Politics In Nicaragua – Analysis

By Richard Purcell

On November 7, Nicaragua will hold its next presidential election. It is widely expected that the nation’s sitting president, Daniel Ortega, will prevail in overwhelming fashion. Ortega, who faces no serious challengers, assumed the presidency in 2007 following an election in which he received only 38 percent of the vote. As the election date approaches, it is worth looking back on Nicaragua’s political evolution in recent decades and Daniel Ortega’s role in it.

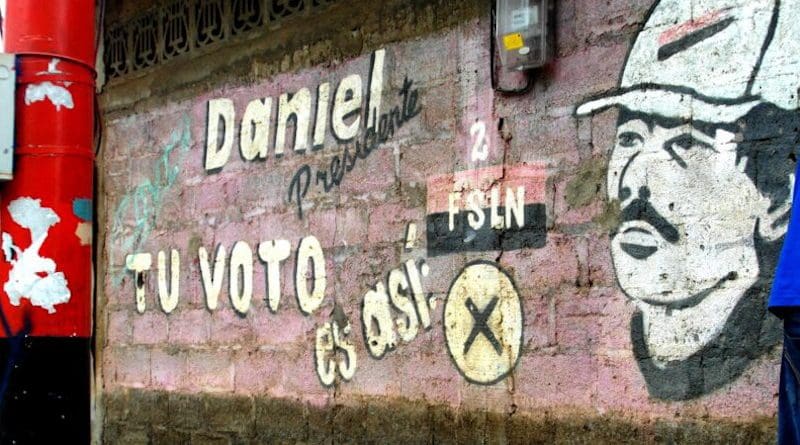

Ortega has been an influential figure in Nicaraguan politics throughout the modern era. He was one of the original nine comandantes of the leftist Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) that overthrew the US-backed Somoza family dictatorship in 1979. He emerged as the nation’s president in 1985 following an election that, while judged to have been free and fair by international observers, was boycotted by anti-Sandinista groups at the urging of the United States.

Ortega’s first stint as president took place while the country was under US sanctions and fighting a civil war against US-backed Contra rebels. In 1989, Ortega agreed as part of regional peace negotiations to hold national elections in February 1990 that would involve participation of opposition parties and would be monitored by international election observers. His main opponent, Violeta Chamorro, the widow of a prominent newspaper editor and critic of the Somoza government, who was assassinated in 1978, was supported by a diverse array of anti-Sandinista groups on the political right. Ortega and many others believed that he was likely to win, but the election resulted in a decisive Chamorro victory, with Ortega garnering only 41 percent of the vote to her 55.

Upon taking office, Chamorro felt she had no choice but to adopt a conciliatory approach in her dealings with the FSLN. Despite their defeat, the Sandinistas remained powerful. They still controlled much of the bureaucracy as well as the civil service unions, and Ortega remained a member of the legislature and a top figure within the party. These circumstances permitted him to fulfill the vow he made in his concession speech to “govern from below” upon stepping down from the presidency. His ability to initiate nationwide labor strikes, street protests, and mob violence allowed him to paralyze the nation at will. This provided Ortega with enormous leverage over the Chamorro administration, forcing it to often cede to Sandinista demands on a variety of matters, even though Ortega was no longer president and the FSLN held only 39 of the 92 seats in the National Assembly. Chamorro’s willingness to work with the Sandinistas eventually led her supporters in the National Assembly to abandon her.

However, the Sandinistas faced deep divisions within their own ranks after the 1990 election defeat. The FSLN held a National Congress in July 1991 to try to resolve some of its internal fissures, but unity proved elusive. Pragmatists called for a “renovation” of the party that would allow it to evolve into a modern social democratic party. The renovators were led by Sergio Ramirez, the vice president under Ortega during the late 1980s, who emphasized the value of compromise and the need to build coalitions with other political groups. Ortega led the hardliners, who called themselves the Izquierda Democratica (ID), or Democratic Left (DL). It was this faction that “led from below” during the Chamorro years through strikes, protests, and mob violence.

Ortega ran for president again in the 1996 election to choose Chamorro’s successor. (Constitutional changes enacted in 1995 prohibited presidents from serving consecutive terms, and the presidential term was shortened from six years to five.) His main opponent was Arnoldo Alemán, the mayor of Managua. Alemán ran as the candidate of the Liberal Alliance, a coalition of political factions on the right who opposed the Sandinistas. Together, the FSLN and the Liberals dominated Nicaraguan politics during this period.

During the campaign, Alemán argued that, if elected, Ortega would return the country to the difficult days of the 1980s. Ortega sought to allay such fears. Despite his having driven reformist elements out of the FSLN, he abandoned much of the leftist Sandinista ideology he had championed during his earlier term as president. Instead, he portrayed himself as a moderate who was “an agent of conciliation.” He publicly embraced capitalism and stated his desire for a constructive relationship with the United States. Ultimately, however, Alemán won the election with 51 percent of the vote. Ortega received 38 percent, a three point drop from the 41 percent he won in 1990.

The most pronounced feature of Alemán’s presidency was its corruption. During his term, he allegedly stole upward of $100 million from state coffers and used it for his personal enrichment. This included $1.8 million in charges to government-paid American Express cards for extravagant personal expenses, including jewelry, rugs, stays in lavish hotels, and a honeymoon to Italy. In a nation where the average annual income was $430 a year, the news that the president had engaged in such gross malfeasance was met with widespread public anger.

As president, Alemán served as a member of the Constitutionalist Liberal Party (PLC), which by the late 1990s had emerged as the primary political vehicle for the nation’s Liberals, supplanting the earlier Liberal Alliance. In 1999, he reached an agreement with Ortega that became known as ‘el pacto’ (the pact), an arrangement intended to entrench the PLC and FSLN as the central players in Nicaraguan political life.

Implementation of the pact began in January 2000, when the FSLN and PLC blocs in the National Assembly enacted a set of “reforms” that rewrote Nicaragua’s constitution to their mutual benefit. One provision granted sitting presidents immunity from arrest and prosecution. Another change gave the president automatic membership in the National Assembly upon leaving office, a position which, again, conferred legal immunity on its holder. These changes were primarily intended to shield Alemán from prosecution on corruption charges.

The pact also altered the rules governing presidential elections. Since 1995, the top vote getter of the presidential race had to receive at least 45 percent of the vote in order to avoid a runoff. In 2000, this was threshold was lowered to 40 percent. In addition, the new provision made it possible to win with as little as 35 percent if the victor’s vote count exceeded that of the next candidate by at leave five percent. These changes were clearly made to benefit Ortega, who seemed to have an electoral ceiling of around 40 percent.

Finally, the pact gave the FSLN and PLC control over government institutions that were intended to be independent from the executive and legislative branches. The size of the Supreme Electoral Council, which was charged with ensuring the integrity of Nicaraguan elections, was increased from five to seven members, with the FSLN and PLC able to select three each. Similarly, the Supreme Court of Justice was expanded from twelve to sixteen judges, half of whom would be chosen by each party. And the Comptroller’s office, which had been led by one individual, was now to be overseen by five officials – three named by the PLC and two named by the FSLN.

Undaunted by his previous defeats, Ortega ran for president again in 2001. He lost this time to Enrique Bolaños, Alemán’s vice president, by a margin of 56 to 43. Because of the constitutional changes enacted as part of the pact, Alemán automatically became a member of the National Assembly after stepping down from the presidency. The PLC caucus, which had won 52 of the Assembly’s 92 seats, selected him to serve as its legislative leader.

Upon taking office, Bolaños made rooting out government corruption his top priority and immediately launched an investigation into Alemán’s corrupt activities. His decision to turn on his predecessor and fellow PLC member came as a surprise to many, but most Nicaraguans supported his efforts, as did the U.S. and much of the international community.

Politically, however, Bolaños’s anti-corruption drive was a disaster. It led to a fissure among Nicaragua’s Liberals that was to have far-reaching consequences. PLC members of the National Assembly remained loyal to Alemán, and they refused to heed Bolaños’s call for the legislature to strip him of his immunity. Bolaños quickly found himself a president without a party, putting him in the awkward position of having to ally himself at times with the Ortega-controlled Sandinista minority.

In September 2002, a small number of pro-Bolaños legislators defected from the PLC. Combined with the 38 votes from the FSLN bloc, this was enough to give Bolaños the legislative majority he needed to remove Alemán’s immunity. After the vote was taken, Alemán was arrested and charged with multiple counts of corruption. He was convicted in December 2003 and was sentenced to 20 years of house arrest at his palatial, 20-acre ranch. Four years later, a court rescinded his house arrest on the condition that he not leave the country.

The rest of Bolaños’s administration was troubled. In 2003 he ended his working relationship with Ortega in the face of U.S. pressure. This action revitalized the pact between the FSLN and the PLC. In 2004, the two parties used their combined majority in the National Assembly to enact additional constitutional changes that drastically curtailed the president’s authority, leaving him little more than a national figurehead. Bolaños refused to recognize the validity of the amendments, and a constitutional standoff ensued, paralyzing the government. The Organization of American States (OAS) mediated negotiations between Bolaños and Ortega, and in October 2005 the two agreed that the constitutional changes would not take effect until after the next president took office.

Ortega’s return to power

The 2006 presidential election proved to be a turning point, both for Ortega and the nation as a whole. He had run for president in 1990, 1996, and 2001, and lost each time. In each election, his share of the vote total hovered around 40 percent. Determined to return to power, he ran again in 2006 and this time was victorious. However, he did not win by expanding his popularity among Nicaraguan voters. He garnered only 38 percent of the vote, a five-point decline from his 2001 showing.

Ortega won by exploiting the split among Nicaragua’s Liberals. In the 2006 election, the PLC – which still remained loyal to Alemán – nominated José Rizo as its presidential candidate. But a dissident faction of anti-Alemán Liberals broke away from the PLC and formed a new party, the Nicaraguan Liberal Alliance (ALN), led by Eduardo Montealegre, Alemán’s former foreign minister. In the election, Rizo won 27 percent of the votes cast while Montealegre won 28 percent.

Had Nicaragua’s Liberals been able to unite behind a single candidate, they would have prevailed. Even if that had not happened, Montealegre and Ortega, the two top vote getters, would have faced one another in a runoff were it not for the revisions to Nicaraguan electoral law enacted in 2000 as part of the pact. Had that occurred, Montealegre would almost certainly have won. The lowered threshold for victory allowed Ortega to win outright in the face of a divided opposition.

Upon returning to the presidency in 2007, Ortega began taking steps to expand his authority at the expense of Nicaragua’s democratic institutions. In his first month in office, Ortega persuaded the National Assembly to not only reverse the constitutional changes passed in 2004 but to also enact new laws strengthening the president’s authority relative to that of the legislature.

Later that year, Ortega established Citizens Power Councils in communities throughout the country. These were ostensibly intended to empower local communities and give them greater say on how anti-poverty aid was spent. In reality, the councils were meant to cement the FSLN’s control. They were controlled by Sandinistas and were used for patronage purposes, allocating largesse to party supporters.

The funds that were doled out by the councils came from economic aid from Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela in the form of cheap oil. Venezuelan assistance began flowing to Nicaragua not long after Ortega’s return to power. From 2008 through 2015, Chavez and his successor, Nicolás Maduro, directed over $3.6 billion in aid to an account that was allegedly controlled solely by Ortega. These funds were apparently not part of Nicaragua’s national budget and were therefore not subject to oversight by the National Assembly or any other governmental body.

Ortega’s wife, Rosario Murillo, emerged a as a powerful figure within the government. Although they did not marry until 2005, Ortega and Murillo have been together since before the 1979 revolution. A woman of considerable political ambition in her own right, she stood by Ortega in 1998 when her daughter accused him of molesting her as a child. She ran Ortega’s 2006 presidential campaign. After he took office, she oversaw the management of the Citizens Power Councils and also served as her husband’s communications director.

The regime began cracking down on civil society groups, particularly those that advocated for women, political opponents, and independent journalists. In July 2008, thousands of demonstrators took to the streets to protest Ortega’s recent decision to outlaw two small opposition parties as well rising food and fuel prices. He responded that any attempt to remove him from power would be met with “the steel of war.”

As the 2008 municipal elections approached, the two main Liberal factions, the ALN and the PLC, attempted to resolve their differences so that they could produce a unified slate of anti-Ortega candidates. After the voting took place in November, the Supreme Electoral Council reported that the FSLN had won 94 of the nation’s 146 municipalities. However, many observers alleged widespread voter fraud. Montealegre, who had run for mayor in Managua, claimed that the elections had been rigged by the Sandinistas, pointing to the regime’s refusal to provide accreditation to independent election-monitoring organizations for the first time since 1990. The Catholic Church and Nicaragua’s two main business associations called for an independent investigation into the matter while the U.S. and the European Union suspended $150 million in economic aid.

A year later, Ortega petitioned the Supreme Court to overturn the nation’s constitutional ban on presidents serving consecutive terms. The Sandinista members, acting alone, ruled in his favor, stating that the prohibition violated Ortega’s human rights. In early February of 2011, the FSLN officially renominated Ortega as its candidate for the fall presidential election.

Ortega’s 2011 reelection and aftermath

If the 2006 election marked the onset of Ortega’s authoritarian rule, the 2011 election represented an important step in its consolidation. Pre-election polling suggested that Ortega was likely to win with a plurality of the vote. This finding was consistent with his performances in previous elections and an October 2010 poll indicating he had an overall approval rating of 45 percent.

As was the case in 2006, Nicaragua’s Liberals were in a state of disarray. Alemán, whose conviction on corruption charges had been overturned in 2009, ran again as the PLC candidate, though his party was fading in significance. Fabio Gadea, a 79-year-old owner of a Nicaraguan radio station, served as the candidate of the Independent Liberal Party (PLI), a hastily assembled coalition composed of Liberals who had supported Montealegre in 2006 and ex-Sandinistas who opposed Ortega.

According to the official tabulation announced by the Supreme Electoral Council, Ortega won with 63 percent of the votes cast. Gadea received 31 percent, while Alemán garnered only six. In the National Assembly, the FSLN won 62 seats, giving it a supermajority that would allow it to pass legislation without needing to compromise with opposition lawmakers.

A post-election report published by the Carter Center, a human rights NGO founded by former US president Jimmy Carter, described the 2011 election as “a watershed event, realigning political power [and] dealing a debilitating blow to Nicaraguan democracy.” While there was no obvious evidence of electoral fraud, the 2011 results were challenged by both international and domestic observers, and none of the opposition candidates recognized the validity of the reported outcomes. One objection was that the 2009 Supreme Court ruling allowing Ortega to run for reelection had been unlawful. In addition, the regime had restricted independent election monitors’ access to voting centers, and there were widespread reports of voting irregularities. The Supreme Electoral Council, supposedly an independent and unbiased arm of the government, was also widely understood to be controlled by the Sandinistas, and it carried out its operations with very little transparency.

Following Ortega’s reelection, Murillo began to take over more and more of the day-to-day aspects of governance, presiding over cabinet meetings and eventually assuming the role of de facto foreign minister. For many years now, she has also served as the public face of the regime, addressing the nation on national television on a daily basis. In her TV appearances, Murillo discusses a wide variety of topics, ranging from government anti-poverty programs to the importance of Nicaraguans treating one another with kindness. She frequently espouses her spiritual beliefs, which are a combination Catholicism and New Age mysticism.

The Ortega-Murillo government has also carried out a mostly successful campaign to silence independent news outlets in Nicaragua through acquisition or intimidation. By 2014, seven of the nation’s eight national television stations were controlled by a member of the ruling family or a close political ally. Independent journalists have been denied access to government officials, including the ruling couple, since Ortega took office in 2007.

In January 2014, the FSLN-controlled National Assembly approved further amendments to the constitution at Ortega’s behest. The ban on consecutive presidential terms was completely eliminated, and runoff elections were abolished. All that was necessary to win the presidency was a plurality of the vote. Additionally, the powers of the executive branch were further enhanced, allowing Ortega to rule by decree and unilaterally select military and police commanders.

The stage was thus set for the upheavals of 2018, which will be covered in the next article in this series.

This article was published by Geopolitical Monitor.com