Increasing Numbers Of Unaccompanied Children At The Southwest Border – Analysis

By CRS

By William A. Kandel

Since early 2021, annual encounters involving unaccompanied alien children (UC, unaccompanied children) at the U.S.-Mexico border by the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) have remained at record-high levels (Figure 1).

Encounters include both Title 8 (immigration law) apprehensions and Title 42 (public health law) expulsions. In the first eight months of FY2023, UC encounters by CBP’s U.S. Border Patrol (88,089) between U.S. ports of entry (POEs) were roughly comparable to the first eight months of FY2022 (98,629), the year when UC encounters reached an all-time high (149,093). In FY2021, total UC encounters numbered 144,834, a record then and almost double the previous record set in FY2019 (76,020).

Since February 2021, UC encounters have consistently exceeded 8,500 per month, higher than any period since CBP began publishing UC statistics. The highest monthly total ever recorded (18,715) was in March 2021.

Notes: *FY2023 figures represent the first eight months of FY2023. FY2020 and FY2021 figures include Title 8 apprehensions and Title 42 expulsions; all other years’ figures include only apprehensions. Figure excludes UC deemed inadmissible at U.S. POEs. Figures 1 and 2 begin with FY2009, the first year when the TVPRA was fully enacted.

FY2020 UC encounters (30,557) were the lowest since FY2012 (24,481). They declined largely because of generally reduced migration from the COVID-19 pandemic and related public-health border enforcement. In March 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention exercised authority under Title 42 to prevent the spread of COVID-19 by allowing CBP to rapidly expel individuals who lacked valid visas or were apprehended between POEs. In November 2020, a federal judge halted UC expulsionsunder the Trump Administration, and in February 2021, the Biden Administration formally ended UC expulsions. The Title 42 authority to rapidly expel those who lacked valid visas or were apprehended between POEs ended on May 11, 2023. CBP currently apprehends all UC under Title 8 authorities.

Unaccompanied alien children are statutorily defined as minors under 18 who possess neither lawful U.S. immigration status nor a parent or legal guardian in the United States immediately available to provide care and physical custody. UC treatment and processing are governed by several statutes and a legal settlement. These include the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA), which requires children from noncontiguous countries (e.g., the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras) to be transferred (referred) to the care and custody of HHS’s Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). They are also put into formal removal proceedings, where they may apply for asylum or other forms of immigration relief. In contrast, UC from Mexico and Canada who are not trafficking victims or do not fear persecution in their countries of origin may be promptly repatriated.

Over the past decade, the origin-country composition of UC has shifted substantially. In FY2009, Mexican children accounted for 83% of UC apprehensions. In the first eight months of FY2023, they accounted for 20%. Children from noncontiguous countries outside of the Northern Triangle increased from 1% of all UC apprehensions in FY2009 to 11% in FY2023. In FY2023, 75% of UC were ages 15-17 and 63% were male, proportions that have remained relatively stable since FY2012.

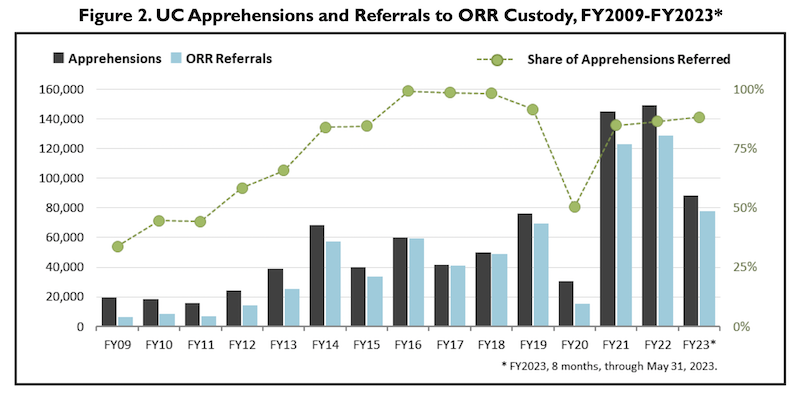

ORR’s caseload of UC reflects both the increase in total apprehensions and the change in origin-country composition (Figure 2). As Central American children increasingly dominated total UC apprehensions, the percentage of all apprehended UC referred to ORR also increased. In FY2009, when children from noncontiguous countries comprised 18% of all UC apprehensions, referrals made up 34% of all apprehensions. By FY2023, when noncontiguous country children comprised 80% of all UC apprehensions, that percentage increased to 88%.

Notes: *FY2023 data represent the first eight months of FY2023. UC apprehended in one fiscal year may be referred to ORR in the next year, but because CBP must refer UC within 72 hours, the percentage of such children is relatively small.

Several federal agencies handle UC apprehension, processing, and U.S. placement or repatriation. CBP apprehends, processes, and initially detains UC and then refers them, if appropriate, to ORR. DHS’s U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) transports children from CBP to ORR custody. ORR shelters and seeks placement of UC with sponsors, usually family members, as they await their immigration hearings. Most UC apply for asylum, and DHS’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Servicesadjudicates initial asylum petitions. The Department of Justice’s Executive Office of Immigration Review conducts immigration court proceedings. ICE repatriates UC who are ordered removed. Most UC wait years for their hearing and are required to attend school in the interim. Children who reach 18 age out of UC classification and are treated as unauthorized adults.

To move UC promptly out of CBP facilities when apprehension levels have surged, ORR has used large temporary influx facilities to supplement its conventional shelters. Such facilities scale up relatively quickly, are often sited on federal property, and are not state licensed. Child advocates contend that stays in these facilities can cause lasting emotional trauma for children. Currently, ORR shelters less than 5% of UC in these facilities.

In February, reports surfaced that UC in the United States were working illegally in jobs that often violated U.S. child labor laws and conflicted with their sponsors’ obligations to ensure children attended school. Some suggest that UC migration to the United States reflects individual and household responses to incentives created by the differential treatment of noncontiguous country children by the TVPRA. Other explanations for UC migration continue to emphasize the flight from poverty and violence.

About the author: William A. Kandel, Specialist in Immigration Policy

Source: This article was published by the Congressional Research Service (CRS)