Did Coup Leaders Seek Legitimacy By Addressing The UN? – OpEd

By Thalif Deen and IDN

The recent military coup in Myanmar and an attempted palace coup in Jordan harks back to the days when insurrections by armed forces came along a veritable assembly line—particularly in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia.

And at least one political leader—a former Prime Minister of Thailand—was ousted from power when he was at the United Nations to address the General Assembly. After he finished his address, he was homeless and had no country to go to, and sought political asylum in a Middle Eastern country.

And that country was known to welcome several world leaders on the run—even as a newspaper cartoon caricatured an EXPRESS lane at its arrival lounge in the airport terminal, with a sign reading: “FOR VIPs—AND OUSTED WORLD LEADERS ONLY.”

Meanwhile, the dethroning of a Prime Minister during a UN session prompted one official to sarcastically advise all visiting world leaders to bring—along with their bag and baggage—their army, navy and air force chiefs as part of the country’s UN delegation in order to avoid potential military coups back home.

Regrettably, military coups also come with heavy losses in human lives. In Myanmar, the UN Country Team has remained “deeply concerned over the continued loss of lives following the military takeover of the government on 1 February”.

As of last week, at least 224 civilians have been killed at the hands of security forces, including while in custody. But the real figure could be over 250, as hundreds more, including women and children, have been injured, according to the UN Human Rights Office.

Besides Myanmar, there were two attempted bloodless coups in February this year—in Haiti and Armenia. But they never got off the ground.

A newly released book* on the United Nations recounts the late Kofi Annan as the only UN Secretary-General (1997-2006) who challenged the General Assembly, urging member states to deny the UN podium to political leaders who come to power by undemocratic means or via military coups.

As one senior UN official put it: “Were military leaders seeking legitimacy by addressing the General Assembly?”

In 2004, when the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor to the present African Union (AU), barred coup leaders from participating in African summits, Annan singled out that landmark decision as a future model to punish military dictators worldwide.

Annan went one step further and said he was hopeful that one day the General Assembly, the highest policy making body in the Organization, would follow in the footsteps of the OAU, and bar leaders of military governments from addressing the General Assembly.

Annan’s proposal was a historic first. But it never came to pass in an institution where member states, not the Secretary-General, rule the Organization. However, any such move could also come back to haunt member states if, one day, they find themselves representing a country headed by a military leader.

The outspoken Annan, a national of Ghana, also said that “billions of dollars of public funds continue to be stashed away by some African leaders — even while roads are crumbling, health systems are failing, school children have neither books nor desks nor teachers, and phones do not work.” He also lashed out at African leaders who overthrow democratic regimes to grab power by military means.

Needless to say, the UN does not make any distinctions between “benevolent dictators” and “ruthless dictators.” But as an international institution preaching multiparty democracy and free elections, it still condones military leaders by offering them a platform to speak — while wining and dining with them during the annual General Assembly sessions.

Although Yasser Arafat, the leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), addressed the UN, some of the world’s most controversial authoritarian leaders, including Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, Syria’s Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar al-Assad, and North Korea’s Kim il Sung and his grandson Kim Jong-un, never made it to the UN.

When former Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir, accused of war crimes, was refused a US visa to attend the high-level segment of the General Assembly sessions back in September 2013, a Sudanese delegate told the UN’s Legal Committee that “the democratically-elected president of Sudan had been deprived of the opportunity to participate in the General Assembly because the host country, the United States, had denied him a visa, in violation of the UN-U.S. Headquarters Agreement.”

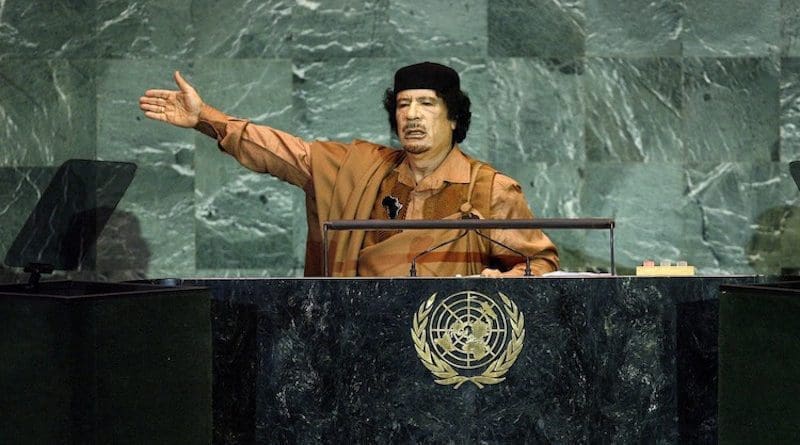

Meanwhile, some of the military leaders who addressed the UN included Fidel Castro of Cuba, Col Muammar el-Qaddafi of Libya, Amadou Toure of Mali (who assumed power following a coup in 1991 but later served as a democratically elected President), and Jerry Rawlings of Ghana (who seized power in 1979, executed former heads of state but later served as a civilian president voted into power in democratic elections).

As the International Herald Tribune (IHT) pointed out years ago, Rawlings was “Africa’s first former military leader to allow voters to choose his successor in a multi-party election”.

The erratic Qaddafi, made a historic visit to the UN in September 2009. In its report, the London Guardian said he “grabbed his 15 minutes of fame at the UN building in New York and ran with it. He ran with it so hard he stretched it to an hour and 40 minutes, six times longer than his allotted slot, to the dismay of UN organizers”.

Qaddafi fully lived up to his reputation for eccentricity, bloody-mindedness and extreme verbiage, said the Guardian, as he tore up a copy of the UN charter in front of startled delegates, accused the Security Council of being an al-Qaida like terrorist body, called for (US President) George Bush and (UK Prime Minister) Tony Blair to be put on trial for the Iraq war, demanded $7.7 trillion in compensation for the ravages of colonialism on Africa, and wondered whether swine flu was a biological weapon created in a military laboratory.

In October 2020, the New York Times reported that at least 10 African civilian leaders refused to step down from power and instead changed their constitutions to serve a third or fourth term -– or serve for life.

These leaders included Presidents of Guinea (running for a third term), Cote d’Ivoire, Uganda, Benin, Burkina Faso, Central African Republic, Ghana and Seychelles, among others. The only country where the incumbent was stepping down was Niger.

Condemning all military coups, the Times quoted Umaro Sissoco Embalo, the president of Guinea-Bissau, as saying: “Third terms also count as coups”.

Last week, the killing of Idriss Deby, the President of Chad, described as “one of Africa’s most enduring autocrats”, has resulted in the installation of his 37-year-old son Mahamat Idriss Deby as the new President. But political opponents are describing it as a “coup d’etat” because the country’s constitution dictates the president of the National Assembly should be the interim leader until elections are held, according to a report in the New York Times, April 24.

According to the Times, the governments of several Southeast Asian countries have the hallmarks of authoritarian military governments.

The leader of Thailand’s last coup, Prayuth Chan-o-cha, a former chief of the Thai army, is still the Prime Minister of the politically volatile country. In Cambodia, Hun Sen, described as Asia’s longest-ruling leader, has set up a political dynasty, and in the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte has presided over thousands of extra-judicial killings.

The US has officially determined that China’s authoritarian regime is committing genocide against Uyghur Muslims and other ethnic and religious minority groups.

One longstanding authoritarian President of a Southeast Asian nation, known to rig elections, was reportedly quoted as saying: “I promised I will give you the right to vote. But I did not say anything about counting those votes.”

Meanwhile, Russian President Vladimir Putin has signed a law paving the way for him to run for two more presidential terms extending his rule until 2036, according to a report in Cable News Network (CNN).

In early April, the Lower House of the Somali Parliament extended the President’s term for two more years. The Upper Chamber of the Somali Parliament says this is illegal and wants the international community to intervene.

Asked for his comments, UN Spokesperson Stephane Dujarric told reporters last week: “We’ve seen these latest developments. I can tell you they are very concerning to us, what is going on in Somalia. We’re assessing what exactly has been decided and the impact and so on.”

And on the recent meeting of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) on Myanmar, he said: “ASEAN has a very important role to play in helping us achieve the goal that we all want— which is a return to civilian rule in Myanmar”

Thalif Deen, Senior Editor & Director, UN Bureau, Inter Press Service (IPS) news agency has been covering the United Nations since the late 1970s. Beginning with the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992, he has covered virtually every major U.N. conference: on population, human rights, the environment, sustainable development, food security, humanitarian aid, arms control and nuclear disarmament.

*This article contains extracts from a newly-released book on the United Nations titled “No Comment – and Don’t Quote Me on That.” Authored by Thalif Deen, a one-time UN staffer, a some-time Sri Lankan diplomat and a longtime UN journalist, the 220-page book is peppered with scores of anecdotes– from the serious to the hilarious– and is available on Amazon worldwide and at the Vijitha Yapa bookshop in Sri Lanka. The links follow: https://www.rodericgrigson.com/no-comment-by-thalif-deen/https://www.vijithayapa.com/