Lives Of The Saint: C.S. Lewis On Stage And Screen – OpEd

Why has the life of this Oxford don, Christian apologist, and storyteller proved so seductive to filmmakers and playwrights? Perhaps because his life was a great story itself.

By Peter Tonguette

Sometimes it seems as though the only things that exercise modern souls are sex, scandal, and sin, but all around us, every day, there are indications that a not-insignificant portion of the population seeks something more. These strivers and seekers are not looking for men whose flaws make them relatable but heroes whose virtues make them worth emulating.

Even as millions of Americans track the comings and goings of the Kardashians or Chrisleys, millions more tune into YouTube to watch the lectures of Jordan Peterson; study the “Stockdale Paradox,” named for the stoic ethos of Admiral James Stockdale; or follow the Instagram account that preserves the sharp but generous correspondence of Stephen Sondheim to his many admirers.

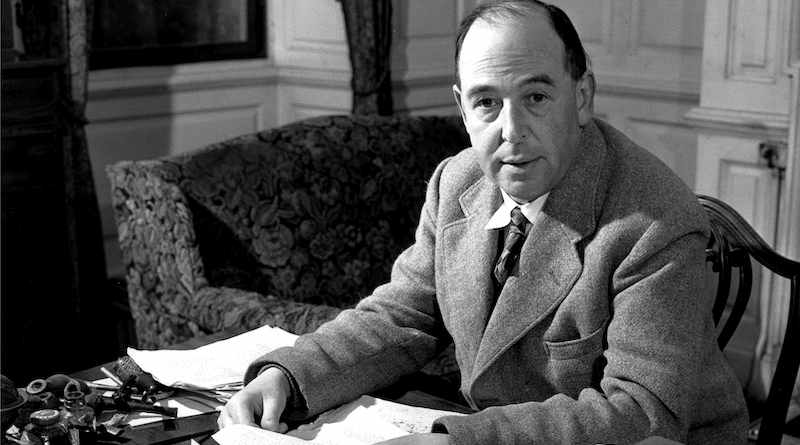

If anyone still doubts that the public has an appetite for stories of great men overcoming obstacles and thereby conveying eternal truths, consider what can only be called the theatrical and cinematic afterlife of British writer and Christian apologist C.S. Lewis, who died in 1963 but for decades since has lived on in countless fictionalized incarnations on stage and screen. Actor David Payne has presented one-man shows under the titles An Evening with C.S. Lewis and C.S. Lewis: My Life’s Journey, and playwright Mark St. Germain took a book about Lewis and Sigmund Freud, The Question of God, and wrested from it an acclaimed off-Broadway play, Freud’s Last Session(soon itself to be a film). Just last year came yet another film about Lewis’ religious life, The Most Reluctant Convert.

Above all, there is William Nicholson’s stunning Shadowlands, which dramatized the most consequential episode of Lewis’s personal life—his relationship with Joy Gresham, a Jewish woman from New York whose role shifted from correspondent to intellectual compatriot, friend, and finally spouse—first into a 1986 television film, then a play, and, most gloriously, a 1993 film starring Anthony Hopkins as Lewis and Debra Winger as Gresham. The ’93 film, directed by Richard Attenborough, was released earlier this fall in a new Blu-ray edition that makes its physical landscape—at one point the story takes Lewis and Gresham to the “Golden Valley” in Hertfordshire, England—as majestic as its spiritual terrain.

Of course, Lewis does not need to be played by an actor or mouth words dreamed up by a scriptwriter to sustain his influence. Born in Belfast, Ireland, on this day in 1898, Lewis was assured a place in literary and moral history on the strength of his remarkable writings, including the Narnia books for children (the authentically magical The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and its equally fantastical sequels), as well as his widely beloved contributions to Christian apologetics, including The Problem of Pain and Mere Christianity.

Yet it is no overstatement to say that it has been the years since Lewis’ death—the years during which he has emerged as a grandfatherly purveyor of wisdom and incubator of grace through the performances of Hopkins and others—that he has emerged most decisively as a man on whom to model oneself. In terms of sheer numbers, such is the nature of mass culture: More people are likelier to stream Shadowlands or call up a YouTube performance by Payne (C.S. Lewis: My Life’s Journey has 2.4 million views on the website so far) than read a decades-old book of essays.

Happily, since nearly all fictionalized depictions of Lewis are sympathetic and most are of genuinely high quality, this is not an occasion for despair. Lewis, who during his own lifetime marshaled the radio airwaves to speak on behalf of Christianity, would surely have wanted his message to reach as many as possible in whatever manner most practical.

Not that Lewis could have imagined that his relationship with Gresham—nor his agonizing response to her death from bone cancer—would ever become grist for the public mill. Lewis’ classic book-length account of his long slog through mourning, A Grief Observed, was issued under the pseudonym N.W. Clerk in 1961; its actual author was not made known to the world until after his own death.

As Gresham’s son from her marriage to novelist William Lindsay Gresham, Douglas Gresham, explained in an introduction to A Grief Observed, his mother and stepfather were wayfaring types who settled on Christianity after cycling through other ways of comprehending the world (including, in Gresham’s case, atheism and communism). In fact, that spirit of intellectual adventure helped direct them to each other when Gresham, estranged and then divorced from her husband, engaged Lewis by letter and then face to face—a surprise, certainly to him.

“I think that Jack resisted the deep emotional attachment to my mother which he began to be aware of, largely because it was something which he mistakenly thought was alien to his nature,” Douglas Gresham wrote. “Their friendship on a platonic level was convenient and caused no ripples on the placid surface of his existence. However, he was forced not merely to inward awareness of his love for her, but also to public acknowledgement of it by the sudden realization that he was about to lose her.” The couple married in a civil ceremony (primarily to keep Gresham from being deported to America) in April 1956. But once Gresham received her cancer diagnosis, not even a year later, Lewis demanded that the marriage be solemnized by a Church of England vicar at her hospital bedside. Joy died in July 1960.

This is approximately the story relayed in Attenborough’s film version of Shadowlands, which benefits from two performers ideally suited to their parts: Hopkins begins the film as crisply confident, as we imagine the pre-marriage Lewis to have been—he speaks sharply before great crowds about the way that God uses suffering to hone us, his children—but softens, a bit at a time, through the penetrating, relentless, maternal presence of the great Winger, who captures what Lewis, in A Grief Observed, said of the woman he called “H.”: “Her mind was lithe and quick and muscular as a leopard. Passion, tenderness, and pain were all equally unable to disarm it.” In cinematic terms, the movie belongs to the stiff-upper-lip romance epitomized by David Lean’s Brief Encounter: Hopkins and Winger—neither svelte, he rather staid, she somewhat haggard, both certainly middle-aged—dance around the topic of their growing affection for each other and never really say it aloud until they suddenly find themselves exchanging vows.

Here is the film’s first lesson to anyone who cares to hear it: You can live a life of boring contentment for years and years—Lewis is certainly at home jousting with colleagues and sharing household duties with his brother, Warnie (in Shadowlands played by Edward Hardwicke)—but, late in the game, find yourself nevertheless jostled awake. Just as Christianity welcomes all, Eros is available to any two people who wish to find it together. You can be a bookworm, or a divorcée, or otherwise flawed or messed up—and still be entitled to companionship and ardor.

The film’s second lesson is more difficult but equally valuable: A death in the family, to use the memorable phrase of James Agee, will make God seem as remote as the lost loved one herself, as Lewis wrote in A Grief Observed. “Why is He so present a commander in our time of prosperity, and so very absent a help in time of trouble?” Hopkins’ line after Gresham’s death—“God knows, but does God care?”—expresses the same sentiment. In A Grief Observed, and in Shadowlands, Lewis powers through this period of honest doubt to a restoration of faith. “Praise in due order; of Him as the giver, of her as the gift,” he wrote. That the film admits doubt but affirms faith makes it accessible to a generation raised far from dogma.

Surely Attenborough’s Shadowlands does not capture every facet of Lewis and Gresham’s relationship, nor does it reflect the depth of angst expressed in A Grief Observed. But this splendid film gets the big things right, and by necessity ours is an age in which the lives of the saints are likely to be encountered, when they are encountered at all, on screens of various shapes and sizes rather than between book covers.

*About the author: Peter Tonguette is a frequent contributor to The Wall Street Journal, National Review, and the Washington Examiner.

Source: This article was published by the Acton Institute