Economic Nationalism Takes Center Stage In 2020 US Election – Analysis

By Observer Research Foundation

By Kashish Parpiani

Ahead of the 1992 election, President George H W Bush enjoyed an 89 percent approval rating following the success of Operation Desert Storm. Expected to trounce US elections’ long-standing dictum over the limited electoral relevance of foreign policy wins, later that year however, Bush lost to Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton. In focusing on the 1990-91 economic recession instead, Clinton had promised to “Make America Great Again!”

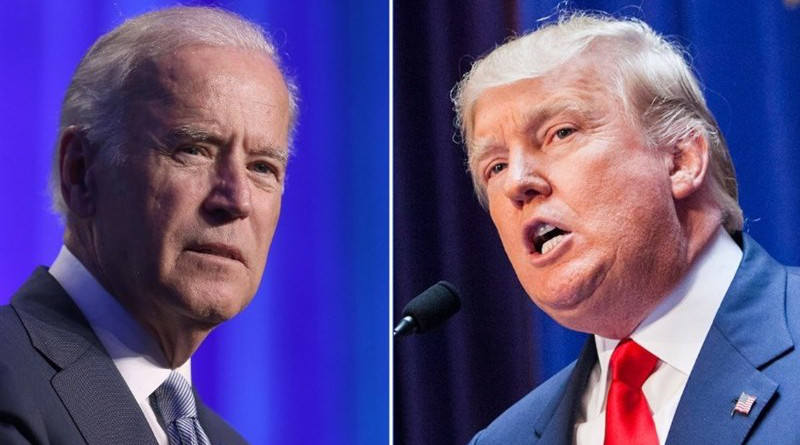

In 2016, Donald Trump adopted the lessons of 1992 beyond his repurposing of the MAGA clarion on red baseball caps. He mounted a conservative nationalist movement centred on promising an “American economic revival”. Now, in seeking a renewal of his mandate, Trump has adopted varied talking points — like rallying against the “invisible China virus” and the “new far-left fascism”. His focus on the economy however, continues.

In touting piecemeal gains such as the stock market having “its best quarter in more than 20 years” (mostly due to the largest-ever US stimulus package passed in response to the coronavirus pandemic) or the recent jobs report as per which the US added 4.8 million jobs in June (hardly offsetting the 22.2 million jobs lost this year), Trump has made a case against the Democratic nominee and former Vice President Joe Biden. Deriding his plans to raise taxes, the Trump campaign has warned that Biden will kill the “Great American Comeback”.

This seems to have worked as a recent poll revealed that Trump has maintained the backing of “a majority of voters on the economy, with 54% approving of his handling of the matter, a record high in the poll” — even as his overall rating against Biden dropped by 11 percentage points. This has prompted Biden to mirror Trump’s message on overseeing the revival of the US economy.

Biden’s Trumpian move

In a speech from his home-state of Pennsylvania, Biden unveiled his own populist vision for the economy. With his new slogan (“Build Back Better”), he advocated for domestic investments to “spur domestic innovation, reduce the reliance on foreign manufacturing and create five million additional American manufacturing and innovation jobs.”

Echoing the economic nationalism of Trump’s 2017 executive order on ‘Buy American and Hire American’, Biden said: “When the federal government spends taxpayers’ money, we should use it to buy American products and support American jobs”. Reported as Biden’s ‘Buy American’ plan, it proposes an US$ 300 billion investment in “Research and Development and Breakthrough Technologies — from electric vehicle technology to lightweight materials to 5G and artificial intelligence — to unleash high-quality job creation in high-value manufacturing and technology.” And another US$ 400 billion as federal investment to “power new demand for American products, materials, and services and ensure that they are shipped on US-flagged cargo carriers.”

Speaking at a metalworks factory in the electorally-crucial state which Trump won by 0.7 percentage points in 2016, Biden’s target audience was undoubtedly the blue-collar voter. Addressing their economic woes, Biden even alleged Trump to have failed in bringing back manufacturing jobs, and deemed him to be “singularly focused on the stock market, the Dow and NASDAQ. Not you. Not your families”.

In 2016, Trump had galvanised the working-class whites for instance, by attributing their economic hardships to the hollowing-out of America’s industrial base. Trump rallied against the destruction — in terms of loss in manufacturing jobs and increase in immigrant labour, wrought by incessant globalisation due to the American political establishment’s pursuit of free trade. This was pivotal in catapulting Trump to the White House, with Hillary Clinton — accused of being the embodiment of American internationalism, failing to win “more than about a third of the white working-class vote” in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin. Hence, upon assuming office, the Trump administration’s ‘America First’ vision deemed the recalibration of trading relationships as a top foreign policy priority.

In a sign of Trump now replicating his 2016 approach, the Trump administration’s chief trade negotiator recently penned a series of articles. Touting the efficacy of exacting “fair and reciprocal” trade deals via employing punitive measures against friends and foes alike, US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer argued: “From January 2017 to January 2020, 500,000 new manufacturing jobs were created and real wages for manufacturing workers rose by 2.5 percent, compared to a decline of 0.6 percent from January 2009 to January 2017.”

Whereas, Biden’s ‘Buy American’ plan aims to arrest a decline in American manufacturing jobs through rigorous domestic investment. He has even pledged to “not sign any new trade deal until we have made major investments in our workers and infrastructure.”

Beyond binaries

Both candidates have drawn on economic nationalism also in view of it being conducive towards targeting their opponent’s political vulnerabilities. For instance, the Trump campaign has been highlighting Biden’s past-record on free trade.

As his 2002 Senate vote to authorise the Iraq War continues to impede Biden’s attempt to project himself as being level-headed on foreign policy, his 1993 vote for the North American Free Trade Agreement (NATFA) often derails his attempt to connect with blue-collar workers. Reportedly, NAFTA overtime spurred the loss of about 700,000 jobs as manufacturers moved operations to Mexico. The potency of highlighting Biden’s NAFTA vote stands exacerbated with progressives from the Democratic party also often rallying against his track-record on free trade being detrimental to workers.

In addition, as vice president, Biden was a vocal supporter of the Obama administration’s Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). Whereas, three days after he assumed office, Trump withdrew from the TPP and hailed the move as a “great thing for the American worker.” His administration had criticised the agreement’s ‘rules of origin’ clauses which would have been exploited by countries like China to move portions of their production to TPP nations — to gain duty-free treatment, and eventually further flood the US market.

For Biden, the scope for targeting Trump on trade is limited due to his administration’s successful negotiation of limited deals with South Korea, Japan, China, and replacement of NAFTA with the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

However, his administration’s approach of engaging in trade wars has been controversial. Trade war with China for instance, cost US businesses US$ 50 billion in additional duties, agricultural exports to China dropped from US$ 19.5 billion in 2017 to US$ 9 billion in 2018, and bankruptcies amongst farmers increased by 20 percent in 2019. To mitigate the damage, the Trump administration announced taxpayer-funded payments worth US$ 26 billion for farmers. In highlighting such ramifications, Biden has construed the correction of trading arrangements as a matter of putting the cart before the horse, if not predicated with rigorous domestic investments.

Beyond these political and electoral considerations informing the candidates’ invocation of economic nationalism, there is evidence that the debate over revitalising American manufacturing goes beyond the binary of which candidate’s approach is better.

In 2016, the United Auto Workers (UAW) union endorsed Hillary Clinton, but “a higher-than-normal 32%” of its members voted for Trump and were crucial in flipping Michigan from blue to red. Once in office, as Trump repeatedly deferred on imposing tariffs on automobile imports, UAW leaders conveyed that “targeted” tariffs would be a good idea. Similarly, after endorsing Clinton in 2016 (and now Biden for 2020), the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organisations (AFL-CIO) supported Trump’s Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminium, and even backed the USMCA — as their first endorsement of a trade agreement since 2001.

Hence, the 2020 US presidential election will oversee the further consolidation of economic nationalism in American worldview.