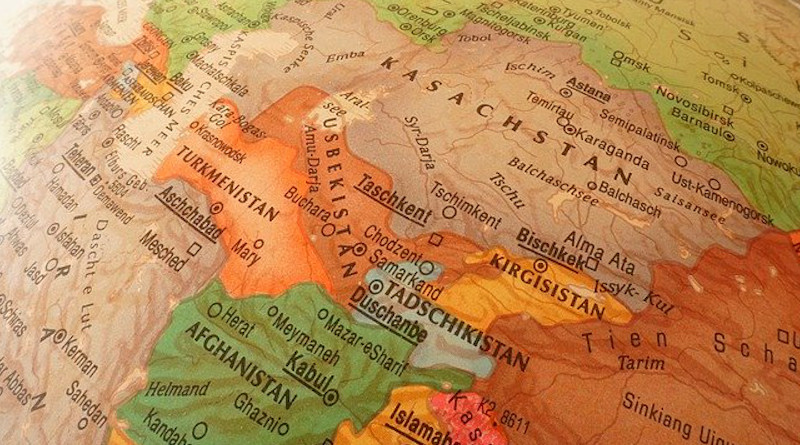

Central Asia Needs A Plan B For Transport And Trade – Analysis

By James Durso

The Russia-Ukraine conflict has highlighted Central Asia’s need for reliable trade and transport routes to the South.

In recent decades, unrest in Afghanistan since 1979, and the sanction-enforced isolation of Iran, have caused the republics to rely on Soviet-era routes North to Russia, emerging links to the West that cross the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus, or to the East as part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

A combination of local initiatives, coupled with a desire to avoid links via Russia that may be hit with sanctions, may accelerate actions to secure redundant southern trade and transport routes.

In January, India’s president, Narendra Modi, hosted a virtual India-Central Asia summit with the presidents of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. The conference covered trade and connectivity issues, cultural exchanges, and security cooperation, among others, and followed the December 2021 signing of nine agreements in areas such as renewable energy, digital technologies, cyber security, and community development projects.

In an apparent conflict, in July 2021 Uzbekistan hosted a conference on connecting Central Asia and South Asia, and has prioritized transport through Pakistan to the ports of Gwadar and Karachi over routes through Iran to the port of Bandar Abbas. Later that month, Pakistan and Uzbekistan signed a transit trade agreement that “would give access of Pakistani seaports to Uzbekistan and offer access to all five Central Asian States for Pakistani exports.”

But, just to be sure, in August 2021 Delhi and Tashkent signed 98 trade and investment agreements that may yield up to $2.3 billion.

Russia is Uzbekistan’s top trade partner, and host to over three million Uzbek guest workers who contribute 12% of the country’s GDP. But Tashkent and its Central Asian neighbors, all of whom rely on remittances from guest workers in Russia, may now view Russia as a source of instability and start to hedge their bets on the Northern neighbor.

Securing a trade route to Central Asia has been a longtime goal of Pakistan, a matter that acquired urgency after the country’s cotton crop failed in 1994. Now that it is almost in hand, and needed more than ever due to the Russia-Ukraine war, will Islamabad’s project be upended by the looming no-confidence vote on the Imran Khan government?

Despite the recent, public bonhomie between the leaders of Pakistan and Uzbekistan, Tashkent is likely aware of the potential of Islamabad to weaponize transport links from Central Asia against India to bolster its policy of “strategic depth” – which will surely disrupt the potential overland Indian-Uzbek trade. In fact, Pakistan removed may doubts when it blocked Indian food aid and medicine shipments to Afghanistan demanding that Pakistani trucks transfer the goods, relenting later to let Afghan trucks move the cargo.

Uzbekistan is a member of the India-Uzbekistan-Iran-Afghanistan Quadrilateral Working Group on the joint use of Iran’s Chabahar port. In early 2021, India proposed that Chabahar Port be part of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), and invited Uzbekistan and Afghanistan to join the multi-lateral corridor project. The INSTC is a 7,200 km multi-modal project that links India, Iran, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Russia, Central Asia and Europe, and this option should be in the back of Pakistan’s mind at all times.

The INSTC may be complicated by U.S. sanctions against India if it pushes ahead with plans for a rupee-ruble exchange mechanism, and arms purchases from Russia. On the other hand, if Washington and Tehran agree to a nuclear deal, the Biden administration will be loath to attack projects Iran pursues, even if its partners are sanctioned governments, i.e., Afghanistan and India.

The Central Asian republics which need new export routes and want to avoid Afghanistan may find Iran’s Chabahar the best option for trade with India with its 1.4 billion person market versus Pakistan’s 212 million, and a per capita GDP which is 2/3 that of India. And cooperation with India’s technology sector will be key to Tashkent’s goal of a 1.6-time increase in per capita GDP by 2026.

Normally isolated Turkmenistan sees Chabahar as a key part of a Eurasian transport route that will include its Caspian Sea port of Turkmenbashi. Iran and Turkmenistan recently discussed expanded trade relations and new arrangements in rail transit, energy, gas and electricity, and maritime transport and are anxious to restore trade to pre-COVID levels.

And Kazakhstan, the biggest economy in the region, is exploring trade via Azerbaijan instead of its usual routes via Russia, may decide that a rail link South via Uzbekistan is an option. The Kazakh-Uzbek rail link was a key part of the Northern Distribution Network that supplied NATO troops in Afghanistan, and may someday connect to Iran’s mooted 2,000 km Five Nations Railway Corridor that will connect Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and China.

Taliban-controlled Afghanistan also seek an Iranian option both for buying and selling and establishing peaceful links with Iran’s government, which will be more active in the regional economy once it has secured access to the $29 billion in overseas banks that has been blocked by sanctions. Afghanistan should try to reinvigorate trade with India, which was worth $1.5 billion annually before the Taliban takeover. One way to do that will be abide by the 2021 India-Afghanistan Preferential Trade Agreement, though Kabul will be challenged by a lack of institutional depth to successfully execute the agreement.

Central Asia may soon be positioned to trade with, and via, Pakistan and India without the worry that trade will rise and fall with relations between New Delhi and Islamabad, or that its historic export routes via Russia will be blocked by the West. Increased trade will raise incomes and proof the republics against undue influence from China, via its BRI, and Russian actions in what Moscow sees as its “sphere of privileged interest.” Increased trade will also benefit Pakistan which unfortunately has to contend with all the attention that comes with being the “largest single-country venue for BRI projects.”

Washington can help improve the local economic picture. It needs to say early and often that it supports increased regional trade; restrain the sanctions dogs lest its messianic zeal blunt local growth and do more to damage America’s image in the region; then, use its votes at the development banks and international financial institutions to help create the organic economic growth that will empower and enrich the region.

It’s been said, “Never let a crisis go to waste.” The Russia-Ukraine way may be a tragedy for Russians and Ukrainians, but it may give a boost to isolated Central Asia’s need for improved links to the outside world.

*James Durso (@james_durso) is a regular commentator on foreign policy and national security matters. Mr. Durso served in the U.S. Navy for 20 years and has worked in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq.