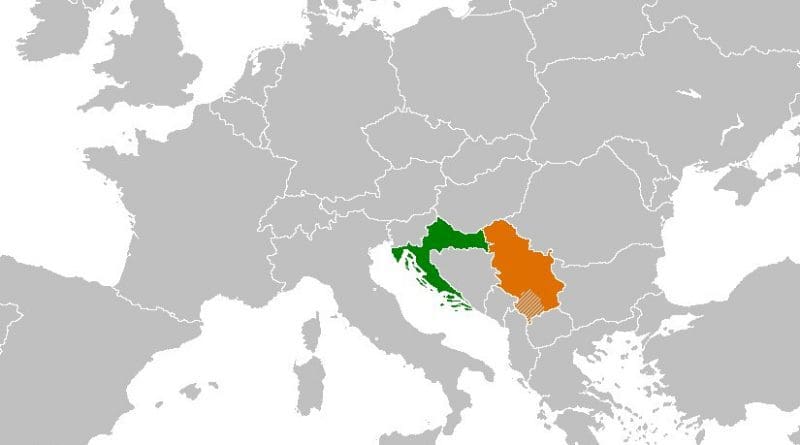

Croatia-Serbia Tensions Escalate Into Diplomatic War – Analysis

By Sven Milekic and Milivoje Pantovic*

Relations between Croatia and Serbia have plunged in recent days amid exchanges of inflammatory protest notes and harsh statements from politicians on both sides.

The latest crisis has been prompted by day-to-day internal political issues in both countries – and by the fact that both countries are led by conservative, if not nationalist, politicians, experts said.

Tension is also expected to escalate even more in coming weeks as Croatia gears up for the annual anniversary celebration of its victorious 1995 military operation, Oluja, (Storm), on August 5, marking the day when the Croatian military quashed a Serb revolt in south-west Krajina region.

This operation, celebrated in Croatia as much as it is mourned in Serbia, has been a cause of major ethnic tensions and disputes between the two countries for years.

“We have a process of returning to nationalism on both sides. Both sides are ‘grooming’ their anti anti-fascist traditions,” Zoran Gavrilovic, director of the Bureau for Social Research in Belgrade, told BIRN on Friday.

Relations between Croatia and Serbia have plunged in recent days amid exchanges of inflammatory protest notes and harsh statements from politicians on both sides.

The latest crisis has been prompted by day-to-day internal political issues in both countries – and by the fact that both countries are led by conservative, if not nationalist, politicians, experts said.

Tension is also expected to escalate even more in coming weeks as Croatia gears up for the annual anniversary celebration of its victorious 1995 military operation, Oluja, (Storm), on August 5, marking the day when the Croatian military quashed a Serb revolt in south-west Krajina region.

The latest diplomatic salvoes were preceded by months of pressure from EU-member Croatia on EU would-be member Serbia, designed to force Belgrade to change or abolish its law that gives Serbian courts jurisdiction to prosecute crimes committed anywhere in the region during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s. For years, this law has been another point of dispute in the region.

Tensions escalate quickly after truce:

Croatian President Kolinda Grabar Kitarovic and Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic initially tried to improve matters by signing an agreement on improving bilateral ties between the two countries at the end of June.

The agreement was designed to enhance protection of each other’s minorities, define the state borders between the two countries and help solve ongoing problems that burden their tricky relationship.

But relations suffered a new blow on July 18 after the EU officially opened negotiations with Serbia on Chapters 23 and 24 of its accession talks, after which Croatian officials demanded again that the controversial war-crimes law be struck down.

“Serbia has an obligation to change the law on war crimes… this stems from the criteria of the EU and, if Serbia wants to join the EU, it will have to be abolished,” the Foreign Minister in Croatia’s current “technical” government, Miro Kovac, said on July 21.

Kovac claimed the Serbian authorities were well aware that they had to change the law but were “acting in front of their public and saying they don’t want to do it”.

Kovac warned that if Serbia issued new indictments about alleged war crimes committed by veterans of the Croatian independence war, “harsh measures from Croatia will subsequently follow”.

Already tense relations were worsened on July 27, after a group of Croatian right-wing nationalists disrupted a rally marking the anniversary of an anti-Fascist [mainly ethnic Serbian] uprising in 1941 in the village of Srb against the Independent State of Croatia, NDH [the Nazi puppet state which governed Croatia and much of Bosnia during World War II]. This was strongly criticized by Serbia.

The situation also worsened after Croatian courts on July 26 annulled the verdict issued by the Yugoslav communist courts in 1946, convicting Croatian Catholic leader Archbishop Alojzije Stepinac of Zagreb of collaboration. [Stepinac had praised the establishment of the NDH in 1941.]

On July 28, the Croatian courts also ordered a retrial for Branimir Glavas, a former Croatian army general found guilty in 2009 of torturing and murdering Serb civilians in the city of Osijek in 1991. He had been sentenced to ten years in prison.

Exchange of bitter diplomatic notes:

The two countries exchanged several diplomatic protest notes on July 26, 28 and 29.

After receiving a protest note from Serbia regarding the case of Archbishop Stepinac, Croatia’s Foreign Minister on Wednesday accused Serbia of trying to destabilize it.

“It’s a petty attempt to destabilize Croatia in a sensitive period after the dissolution of the parliament and before the celebration of ‘Storm’. This is a recipe from the 1990s, reminiscent of [Serbian wartime President Slobodan] Milosevic and the Greater Serbian aggression,” Kovac said.

Kovac told Serbia to stop interfering in Croatia’s internal affairs, calling the protest note about Stepinac “a made-up story” and adding that the controversial Archbishop was “a clear victim of the Communist regime”.

However, Serbia declined to back off. Reacting angrily to the abolition of the Glavas verdict, Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vucic on July 28 said the position of Serbs in Croatia, as well as that of all Serbs west of the river Drina [i.e. in Bosnia as well as Croatia], was getting worse by the day.

“Our job is to make decisions responsibly and rationally, not to show that type of hatred that we feel elsewhere. We need to act responsibly, seriously and calmly,” Vucic said, adding that he could not understand the reason for the verdicts on Glavas and Stepinac.

Meanwhile the Serbian ambassador in Croatia, Mira Nikolic, refused to accept one of the Croatian diplomatic notes on Thursday, complaining of its “inappropriate” content.

Serbian Foreign Minister Ivica Dacic said the ambassador had refused to accept the note because it insulted the whole Serbia.

“We will continue with our policy of good neighborly relations but we will protect our interests,” Dacic told an impromptu press conference on Thursday.

“We believe that this is a clear continuation of Croatian policy which goes towards the rehabilitation of not only the NDH, but also criminals from the last war [in the 1990s].

“On this occasion, as well as at the incidents in Srb and many other incidents that have escalated in Croatia in recent times, we have delivered a protest note to Croatia,” Dacic recalled.

In its newest protest note on Friday, the Croatian Foreign Minister called on Serbian officials “not to use the vocabulary of the failed Yugoslav communist system and aggressive Greater Serbian policy from the 1990s that was military and morally defeated.”

Croatian political analyst Zarko Puhovski told BIRN on Friday that the exchange of angry messages from both sides reflected the fact that neither side “understands reality.

“The reality is that [as an EU member] Croatia is institutionally superior as it never was before,” he said.

“Croatia doesn’t understand that and doesn’t know how to behave and not to react to provocations, while Serbia simply can’t stand that Croatia is superior and simply provokes it.”

Puhovski concluded that the quarrel had nothing to do with the campaign for the September parliamentary elections in Croatia, explaining it more as “a long present phenomenon that will continue to exist” long after the elections are over.

Gavrilovic in Belgrade saw things differently. “Both states have failed to cleanse their societies of fascism. There is fascist-ization of society both in Serbia and Croatia,” he said.

“However, I do not think that it is as brutal in Serbia as it is in Croatia,” he concluded.