It’s Time To Re-Examine Australian Defence Policy – OpEd

AUKUS taking focus away from Australia’s immediate security issues

Australians have been told for generations the United States is vital to Australia’s defence and security. The Anglo-centric defence and foreign affairs establishment in Canberra still sees a non-polar world dominated by the US, and is focused on preventing an emerging multi-polar world. This has been national policy since the Cold War, placing an important emphasis on ANZUS. This stance has been supported by think tanks like the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), heavily funded by the pro-US defence establishment, and got Australia involved in a number of meaningless wars and military actions.

The ‘demonization’ of China and Russia is making it almost impossible to put forward alternative viewpoints, where one would be labelled a Sino-Sympathiser or Putin supporter. Iran and North Korea are seen as evil empires, where history plays no credence, as we saw in the Ukraine playbook.

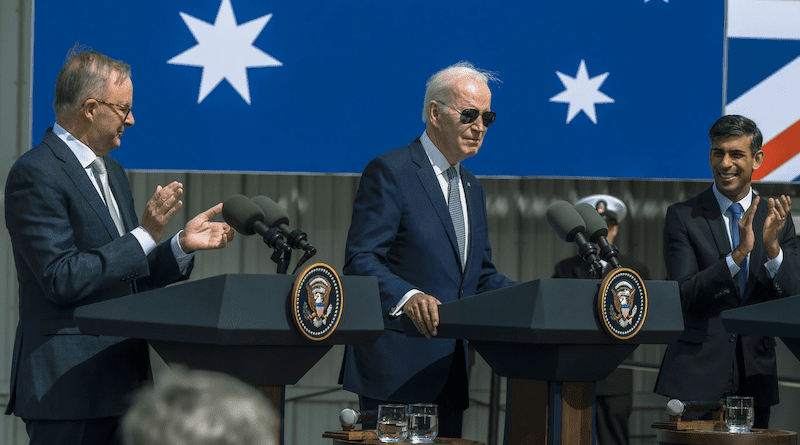

The new AUKUS alliance between Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States locks Australia into US and UK Pacific policy for at least another 30, if not 50 years. As Australia’s defence spending hits AUD 50 billion in the 2023-24 budget, surpassing 2.0 percent of GDP, a proportion of those funds are beginning to be spent on projecting an Australian presence into the East China Sea and Taiwan Straits. These areas are of little true strategic interest to Australia, when there is a wide area of sea to Australia’s west, north, and east, shared with a number of emerging nations.

The 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR), which is a blueprint for Australia’s future defence posture came with a built in assumption that Australia’s security correlates with US policy in the region. The DSR even goes further, saying that the Australia-US alliance will become even more important in the coming decades (see P.18). Building up regional ties was a mere afterthought.

The DSR was a lost opportunity to debate any alternative options concerning Australia’s security future.

Australia’s immediate neighbourhood is a rapidly changing place

Australian defence capabilities have slipped over the last few decades, with critical shortages in manpower. This has happened when our near neighbour’s defence capacity has risen to the point of where some now consider Indonesia to be a middle power, occupying an area to the immediate north-west of the Australian mainland. Australia’s Lowy Institute also cites Indonesia as a regional middle power. Indonesia’s GDP is now 75 percent of Australia’s GDP and could surpass Australia over the next decade.

Indonesia will spend AUD 38 billion on defence this year modernizing its military. Military spending could become even a higher priority for Indonesia if Prabowo Subianto wins the presidential election to be held later this year.

While the political and military dynamics are rapidly changing in Australia’s own neighbourhood, there are distinct risks that Australia’s visons are fixated further afield, completely missing what lays just before us.

Australia’s immediate neighbourhood could have been given more consideration. The attention given to the immediate region appears to be token. The potential security effects of any natural disaster, or any radical shift in any neighbour’s ideology would be of far greater concern than the game of détente being played between China and the US. As we are witnessing in Myanmar, potential regime change is not a far-fetched reality.

What is Australia banking on today with the US?

US defence policy appears flawed and has become overly aggressive over the last 3 years of the Biden administration. Diplomacy as a tool has been downgraded and lack of it, failed to avert massive scaling up of the Russo-Ukraine war over the last two years. A peace agreement was vetoed by the administration more than a year ago, costing endless Ukrainian lives, and stepping up international frictions. There is open speculation over the real drivers of this war from the US standpoint. This leaves question marks as to who is really driving US defence actions. Is it the Secretary of State Antony Blinken, the Defence Department/Pentagon, former Obama administration people, or Preseident Biden himself? This doesn’t relate exclusively to the Biden Administration, US foreign/defence policy has been heading in this direction across previous administrations.

We hear about China’s expansionary presence in the South China Sea, a place it has been in for more than a thousand years. A large percentage of citizens of countries around the South China sea were Chinese migrants. With the exception of China’s advance across the border of Vietnam in 1979, China has not invaded any country. China’s activities in its immediate region are interpreted very differently to the way Australia’s strategic and defence experts are interpreting the presence (expansion), reasserting influence after a 65-year hiatus. This issue requires much more examination than was provided in the DSR.

In contrast, China’s Pacific theatre and shipping routes are surrounded by US bases in Korea, Japan, Guam, along with a heavy naval presence ensuring ‘freedom of navigation’. The US has a containment doctrine in place, which Australia subscribes to through the AUKUS nuclear powered submarine plans. Indonesia has deep reservations about AUKUS.

US defence competency must be questioned with the haphazard withdrawal from Afghanistan and reinhabiting of the country by elements of Al Qaida. The unchecked run of the Taliban is strengthening the Pakistan Taliban which could topple the government in Islamabad, allowing the Taliban to control Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. Iran has gained access to billions of US Dollars, which is funding Hamas and the Houthis in Yemen. Although not widely reported in the legacy media, merchant ships are being sunk by low cost Houthi missiles on a regular basis in the Gulf of Aden. The failure of US high technology weapons to keep shipping safe will require a drastic rewrite of military tactics. The US is depleting its own stockpile of weapons in Ukraine, and terrorist cells are establishing themselves in the continental the United States.

Much of the above could have been preventable. The soundness of current US policy should at least be discussed to ensure Australia is not harmed as a party to some future conflict unnecessarily.

Australia’s unique issues in the region

Being antagonistic towards Australia’s largest two-way trading partner China defies logic. We can observe and learn from the results of the Morrison government’s approach to China. China trade is just too important to put at risk. In 2022-23, the two-way trade with China increased 12 percent, totalling AUD 316.9 billion. This made-up 26 percent of Australia’s two-way trade with the world.

Canberra’s Anglo-orientated bureaucrats really need to learn from neighbours in the region how diplomacy could better be conducted in the region. We are no longer the ‘superior’ white man of the south.

Australia’s greatest strategic threat will not be from military attack. It will most likely come from a massive natural disaster to the north. This could lead to massive casualties and exodus to the shoreline of Australia. This would happen with little warning.

China has already become extensively involved in the Australian economy. Now, 5.5 percent of the population in Australia are Chinese. This is an important cultural connection to China, as China sees the diaspora as overseas Chinese citizens. One of the best ‘bellwethers’ to measure the Australian-China relationship is the number of tourists that visit each year. When this picks up, then we will know the Australian-China relationship is becoming healthy once again.

These are the cultural issues that will help to prevent any mishap with China.

Meanwhile, Australia must look at how best to defend itself in the immediate region. Submarines for coastal surveillance would be good. Nuclear powered submarines bought on the ‘never-never’ might not even be around when they might be needed.

Australia’s biggest defence is diplomacy and soft power. Australia must move beyond just transactional relationships with its neighbours. Much closer relationships must be built with our neighbours, and this means integrating the military, if possible. Our best defence and also biggest threat is Indonesia.

Australia shouldn’t be playing other nation’s games. It has its own game much closer to home.