1789: The First Thing The New American Government Did Was Impose A Huge Tax Increase – OpEd

By MISES

By Joshua Mawhorter*

It may come as a surprise—though it should not—that one of the very first acts of the new Congress, under the Constitution, was a tax program at least as great as the one imposed on the colonies by Great Britain. It turned out that taxation with representation could be just as oppressive as taxation without representation or worse.

It is supreme irony that the very first major act of the new Congress was taxation at a level that would have made Britain proud. The only thing that happened on June 1, 1789, contained in the first chapter of the first session was an act to fix a time for US government officials—senators, house members, judges, etc.—to take their oaths. The real business took place over the next month, and a new bill was signed into law by George Washington on July 4, 1789.

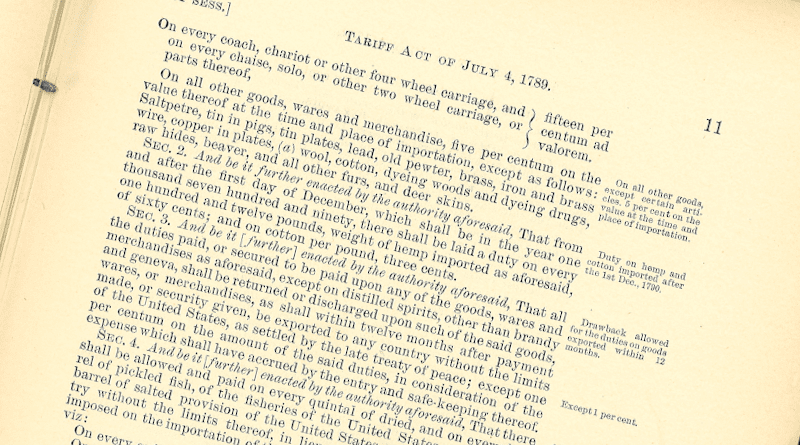

During the first session of Congress taxes were imposed on the states in the Tariff Act of 1789. It is acknowledged that the new Constitution was given the power to tax and that this was one of the main differences between it and the government under the Articles of Confederation. We should note, however, that the Constitution laid out specific reasons that the¢ral government could tax the people. These stipulations can be found in the US Constitution, under Article I, Section 8. These powers include the payment of war debts and other specific purposes. The powers of taxation in the Constitution, however, were limited to what is listed in that section, and its proponents said that the taxing powers were few and plainly defined.

The Tariff Act of 1789 contains taxation for constitutional purposes and taxation for unconstitutional purposes in the same act. This is a common government tactic in all ages to justify excessive taxation. For example, the National School Lunch Act of 1946, which has been extended to this day, mixes the purpose of well-being of children and their nutrition with encouraging and artificially subsidizing certain agriculture companies. In the introduction to the Tariff Act of 1789, officially called An Act for Laying a Duty on Goods, Wares, and Merchandises Imported into the United States, we can read the reason for which these taxes were created,

SEC. 1. Whereas it is necessary for the support of government, for the discharge of the debts of the United States, and the encouragement of manufactures, that duties be laid on goods, wares and merchandise imported …

Those who have a knowledge of Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution will be able to recognize which section is provided for in the Constitution and which is not, but a hint will be given below to make the point:

SEC. 1. Whereas it is necessary for the support of government, for the discharge of the debts of the United States, and the encouragement of manufactures, that duties be laid on goods, wares and merchandise imported … (emphasis added)

The bold section is a purpose mentioned in the Constitution for which the government can raise a legitimate tax.

SEC. 1. Whereas it is necessary for the support of government, for the discharge of the debts of the United States, and the encouragement of manufactures, that duties be laid on goods, wares and merchandise imported … (emphasis added)

The bold section emphasized in the second quotation is not a legitimate constitutional reason for the government to tax the people. This type of thinking—that domestic businesses need protection by the government from foreign competition and that infant industries cannot survive without government help—is the product of an economic system called mercantilism. Protectionist tariffs—taxes on foreign imports that raised the prices for domestic consumers—allowed domestic businesses to sell to the people at higher prices.

This was the position of Alexander Hamilton, who gave us our modern government through his theories of protectionism. This was picked up by Lincoln and the Republican Party, whose platform had always been built around tariffs—at the disproportionate expense of the South—in order to protect Northern manufacturing industries from foreign competition and fund government projects. It was a reaction to this from the Southern populists that brought about the Sixteenth Amendment, the income tax, in 1913. The Southern farmers, who were overburdened with tariffs that benefited Northern industry, thought the income tax would only affect wealthy Northerners. What was the result? The burdens from both tariffs and the income tax increased on everyone.

Mercantilism and protectionism are filled with corruption and allow the government to pick and choose favorite companies to give special treatment to at the expense of the taxpayer. Conversely, businesses may become unduly involved in government by gaining and using political power. This system also becomes entrenched because it protects—in a perverse way—jobs.

Fewer choices and higher prices make us poorer, not richer. This was the first substantial decision made by the constitutional government, to tax the items below listed:

- Distilled spirits, Jamaica proof—10¢ per gallon

- Other distilled spirits—8¢ per gallon

- Molasses—2.5¢ per gallon

- Madeira wine—18¢ per gallon

- Other wines—10¢ per gallon

- Beer, ale, or porter in casks—5¢ per gallon

- Cider, beer, ale, or porter in bottles—20¢

- Malt—10¢ per bushel

- Brown sugars—1¢ per pound

- Loaf sugars—3¢ per pound

- Other sugars—1.5 per pound

- Coffee—2.5¢ per pound

- Cocoa—1¢ per pound

- Candles of tallow—2¢ per pound

- Candles of wax or spermaceti—6¢ per pound

- Cheese—4¢ per pound

- Soap—2¢ per pound

- Boots—50¢ per pair

- Shoes, slippers, or galoshes made of leather—7¢ per pair

- Shoes or slippers made of silk—10¢ per pair

- Cables—75¢ per 112 pounds

- Tarred cordage—75¢ per 112 pounds

- Untarred cordage and yarn—90¢ per 112 pounds

- Twine or packthread—200¢ per 112 pounds

- Unwrought steel—56¢ per 112 pounds

- Nails and spikes—1¢ per pound

- Salt—6¢ per bushel

- Manufactured tobacco—6¢ per pound

- Snuff—10¢ per pound

- Indigo—16¢ per pound

- Wool and cotton cards—50¢ per dozen

- Coal—2¢ per bushel

- Pickled fish—75¢ per barrel

- Dried fish—50¢ per quintal

Teas from China or India:

- Bohea Tea—6¢ per pound

- Souchong or black teas—10¢ per pound

- Hyson teas—20¢ per pound

- Other green teas—12¢ per pound

Teas imported from Europe:

- Bohea tea—8¢ per pound

- Souchong or black teas—13¢ per pound

- Hyson teas—26¢ per pound

- Other green teas—16¢ per pound

Teas imported in a different manner:

- Bohea tea—15¢ per pound

- Souchong or black teas—22¢ per pound

- Hyson teas—45¢ per pound

- Other green teas—27¢ per pound

Goods, wares, and merchandises (other than tea) imported from China or India:

- Looking glasses and window and other glass (except black quart bottles)—10% of price

- China, stone, and earthenware—10% of price

- Gunpowder—10% of price

- Oil paints—10% of price

- Shoe and knee buckles—10% of price

- Gold and silver lace—10% of price

- Gold and silver leaf—10% of price

- Blank books—7.5% of price

- Writing, printing, or wrapping paper—7.5% of price

- Paper hangings and pasteboard—7.5% of price

- Cabinet wares—7.5%

- Buttons—7.5%

- Saddles—7.5%

- Leather gloves—7.5%

- Hats of beaver fur, fur, wool, or a mix—7.5%

- Ready-made millinery—7.5%

- Castings of iron, slit, and rolled iron—7.5%

- Leather (tanned or tawed or manufactured)—7.5%

- Canes, walking sticks, and whips—7.5%

- Ready-made clothing—7.5%

- Brushes—7.5%

- Gold, silver, plated ware, jewelry, and paste work—7.5%

- Anchors, wrought, tin and pewter ware—7.5%

- Playing cards—10¢ per pack

- Coaches—15%; chariots—15%; other four-wheel carriages—15%; Chaise, solo, or two-wheel carriages—15%

- On all other goods, wares, and merchandise, five per centum on the value thereof at the time and place of importation …

Also,

- From December 1, 1790 onward: hemp—60¢ per 112 pounds; cotton—3¢ per pound (section 4)

- Dried fish—5 cents per quintal; Pickled fish—5 cents per barrel; Salted provisions—5 cents per barrel (section 5)

Section 5 provided for a 10 percent discount on the duties mentioned above if the ships on which these goods traveled were built in the United States and wholly belonged to the citizens of the United States or were built in foreign countries but belonged to the United States after May 16, 1790.

Section 6 stated that the act would continue until June 1, 1796.

All these items—including tea—were taxed by the United States government. Ironically, the act was signed on July 4, 1789—exactly thirteen years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Thirteen years after the colonies seceded from Britain to become independent states because of (among other things) an unfair tax burden and monopolistic trade restrictions, the new government formed between them through the Constitution followed the same pattern.

This should not be a surprise. What ultimately drew George Washington to the Philadelphia Convention (1787)—when so many previous plans for conventions to revise the Articles had failed—was alarm over a tax revolt called Shays’s Rebellion. Washington himself—with the urging of Alexander Hamilton—set the precedent of using federal force (thirteen thousand men) to put down a local tax revolt in the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791. The Whiskey Rebellion was, in fact, a direct result of the Tariff of 1789.

This precedent led invariably to the war that took the lives of more Americans than all wars from that time until the 1990s—the Civil War. While slavery cannot be discounted, it does not seem accurate to ignore the tax issue of the Civil War. The priorities of Lincoln—if we follow his First Inaugural Address—were willingness to negotiate on the issue of slavery but unwillingness to negotiate on tax revenue. Lincoln was willing to subjugate on the issue of taxes and revenue, and this has been the norm of the US federal government ever since. Arguably, however, the blame lies with the Constitution, which gave the US government its greatest power—the power to tax.

This article was published by the MISES Institute

How was the Whiskey Rebellion a direct result of a tax on imports? The Whiskey tax on domestic production as not passed in 1789. Please remove the extraneous reference to the Whiskey Rebellion.