases include the March 2022 torture of Imam Rustem Asanov, a Crimean Tatar, of the Birlik (Unity) Mosque in the village of Shchastlivtseve in Henichesk District in Ukraine’s Kherson Region. Imam Asanov was pressured in Russian detention to cut the mosque community’s ties to the Spiritual Administration in Kyiv, and subjugate his mosque community to the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Crimea in the occupied Ukrainian city of Simferopol.

Russian occupation forces forced the mosque to close.

On 22 November 2022, the Russian military seized a businessman and Pentecostal deacon 52-year-old Anatoly Prokopchuk and his 19-year-old son Aleksandr Prokopchuk, who lived in Nova Kakhovka in Kherson Region. On 26 November, their shot and mutilated bodies were found in a nearby wood. Russian occupation officials refused to answer Forum 18’s questions about the torture and killing of the Prokopchuks.

On 8 November 2023, the three UN Special Rapporteurs on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association, on minority issues, and on freedom of religion or belief wrote to the Russian authorities (AL RUS 25/2023) expressing their “serious concern for the alleged enforced disappearances and torture or ill-treatment of clergy in the occupied territories in violation of international human rights law”, and other freedom of religion or belief violations.

Russia replied to the UN on 21 November that “all requests made in a manner offensive to the authorities and population of the Russian Federation, using language that is inconsistent with the principle of respect for the Constitution of the Russian Federation and the territorial integrity of Russia, will be left unanswered”.

Seized on Tuesday, body found on Thursday

On 13 February 2024, Russian occupation forces arrived at Fr Stepan’s home in Kalanchak and searched it, taking away several boxes of items. The men then took him away without saying where they were taking him, Svitlana Fomina, head of exiled Kalanchak village military administration (which operates from Ukrainian government-held territory), told the Kyiv-based Centre for Journalistic Investigations on 15 February. The armed men put a bag over Fr Stepan’s head before taking him away barefoot.

Although the men who took him did not identify themselves, Serhy Danilov thinks they were from the Russian Interior Ministry’s Centre for Countering Extremism. He thinks from knowledge of other people seized by the Russians that they might have taken Fr Stepan to the detention centre at Chaplinka, 25 kms (15 miles) to the north-east. “The Russians have taken many prominent people to the detention centre there, which has a large bunker,” Danilov added.

On 15 February, Fr Stepan’s body was found on the street in Kalanchak, Danilov added. Officials took the body to the morgue for it to be identified. “On 15 February, his wife was called and ‘invited’ to come and identify the body of the deceased husband,” Fomina said.

Danilov said Fr Stepan’s body showed signs of bruising and traces of having been in handcuffs. Some reports he had received said Fr Stepan’s body had a bullet-wound to the head. The death certificate issued to the family claimed that Fr Stepan had died of a heart attack, Danilov added.

Fr Stepan’s family buried his body in Kalanchak on Sunday 18 February.

“For a long time this [community] hasn’t existed here and won’t”

When Forum 18 on 19 February asked Kalanchak’s Russian police what action they have taken or will take following the killing of Orthodox Church of Ukraine priest Fr Stepan, the duty officer (who did not give his name) replied: “For a long time this [community] hasn’t existed here and won’t. Forget about it.” He then put the phone down.

Forum 18 was unable to speak to the head of the Russian occupation Skadovsk District Police, Sergei Naberezhny. Officials in a different Interior Ministry department there refused to give Forum 18 his number on 19 February. Forum 18 was also unable to reach the Russian Interior Ministry’s Centre for Countering Extremism in occupied Kherson Region.

The Russian occupation official who answered the phone at the Russian Investigative Committee of Kherson Region, who did not give his name, refused to answer Forum 18’s questions about the death of Fr Stepan by phone. “Fill in the form on our website,” he told Forum 18 from Henichesk on 19 February. “We will respond within the required 30 days.”

Told that it was unknown who had taken Fr Stepan – whether the Russian military, Rosgvardiya, the FSB security service or the police – the official answered: “We don’t deal with the military – that would be the Military Investigative Department. If a crime is committed by the police or civilians, then we would investigate.”

Through the Russian Investigative Committee website, Forum 18 noted the suspicions of local people that Fr Stepan might have been tortured to death and on 19 February asked:

– whether an investigation into Fr Stepan’s death is underway and, if so, which agency is conducting it;

– whether a criminal case has been opened and, if so, under what Criminal Code article;

– whether anyone has been arrested already and, if so, how many people.

Forum 18 had received no response by the end of the working day in Henichesk of 20 February.

Under the United Nations (UN) Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Russia is obliged both to take into custody any person suspected on good grounds of having committed torture “or take other legal measures to ensure his [sic] presence”, and also to try them under criminal law which makes “these offences punishable by appropriate penalties which take into account their grave nature”.

This routinely does not happen, including when the torture happens within Russia’s internationally-recognised borders.

“The Russians tortured him to death”

Bishop Nikodim (Kulygin) of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine’s Kherson and Tavria Diocese (the diocese neighbouring Fr Stepan’s Kherson and Kakhovka Diocese) told Forum 18 on 16 February that Russian occupation forces “tortured Fr Stepan to death”.

(Bishop Nikodim himself lived under Russian occupation in the town of Oleshky from the time Russian forces invaded in early 2022 until 17 July 2023, he told Forum 18.)

“The Russians tortured him to death,” Svitlana Fomina, head of the exiled Kalanchak village military administration (which operates from Ukrainian government-held territory), also insists. “He was the brightest person I was lucky enough to meet in my life. He is like an angel who came down to earth – faithful to God, pure in soul, honest and just.”

“He was always pro-Ukrainian, conducted all services in Ukrainian, prayed for Ukraine, even under occupation. Apparently, because of this, the Russians took away the most valuable thing that a person has – life,” Fomina told the Centre for Journalistic Investigations.