To Withdraw Or Not: South Korea’s Strategic Calculus And The GSOMIA – Analysis

By IPCS

By Dr. Sandip Kumar Mishra*

On August 24, the General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), an intelligence-sharing agreement between South Korea and Japan, was automatically extended for another year.

Article 21(3) of the agreement states: “This agreement shall remain in force for a period of one year and shall be automatically extended annually thereafter unless either Party notifies the other in wiring through the diplomatic channel ninety days in advance of its intention to terminate the Agreement.”

Unlike last year, when South Korea gave a ninety-day notice for withdrawal from the agreement, this year’s was silently extended. In fact, South Korea’s 2019 withdrawal notice was suspended on 22 November, on the basis of having bridged differences on certain trade issues with Japan. Although Seoul has since reiterated its right to withdraw when appropriate, it has mellowed its stand more recently. The question is: Why has it neither withdrawn from the agreement, nor recalled its withdrawal notice?

Seoul is dissatisfied with Tokyo’s response to the South Korean court order of October 2018, which ordered Japanese businesses to compensate those forced into labour in the colonial period. This resulted in Japan removing South Korea from the ‘white list’, after which several Japanese exports to South Korean companies became eligible for prior government approval. South Korea alleged that Japan had chosen to link a historic dispute with current bilateral trade and other exchanges, which it felt needed to be dealt with strongly.

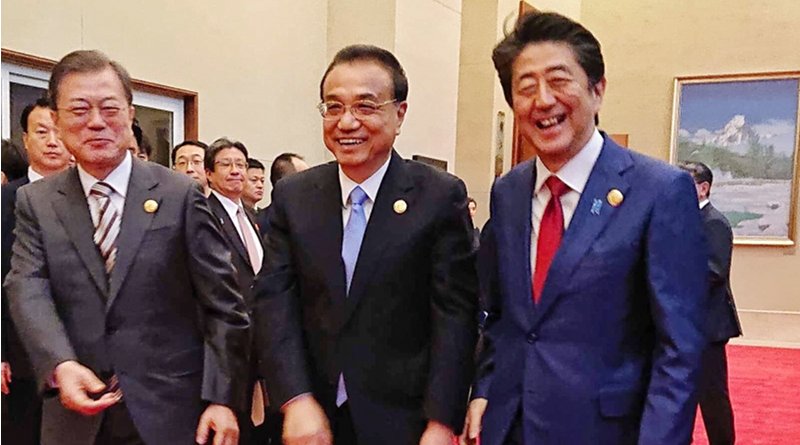

In actuality, South Korea and Japan have been drifting apart since 2017, coinciding with the beginning of Moon Jae-in’s tenure as president. President Moon questioned the “final and irreversible” resolution of the ‘comfort women’ issue between the two countries, which had been addressed in a December 2015 bilateral agreement. The Japanese government led by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was quite unhappy with this new approach.

Fast-forwarding to 2019, Seoul retaliated strongly to its removal from the ‘white list’ through a reciprocal measure aimed at Tokyo, following which it sent notice regarding withdrawal from the GSOMIA. It justified its actions on four grounds. One, it felt the agreement on ‘comfort women’ was arrived at without wider consultations and without an expression of genuine Japanese remorse. Two, the South Korean government had no role in the court order regarding forced labour. Moon Jae-in had proposed a joint bilateral fund to better resolve the issue.

Three, the GSOMIA signed between the two countries in 2016 had yet to deliver significant results on intelligence-sharing because of the bilateral trust deficit. Further, both South Korea and Japan share intelligence with the US along parallel tracks, which would reach them anyway, albeit more circuitously. Fourth, Seoul considered it important to demonstrate a tougher stand as a means to signal both Tokyo and Washington of having its interests and sensitivities paid greater respect.

Having said that, South Korea is also aware that it must not go overboard and rock the boat completely. Walking out of the agreement may not serve South Korea’s interests. Its restraint in November 2019 and now is based on a number of calculations. Seoul cannot overlook the US role in pacifying both South Korea and Japan. A withdrawal from the agreement might reflect negatively in its relationship with the US, which is particularly important given that Moon Jae-in seeks President Donald Trump’s cooperation in dealing with North Korea. Avoiding any negative escalation in Japan-South Korea relations with the US presidential elections around the corner would be part of the same calculation.

Japan is one of South Korea’s most important economic partners. Therefore, to send strong signals through strategic posturing without threatening existing and potential cooperation avenues is crucial. The strained bilateral equation has already contributed to many businesses in both countries suffering, which must be minimised. Finally, with Seoul and Tokyo involved in health and economic recovery in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, it would be unwise to open up another front.

Overall, the GSOMIA extension is a good sign. This time can used to bridge gaps in bilateral positions and perspectives. However, it cannot be done effectively unless a series of confidence-building measures are agreed upon and executed. For this, both countries must be flexible. The Moon Jae-in administration has extended a few olive branches in the past year-and-a-half, but Shinzo Abe is apparently less willing. In a changing regional context, South Korea and Japan must devise a way to transcend differences and work together for a better collective future.

*Dr Sandip Kumar Mishra is Associate Professor, Centre for East Asian Studies, SIS, JNU, and Visiting Fellow, IPCS.