The Persecution Of Christians In The Middle East – OpEd

At the international level, any progress toward ensuring the protection of religious freedom and reducing discrimination against and persecution of religious minorities has been hampered by the failure of the United Nations.

By Dr. Alon Ben-Meir*

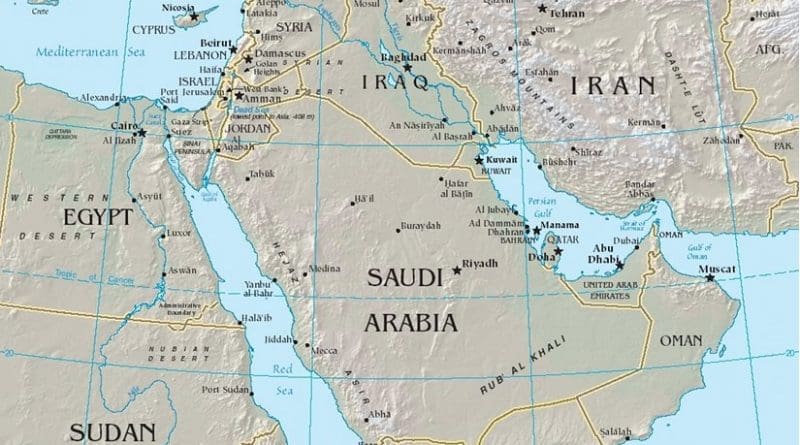

Although Christians have lived in the Middle East – the birthplace of Christianity – for nearly two thousand years, as a result of years of persecution and discrimination, especially in the past 15 years, they now constitute no more than 3-4% of the region’s population, down from 20% a century ago. Christians are not the only minority being discriminated against in this region, but their plight is more visible in many places, beyond what has been experienced by Yazidis, Kurds, Druze, and others. Unfortunately, given the turmoil in the Middle East and the rise of Islamic extremism, with few exceptions Christians and other minorities may no longer be able to live in harmony with their largely Muslim neighbors.

There are several factors contributing to the persecution of religious minorities in the Middle East. Although sectarian conflicts in the region are not new, the 2003 Iraq War and the Arab Spring unleashed a new torrent of violence between Sunnis and Shias and against other religious minorities.

The rise of Islamic extremism has been a singular driving force in the plight of religious minorities, fueling a growing desire to resort to religion as a palliative. The resurfacing of religious division vis-à-vis the Sunni-Shia conflict, and between different Sunni sects, is creating a societal mindset that posits other religious groups as ‘the enemy.’ Groups like al-Qaeda and ISIS exploit this intolerance of religious and inter-religious out-groups, with the latter taking such fanaticism to new and barbaric heights.

In addition, the wanton persecution of religious minorities is compounded by the threat of radicalization, which threatens social cohesion and combines religious doctrine with fanatical violence. As Blaise Pascal aptly put it, “Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction.”

The prevailing frustration, pain, and agony in the region as a result of socio-economic despondency adds further impetus to the spike in discrimination—when governments fail to step in and mitigate the situation, there is a tendency to find a ‘sacrificial lamb’ to blame one’s ills on.

The fact that there is rampant unemployment, limited opportunities for higher education, and that tens of millions of Muslims live in poverty all fosters a sense of resentment against other minorities.

Arab nationalism is another major factor that was reinvigorated in the wake of Arab Spring, and as a result, discrimination against Christians was sharpened in certain countries, including Iraq and Saudi Arabia. The growing influence of Islam into the state framework created cleavages between religious minority groups and the majority.

The prevalence of blasphemy laws throughout the region add another complex layer to religious discrimination. These laws, which are frequently abused to settle personal scores, often carry with them a mandatory death sentence. Allegations of blasphemy are often presented with no evidence, because to reproduce the evidence would be to reproduce the blasphemy.

Finally, a widely-held perception in the Middle East today is that many of the region’s socioeconomic problems are attributable to the legacy of the post-World War I and II colonial eras and the exploitive regimes of those times. Though many of the newly independent states immediately turned to autocratic rule, the pre-existing state structures were largely kept in place to the relief of religious minorities.

The Arab Spring, though, put this political order to the test—the demand for democratization made many religious minorities uneasy, worried that the legal protections carried over from the Ottoman era would fall to the wayside.

There are several remedies and countermeasures that must be taken to mitigate religious discrimination. To begin with, a renewed and concerted push is necessary at the political level, led by the world’s major powers to end many of the raging regional conflicts. Needless to say, this is easier said than done, but then regardless of how extremely intractable many of these conflicts are, no one should expect that persecution of minorities would be eliminated or be appreciably minimized unless these conflicts come to an end.

Ending regional conflicts, including a resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, would substantially reduce tensions in much of the region and bring Israel closer to the Sunni Arab world, while depriving extremist groups such as Hamas and Hezbollah of their raison d’etre.

A solution to the Syrian conflict would stabilize what is left of the fractious nation and could help improve the status of the remaining Christian community in particular, which has seen many of its holy sites defaced or completely destroyed at the behest of radical Islamist militias such as ISIS.

The Sunni-Shiite conflict, spearheaded by Saudi Arabia and Iran respectively, is another conflict that feeds into the frenzy of extremism and must also be mitigated, even though it may take years if not decades.

Preventive diplomacy is critically important any time there is a sign that acts of persecution might take place, or there appears to be a gradual emergence of an environment that could lead to persecution—measures taken by the West, and particularly the United States, in a timely fashion would prevent such developments from occurring.

Furthermore, in responding quickly to atrocities against religious minorities, outside powers need to interject themselves more forcefully before conflicts spiral out of control. There is evidence that suggests timely intervention in Syria, however limited in scope, can prevent further calamities against religious minorities.

When ISIS was attacking the Yazidis in Iraq with genocidal intent, the US intervened and saved tens of thousands of Yazidis who were trapped on Mount Sinjar, under threat of extermination by the extremist Islamist group. Similarly, the destruction of the predominantly Kurdish city of Kobani in Syria was prevented when the US helped local Kurdish forces repel ISIS and take back the town.

Significant funding is needed for religious programming so that citizens of a given country can develop legal practices and cultural tools which offer training and instruction in religious tolerance. In order to address these issues, federal agencies including USAID need to enforce their mandates, as do nonprofits whose mission is to promote religious freedom initiatives.

When these states modify their existing practices, they can be rewarded financially or otherwise depending on the special need of a given country — but tangible results need to be seen before any incentives are granted.

To drive the point home, violators need to fully understand that their transgressions will have consequences. With its tremendous global influence, the United States and the EU can go as far as leveraging international trade or other political deals with a demand of ending violations against religious minorities.

Violators can be punished through sanctions – restricting travel of senior officials, limiting trade, etc.—which could give violating countries incentives to stop discriminatory practices. Approaches to addressing violations against religious freedom, however, cannot be generalized. Each country is different, and the same measures cannot be applied across the board.

We cannot underestimate the importance of education in promoting and fostering religious tolerance and inter-religious dialogue. Modifying textbooks and learning about religions other than one’s own can be an invaluable experience, if it is approached without belittling, disparaging, or dismissing views that are different from the ones we happen to hold.

Positive exposure to other religions can deepen the understanding and appreciation we have of our own faith. As Gandhi aptly observed, “It is the duty of every cultured man or woman to read sympathetically the scriptures of the world. If we are to respect others’ religions as we would have them respect our own, a friendly study of the world’s religions is a sacred duty.”

There are innumerable instances where a country, due to a preexisting alliance or for the sake of self-interest, will not admonish a partner nation for its violations against religious freedom. Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and Iraq are on top of the list in discriminating against Christians, but one does not hear the United States raising this question publicly due to political considerations.

If the United States seeks to make its objections clear to allied nations, it must open a quiet dialogue and pressure them to correct their records on religious freedom.

At the international level, any progress toward ensuring the protection of religious freedom and reducing discrimination against and persecution of religious minorities has been hampered by the failure of the United Nations.

The UN Security Council is overly politicized, and a resolution to stop the persecution of minorities is rarely passed; even then, there is no enforcement mechanism over which all Security Council members agree upon. The UN General Assembly is less effective, as any resolution passed is non-binding and largely ignored by its own members.

The strategies that have been enumerated for addressing religious persecution of minorities in the Middle East do not constitute a silver bullet that will bring a halt to discrimination and abuse. It is a tragedy for the world when any group of persons – whether they be Christians, Muslims, Yazidis, or Druze – are denied their human dignity and the basic human freedom to believe and worship as they please.

The freedom of religion and the dignity of each and every individual will be fully restored when those who now are consumed with hatred for the other, recall and take to heart the words of Matthew 25:40: “Whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.”

*Dr. Alon Ben-Meir is a professor of international relations at the Center for Global Affairs at NYU. He teaches courses on international negotiation and Middle Eastern studies.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect the views of TransConflict.