A Belligerence Towards Beijing That Is Unsettling – OpEd

By Observer Research Foundation

By Manoj Joshi*

The intensifying head-to-head clash between the United States and China has set alarm bells ringing. Beginning with a trade war in 2018, U.S. policy towards China has morphed into a draconian technology denial regime aimed at hobbling China’s rise. Simultaneously with a view of preventing any Chinese military venture to capture Taiwan, the U.S. has taken major steps across the Indo-Pacific to shore up its military edge.

The belligerence towards Beijing is a bit unsettling. This was a quasi-ally whose friendship cemented the rise of China, but, today, Washington wants to stop it on its tracks. For several years, its own allies such as Japan and the European Union (EU) resisted U.S. pressure to follow its new course, but the war in Ukraine and the very obvious Chinese support for Russia seem to have settled the debate.

A détente is distant

The recent G-7 summit put forward a united West plus Japan view on China. Besides condemning its “economic coercion” and “militarisation activities”, it created a new group to deal with hostile economic actions, mainly by China, to coerce nations. On the table was a more draconian measure to review all outbound investment to China on the issue of security.

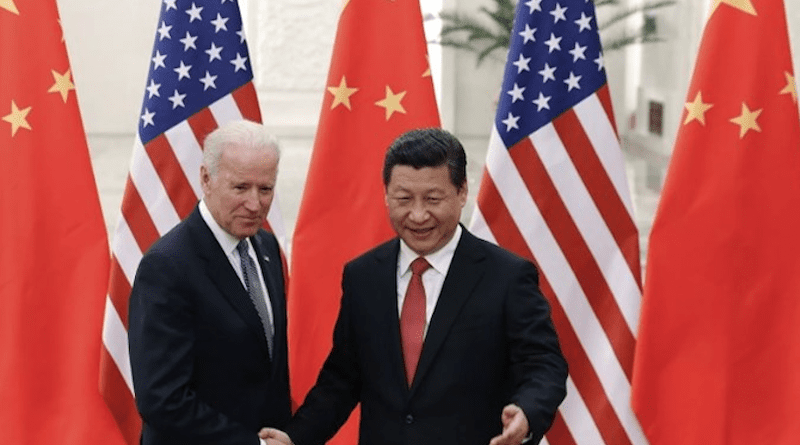

At the end of the G-7 meeting, U.S. President Joe Biden announced that he expected to soon “see a thaw” but the relationship is hardly heading for any kind of a détente. Both countries are jostling for power and influence across the world. “Extreme competition” over technologies may have initiated the conflict, but their insecurities are increasingly bringing their military and nuclear instruments to the fore.

Mr. Biden is outlining what is called the new Washington Consensus designed to re-establish U.S. hegemony. The old one, which was based on free markets, embraced China with the hope it would, over time, integrate into the American-led liberal international order. But China, in a sense, went rogue.

“Extreme competition” over technologies may have initiated the conflict, but their insecurities are increasingly bringing their military and nuclear instruments to the fore.

Technology denial to China is one aspect of the strategy. The other is to turn the old Consensus on its head by protectionism and a new industrial policy based on state subsidies. A third element is to reach out to China and claim that all that Washington wants is to “de-risk and diversify” its economy, and guard its key technologies using a “ small yard,[with a] high fence”.

Just what the U.S. goal is, is not clear. Most experts say that while controls may slow China, it is impossible to prevent it from developing its own technologies. The Russian experience shows too that sanctions are not easy to work either.

Seeing U.S. export restrictions to over 600 Chinese entities, all in the last couple of years, Beijing does not see much difference between “de-risking” and “containment”. Its immediate response to the G-7 was to order its infrastructure companies to stop buying from Micron and dressing down the Japanese Ambassador in Beijing over the G-7 communiqué.

French President Emmanuel Macron’s comment on refusing to be a vassal state of the U.S. represents a tip of the iceberg of the worries of Europe and allies such as South Korea. Now, there are signs that resistance is also building up in the U.S. to the strategy of the Biden administration. The chief of Nvidia, world leader in AI computing, has warned that the battle over chips risks “enormous damage” to the U.S. technology industry. He said that China made up roughly one-third of the U.S. industry’s market and would be “impossible to replace as both a source of components and an end market for its products”. There are more than a dozen companies such as Micron who derive between 25% to 50% of their revenue from China. Almost all the big names in the U.S. have a strong presence there anyway.

A dangerous game of ‘chicken’

The U.S. wants China in the new Washington Consensus on its terms, the hardest of which are setting limits as to what China can aspire to in the fields of technology and military. This is something Beijing naturally resents. The two now seem to be involved in what the Americans call a game of “chicken” which comes with a high risk of miscalculation, war or a messy global economic breakdown.

The problem is that where the old Washington Consensus was largely in the area of economics, the new suffers from an overdose of geopolitics which is also feeding into local U.S. politics as well. It is based on the erroneous belief that the U.S. is in a state of decline and that the old Washington Consensus gutted U.S. industry and impoverished its middle and poorer classes.

That it vastly enriched its well off is another matter. Instead of dealing with this outcome through effective policy, the Democrats and Republicans fiddled around with their pet policies — one encouraging entitlements and the other tax cuts.

The U.S. wants China in the new Washington Consensus on its terms, the hardest of which are setting limits as to what China can aspire to in the fields of technology and military.

This has created a toxic political atmosphere that both parties, increasingly dominated by their more extreme wings, are seeking to exploit. The one area they seem to agree on is that China is responsible for their alleged ills.

Mr. Biden seeks to introduce nuance into his approach to China. But Republican Hawks in Congress have created a Select Committee on China chaired by China hawk Mike Gallagher who said in its first meeting in March that the competition between China and the U.S. was “an existential struggle over what life will look like in the 21st century”.

In a recent interview, Henry Kissinger warned against misinterpreting Chinese behaviour. China wanted to be powerful, but not necessarily a global hegemon in the American style. The chances of that happening are not high anyway. The U.S. itself is by far the most powerful country in the world, militarily and economically, and current trends suggest that it is likely to remain so. With its allies the EU, the United Kingdom, Japan and Australia, it will continue to be ahead of China in every measure.

The issue is China’s diplomacy

China has achieved a great deal. It may have stolen IP, and will continue to do so, but it has also put down serious money in developing its tech and education sector.

Where it seems to have lost out is in its diplomacy where it has created significant adversaries through its assertive behaviour, be it in the East Sea, South China Sea or the mountains of Ladakh.

In their own way, both are privileging security over other issues when it comes to their global outlook. And therein lies the danger to the rest of the world. In this, the U.S., by far more powerful than China, must take the larger share of the blame.

As it is, the U.S. is not the smartest country when it comes to dealing with global geopolitical challenges. Its enormous wealth and power and echo-chamber think tanks make it difficult for it to understand distant countries and cultures. But worse is the American tendency to fight first and ask questions later. Vietnam, and the recent examples of Afghanistan and Iraq are proof of that. Worries are that something of the sort may happen in the case of China as well.

U.S. estrangement with China enhances India’s geopolitical value, something the present ruling dispensation is revelling in. But while the Sino-American hostility may bring benefits to India, a breakdown would be catastrophic, for not just India but also the world. New Delhi is not unaware of this and has stepped carefully in its own relationship with China, whether at the global and regional levels or the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh.

About the author: Manoj Joshi is a Distinguished Fellow at the ORF. He has been a journalist specialising on national and international politics and is a commentator and columnist on these issues. As a reporter, he has written extensively on issues relating to Siachen, Pakistan, China, Sri Lanka and terrorism in Kashmir and Punjab.

Source: This commentary was published by Observer Research Foundation and first appeared in The Hindu.