Sufism: Lost Chance Of Islamic Reformation – Analysis

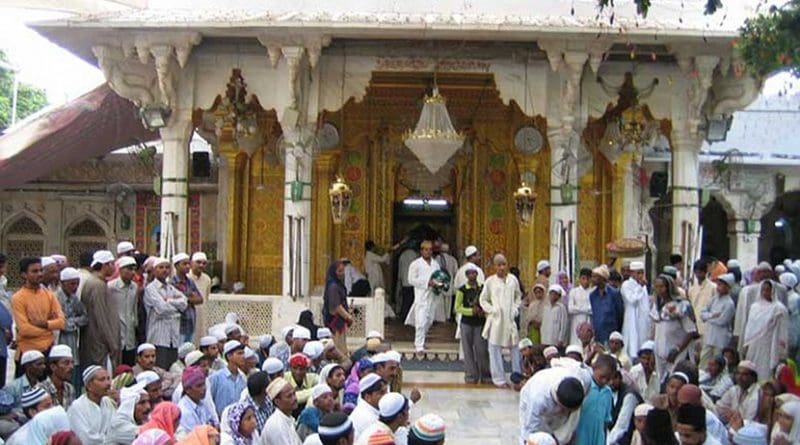

A month ago many Christians marked the 500th anniversary of Reformation, which brought profound change to the development of the Western world. A few days ago Daesh members attacked a Sufi mosque in Egypt killing about 300 its members – one of the deadliest terrorist acts in the country. This article attempts to connect and reflect around a few dots among Islam, Reformation and modern politics.

Six hundred years ago, sometime around 1417, the Azerbaijani poet Imaddadin Nasimi was executed in Aleppo for blasphemy by being skinned alive. He followed his teacher, Fazlullah Naimi, who had been executed several years earlier for apostasy. Nasimi and Naimi belonged to Hurufi, a branch of Sufism, which preached that every man contains a piece of God and through self-perfection every individual could reach God’s mind.

“Both worlds can fit within me, but in this world I cannot fit. I am the placeless essence, but into existence I cannot fit.” Nasimi’s most famous verses endure in Sufi teachings, though his particular mystical form of Islamic belief and practice, seeking the unification of divine, love and knowledge, is fading away today.

Six centuries after Nasimi’s execution, the city of Aleppo has become a symbol of hate, destruction, geopolitical games and war. Syria is torn between secularism and religious fundamentalism, dictatorship and anarchy, Sunni and Shia, the United States and Russia. Yet, though many different struggles intersect in the Middle East, Islam remains central in any discussion either about the fate of the region or even far beyond its boundaries.

Numerous experts and scholars are trying to answer the question of why religious radicals claiming Islamic tenets became so popular, and whether Islam and the rise of terrorism are somehow connected. How can one reconcile the fact that while once Islam and the Arab caliphates sparked the development of arts and science during the Middle Ages, but in the present day most Muslims majority countries lag significantly behind the developed world and lack any meaningful contribution to the innovation of new technologies.

What is clear is that many Muslim majority states which tried to promote secularism, while ignoring or suppressing their Islamic foundations, have failed. Those states needed not only institutional secularism but also support from supportive Muslim clerics, those embracing an Islamic theology and practice which would accept modernity and promote technological advancement. One such option could have been Sufism, but today Sufism is a fading practice and under increasing attacks from fundamentalists who gain greater and greater strength and popularity in Islamic world.

Understanding the dynamic of modern political thoughts among Muslims requires a brief excursion into the development of political Islam for the last two hundred years.

When comparing Islam and the Middle East with Europe and Christianity, populists in the West claims that the tenets of Christianity were conducive to scientific and social progress. In their argument, Christendom is inherently advantaged and much superior to the Muslim world. Yet this position ignores or glosses over the centuries when the spread of Islam in Asia and North Africa coincided with more advances when compared to medieval Europe. Despite their assertions, a thoughtful reflection over the entire – not just recent – history of Christianity in Europe suggests that this religion for many centuries actually impeded scientific progress. It was only after the Enlightenment, when Europe was freed from the yoke of religious zealots, that secularism became an important instrument for industrial revolution and technological progress. The ostensible lesson to those who ponder over the fate of Muslim countries today is that secularism is essential for modern advanced societies.

From classical scholars such as Ernest Renan and Max Weber to modern ones like Bernard Lewis, and experts, for example, Shadi Hamid and Anshuman Mondal there is a strong opinion that Islam is not compatible with modernity, liberalism and secularism. Other scholars, however, such as Johann Arnason and Armando Salvatore think differently.

Some historians point to Protestantism as the specific branch of Christianity which promoted the spirit of capitalism and subsequently led to the creation of modern society. Nick Danforth argues that thanks to subjugation of religious authority to the power of a sovereign in Europe, for example in Britain under Henry VIII, true reformation occurred in Christianity. He opines though that we should not expect Islamic “Luther” because the two religions follow quite different historical paths.

The idea that Islam lacked a ‘reformation’ type offshoot and therefore, Muslim countries did not succeed in the promotion of scientific progress and adaptation of modernity is quite strong among Western experts. However, I argue that as a matter of fact, Islam had and still has such a modernist path: Sufism. In the meantime, we should be careful when we compare one religion to the other. There are quite different theologies behind each and any comparison should be made cautiously. Further, one might ask a principled question, whether any religion requires ‘reformation’ at all in order to accept a modern lifestyle.

For example, Buddhism in its original form showed a great extent of flexibility for modernity. Probably, this happened because Buddhism was a religion concentrated less on mundane matters rather than spiritual ones. Hinduism, on the other hand, remains quite hostile to social changes and upholds the caste system in India. While India as a state develops technologically thanks to a strong secular constitution, many ethnic and religious communities within Indian state are very patriarchal, maintaining inequality among their members.

Looking at the last two hundred years of political Islam and its attempts at reformation, one might conclude that a modernist strive has failed. There has been little success within the Arab world, and it is seemingly problematic where it appeared most successful, in Turkey. Various factors such as Western colonialism, authoritarianism and corruption have been blamed; eventually, in every case, the cause of secularism in Islamic countries has significantly eroded.

Initially, however, Muslim reformers were enthusiastic about embracing modernity, and secularism had a certain place in this reformation exercise in the second half the 19th century. Islamic philosophers mainly focused on two pairs of issues: how to embrace technological revolution and respond to western domination, and how to return to “true Islam” and reconcile it with modernity. Subsequently, over the course of the next two centuries the idea of modernity was jettisoned and most clerics became obsessed with recapturing the so-called “authentic” Islam of the Prophet Muhammad.

One of the foremost founders of modern political Islam was Sayyid Jamal al-Din Muhammad bin Safdar al-Afghani (1838-1897) from Afghanistan, who advocated rationalizing Islam so as to absorb Western scientific innovations and, in turn, resist European colonialism. He supported ijtihad – independent interpretation of the sources of the Islamic law, the Qur’an and the Sunnah, and was against the absolute power of monarchy. He was forced to leave Turkey for Egypt to escape prosecution by the Sultan and royal clerics. That fate of prosecution and exile was the destiny of almost all subsequent Islamic thinkers, Muhammad Abduh, Sayyid Qutb and others. Their doctrines were perceived as not only combating Western influence, but as also directed against the rulers within Muslim states.

Another great Islamic thinker Namik Kemal (1840-1888), Turkish by origin, called for the solidarity of all Muslims and for modernization in order to resist the plan of colonial powers to dismember the Ottoman Empire. He called also for constitutional amendments to make the Ottoman Muslim state more representative and inclusive. Namik Kemal strongly emphasized the idea of a single Islamic ummah on the eve of the collapse of Ottoman Empire. However, failed reformists attempts in the Ottoman state on one side and the rise of Arab nationalism on the other side, partially inspired by Great Britain, diluted the Pan-Islamism movement.

Al-Afghani’s prominent disciple Muhammad Abduh from Egypt (1849-1905) pressed for further reforms of Islam. In his opinion, Islam was inherently adaptable and should be modernized. Abduh’s other students, Rashid Rida and Ali abd al-Raziq, would advocate further reformations to strengthen the Muslim faith. They preached for the creation of an Islamic state, but at the same time Rashid Rida supported Darwinism and the free interpretation of Islamic primary sources, while al-Raziq supported separation of state and religion.

As a whole, Islamic thinkers of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century promoted enlightened versions of reforms. However, that was before Western powers such as Britain and France colonized the region. Before Western colonization in the Middle East, Islamic reformations had some ideological ties to Europe as a source of modernization. Some Arab philosophers like Rifa al-Tahtawi propagated the principles of the French Revolution. Once colonization began, Islamic reformation efforts became increasingly militant and anti-modernist, splitting into two major movements: Islamic socialism and fundamentalism.

Muhammad Abduh’s theories would be modified by Hassan al Banna (1906-1949), the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood. Al Banna reversed reformation from modernization towards the creation of an Islamic state based on sharia. Yet he remained a strong critic of tyranny and supported the idea of social justice. The minds of politically active Muslims were attracted to such philosophers as Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966), active member of Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, executed by Egyptian president Abdel Nasser, and Taqi-ud-deen an-Nabhani (1909-1977) from Jordan, founder of Hizb-ut-Tahrir. Both organizations are still very active and were early templates for Al-Qaeda and its founder Osama Bin Laden. They and other like-minded fundamentalists asserted that everything which comes from the West had one purpose: to subjugate and enslave Muslims; therefore, everything Western should be categorically rejected. The true system of statehood for Muslims is an Islamic state where they can freely develop themselves and strengthen their faith.

Parallel to the anti-Western movement, Islamic socialism spread throughout the Middle East in the mid-20th century, founded by several thinkers: Ubaidullah Sindhi, Ghulam Ahmed Parvez, Salah ad-Din al-Bitar and others. This branch of political Islam gave rise to Abdel Nasser in Egypt, who first and firmly stood against colonial powers during the Franco-British-Israeli invasion in Suez channel in 1956. Islamic Socialism spread to Syria, Iraq, Algeria, Libya, Yemen and Pakistan in various versions led by powerful figures such as Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in Pakistan, Ahmed Hassan Al-Bakr in Iraq, Hafez Assad in Syria and Muammar Qaddafi in Libya (whose association with socialism was marred by bizarre habits and dictatorship).

However, inefficient economic reforms, increasing authoritarianism and the defeat of Arab countries by Israel in 1967 were a fatally wounded Muslim socialism. After the invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviets, the one European power that was supposedly anti-colonial, the only movement most Muslims thought could be a valid response to Western hegemony was what we call today ‘fundamentalism’. Islamic thinkers of the second half of the 20th century preached for “purity” of Islam, particularly against western philosophies such as liberalism and democracy, which was viewed as an alien form of governance imposed by Western colonialists.

Two forces were responsible for the erosion of an Islamic modernist reformation. First and foremost it was Western colonialism; over the course of the 20th century, western states and societies became associated with domination and occupation. The geopolitical struggle between the United States and the USSR added greatly to the erosion of secularism, which – bizarrely – was often viewed in Western capitals as an offshoot of Communist Moscow’s influence. Finally, in Afghanistan, the US promoted Islamic rebels, and concurrently their anti-reformation message, to oust the Soviet army.

As Khaleb Khazari-El noted “fundamentalism prevailed over the threats of nationalism and communism in the long 20th-century contest as to which ideology would bear the anti-imperialist mantle in the Islamic world.”

Against this geopolitical background, Sunny and Shia radicals gained momentum in the Middle East. The Iranian revolution of 1978-1979 brought a new dimension to political Islamism, making the dreams of conservative traditional visionaries possible. Despite the fact that several Islamic countries, such as Saudi Arabia, already possessed theocratic governance systems based on sharia, more than any other the Iranian revolution was directed against the West, monarchy and secularism at the same time.

Even though Iran is a Shia majority country, one of only a few at that time, the spread of political Islamism became stronger throughout the entire Muslim world after 1978.

Modern Islamism is fundamentally a response to the policy of Western countries and should be understood within the context of colonialism. This is not to simplify or put blame only on Western powers for the fate of many Muslim majority countries today.

Yet jihadism and all the many varieties of militancy in the Middle East were a reaction to external factors. After the end of the Cold War, the rise of right-wing Israelis and evangelicals in the West, especially during George W. Bush administration, further played a role in strengthening a reactive religious zeal among Muslim radicals.

As many Muslim majority countries and territories – Palestine, Kashmir, Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan, Rahinye State of Myanmar, and some others are subjected to occupation or ethnic cleansing, Muslim points to the inaction of Western countries and an apparent “double standard” compared to their support that Christians in South Sudan and in other places received from the West. Such regional conflicts remain the main feeder of interreligious and inter-civilization tensions, and will continue to be used by radicals.

Today, Political Islamism is fact of life, and takes larger space within all Muslim countries, while secularism is under the siege. As Uğur Kömeçoğlu notes, Islamism seeks to energize and organize Muslims to struggle against what it perceives as a Western-dominated world system and juxtapose Islam “against secular, pluralistic and liberal understandings of the “emancipated self” and the democratic public sphere.”

The sectarian fight between Sunni and Shia radicalizes both groups and leave little space for other Islamic practices such as Sufism. The latter should not be termed as a branch of Islam, rather indeed ‘practice’. Both major Muslim groups, Sunni and Shia, have Sufi followers. Historically many notable Sufi philosophers have come from both Sunnis and Shias, with multiple doctrines and contexts to be invoked and practiced. For this very reason, Sufism had a potential to be a major reformist path, uniting adversary camps within Islamic faith.

Sufism, unlike Protestantism in Christianity, existed almost from the beginnings of Islam. As Almando Salvatore pointed out, “the enduring strength of Sufism is due to the fact that its remote roots are as old as the translation of Muhammad’s message into pious practice by his companions, yet it is also particularly capable of adapting to changed socio-political circumstances”. Sufism historically was transformative thinking, with a primary emphasis on spiritual meditation and education. Commonly associated with eastern vagabonds, such as dervishes with their whirling rituals, Sufism, also produced prominent philosophers, astronomers, mathematicians and poets such as Ibn Rushd (known to the West as Averroes), Ibn Sina (Avicenna), Jalaluddin Rumi, and many others. Sufis were associated with spread of Islamic culture beyond the Middle East and in the aftermath of the fall of the Arab caliphate, to India and East Asia on one end, and to Africa on another. Perceived as individualists preaching asceticism, Sufis sometimes took active part in political or social life of Muslim communities, forming orders – tariqats under the rule of leaders, sheikhs or mawlas.

During the colonial era, Sufis quite often were at the forefront of struggle against imperial domination in Africa and the North Caucasus. While some Sufis adhered to the strict practice of major Islamic traditions, others deviated quite significantly from conservative interpretations of the religion. Certain Sufi philosophers had theological links with other religions and teachings, such as the kabbalah. As Vincent Cornell stresses in Realm of the Saint: Power and Authority in Moroccan Sufism, Sufism combines sometimes opposite teachings: peace and militancy, self-reflection and political power, Islamic purity and esoteric traditions. What serves as the common denominator for all Sufis is the goal of achieving divine truth through mystic connection with God. Most Christians who have converted to Islam in the last hundred years in the West were actually attracted by Sufi mysticism.

Rafiq Zakaria in The Struggle Within Islam: The Conflict Between Religion and Politics, suggests that, paradoxically, while many Sufies “refused to bow down to authority, their teachings made the task of governments, especially in states with mixed ethnic and religious populations, much easier. Had it not been for the environment of peace, goodwill and mutual understanding that they generated, Islam would not have become so readily acceptable to non-Muslims nor would Muslim rulers have been able to run their administrations as peacefully as they did.”

This feature among Sufi Muslims has led some policy makers, both within Muslim countries and in the West, believe that Sufism can promote so called moderate Islam. In some countries, like Morocco and Algeria, Sufism is backed by incumbent governments. In 2007, a US government funded RAND Centre for Middle East Public Policy report recommended supporting Sufism and fostering networks of moderates within Islam.

However, expert Fait Muedini believes that “promoting Sufism, particularly at the expense of other Islamic traditions, is highly problematic”. In his opinion, “the perception of Sufism as a Western, moderate, or tolerant form of Islam cements a dichotomy between “good” and “bad” understandings of the religion”. Such division can deepen a gap between different branches of Islam and put those Muslims, who sometimes for legitimate reasons dislike their governments, into a disenfranchised group. On the other hand, peaceful and so-called Westernized Muslims, who actually do not practice Islam, are favoured as “good”. Fait Muedini concludes that “many Sufi and non-Sufi Muslim groups are not only willing to help [fight terrorism] but have been taking up this cause for years.”

Yet certain groups of Sufis have exhibited a quite wide range of behaviour and practise. One such group is Ismaili Muslims. One of the largest offshoots in Shi’ism, Ismailism emerged during early days of Islam, reaching its peak of influence in Iran in the 11th century and Egypt under Fatimid dynasty in 10-12th centuries. The Ismaili leader Hassan Al-Sabbah designed various methods of assassination of its enemies; even the word ‘assassin’ derived from Ismaili practice related to hashish consumption. However, over centuries it evolved into a different kind of practice. The current leader of Ismailis, Aga Khan IV, radically transformed the branch, emphasizing education, and humanitarian aid. The Aga Khan Foundation has earned a highly positive reputation around the globe for its assistance in eradicating poverty and promoting culture.

The historian Bernard Lewis in The Assassins writes that in the course of its evolution, Ismailism “has meant different things at different times and places”. Ismailism manifested a remarkable ability to adapt to different conditions. Perhaps, the enlightened reformation in Ismailism which happened under Aga Khan IV’s leadership is the brightest example of possibility for political Islam to become an engine driving progress and education. At present, however, the scope of Ismailism’s influence is quite limited to only certain geography within the Islamic world, especially due its Shia nature.

Other branches of Sufi Islam emanated from Sunni traditions and have a similar potential for enlightenment, for example, Nursism was employed by the Turkish cleric Fatullah Gulen for the advancement of education and technology. Gulen, unfortunately, turned his group into a semi-secretive political network and fought for obtaining political power in Turkey and other neighboring countries. In 2016 the Turkish government accused the Gulen movement of attempt to stage coup d’etat in the country and arrested thousands of followers. With this purge of its most influential adherents, it appears as if the Gulen movement has missed its opportunity to influence either the country of Sunni Islam.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Sufism has come under increasing attacks from Islamic governments and clerics alike. While in previous centuries, Sufism had played a prominent role in the struggle for the revival of Islam and, occasionally, against Western colonization, today it is associated in many Muslim countries more and more as a heresy vis-a-vis “pure” Salafi Muslims.

This analysis is just an attempt to reflect on the potential of Sufism as an alternative to radical political Islamism. Any potential for Sufi influence is probably already gone. In any case, Sufism should not be regarded as a panacea for political Islamism. After all, if ordinary Muslims are strongly discontented with their societies’ pandemic corruption, economic stagnation and political chaos, Sufism alone is not the cure, or where they will look for change. This is can be seen in Northern African countries where moderate governments make efforts to support Sufism, but an increasing number of devote Muslims still become radicalized. Further, not all Sufi leaders demonstrate the most positive features associated with their sect; some of them tried to hold authoritarian grip on communities, for example in South Asia.

What is clear is that the eradication of extremists and radicals who have hijacked Islam and the religious agenda in general, requires not only law-enforcement measures but the efforts of enlightened clerics supported by government reforms and, most importantly, the end of foreign occupation and domination of Muslim countries.

As colonialism was the principal reason for the radicalization of Islam and clerics rejecting liberalism and democracy, if the West stop its military adventures in the Middle East, and permit the people to sort things out themselves, it might cause some short-term instability – which hardly could be worse than the situation we find ourselves in now – but let Islamic followers to rediscover its enlightened (Westerners like it calling “moderate”) traditions.

*Farid Shafiyev, is a historian from Azerbaijan.