Africa’s Fragile States Are Greatest Climate Change Casualties – Analysis

By Jihad Azour and Abebe Aemro Selassie

Climate change poses grave threats to countries across Africa—but especially fragile and conflict-affected states. As the continent’s leaders converge on Kenya for next week’s African Climate Action Summit, it is vital that they come up with solutions to support these vulnerable countries.

From the Central African Republic to Somalia and Sudan, fragile states suffer more from floods, droughts, storms and other climate-related shocks than other countries, when they have contributed the least to climate change. Each year, three times more people are affected by natural disasters in fragile states than in other countries. Disasters in fragile states displace more than twice the share of the population in other countries.

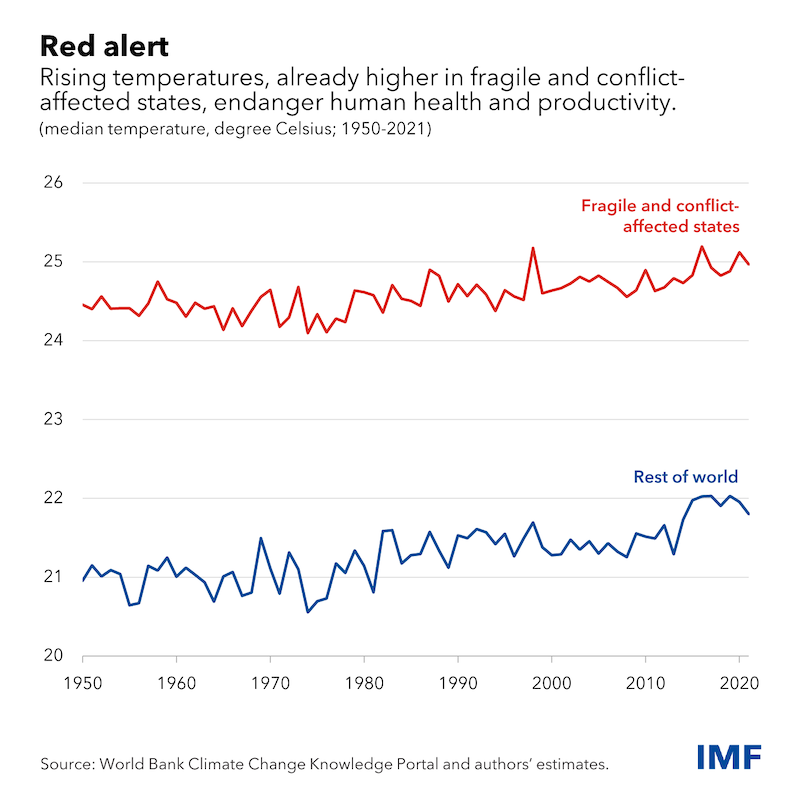

And temperatures in fragile states are already higher than in other countries because of their geographical location. By 2040, fragile states could face 61 days a year of temperatures above 35 degrees Celsius on average—four times more than other countries. Extreme heat, along with the more frequent extreme weather events that come with it, will endanger human health and hurt productivity and jobs in key sectors such as agriculture and construction.

A new IMF paper finds evidence that climate change indeed inflicts more lasting macroeconomic costs in fragile countries. Cumulative losses in gross domestic product reach about 4 percent in fragile states three years after extreme weather events. That compares with around 1 percent in other countries. Droughts in fragile states are expected to cut about 0.2 percentage points from their per-capita GDP growth every year. This means that incomes in fragile states will be falling further behind those in other countries.

The more harmful effect of climate events in fragile states is not only because of their geographical location in hotter parts of the planet, but also because of conflict, dependence on rainfed agriculture, and lower capacity to manage risks.

Conflict undermines the capacity of fragile states to manage climate risks. For example, in Somalia, the areas most severely affected by food insecurity and hunger due to the prolonged drought in 2021-22 were under the control of terrorist groups that thwarted delivery of humanitarian assistance.

Conflict and hunger

Climate shocks also worsen underlying fragilities, such as conflict and hunger, further exacerbating the effect they have on the economy and people’s wellbeing. Our estimatesindicate that in a high emissions scenario, and all else equal, deaths from conflict as a share of the population could increase by close to 10 percent in fragile countries by 2060. Climate change would also push an additional 50 million people in fragile states into hunger by 2060.

The higher losses from climate events also reflect the dependence of fragile states on rainfed agriculture. Agriculture represents close to one-quarter of economic output in fragile states, but only 3 percent of cultivated areas are irrigated with canals, reservoirs, and the like. Rainfed farms are especially vulnerable to droughts and floods. Where irrigation infrastructure does exist, it is often poorly designed, left to crumble, or damaged by conflict.

In central Mali, for example, floods along the Niger river are partly caused by farmers fleeing fighting and drainage ditches falling into disrepair. Sudan’s Gezira irrigation scheme once covered 8,000 square kilometers of fecund farmland but has shrunk to less than half that area owing to poor maintenance.

Finally, the higher losses from climate shocks are also because of the lack of financial means. With the financing needed for climate adaptation well beyond what fragile and conflict-affected countries can afford on their own, sizable and sustained support from international development partners—both concessional financing and capacity development—is urgent to avoid worsening hunger and conflict that can fuel forced displacement and migration.

Policy considerations

For policymakers in these countries, critical interventions include policies to facilitate immediate response to climate shocks, such as building buffers through more domestic revenues, lower public debt and deficits, and higher international reserves. The paper indeed finds that fragile countries with such buffers see a faster recovery from extreme weather events. Strengthening social safety nets and leveraging insurance schemes are also key to financing recovery in the case of catastrophic events. In addition, fragile countries need to implement policies to build climate resilience over time, including scaling up climate-resilient infrastructure investments.

The IMF is stepping up support to fragile states dealing with climate challenges through carefully designed policy advice, financial assistance, and capacity development. Ourstrategy promotes a deeper understanding of the drivers of fragility, tailoring of programs, scaling up capacity development, and synergies with other partners that work in these countries. We are also providing financial support through standard facilities, emergency financing and, more recently, our new Resilience and Sustainability Facility.

These efforts by the IMF and other ongoing initiatives by international partners are still a drop in the big effort needed across the entire international community to protect the most vulnerable. The Africa Climate Summit could be a step forward towards generating effective solutions for mitigating the devastating impact of natural disasters and droughts on the continent’s people and economies.

—This article reflects research contributions by Laura Jaramillo, Aliona Cebotari, Yoro Diallo, Rhea Gupta, Yugo Koshima, Chandana Kularatne, Daniel Jeong Dae Lee, Sidra Rehman, Kalin Tintchev, and Fang Yang.

About the authors:

- Jihad Azour is the Director of the Middle East and Central Asia Department at the International Monetary Fund where he oversees the Fund’s work in the Middle East, North Africa, Central Asia and Caucasus.

- Abebe Aemro Selassie is the Director of the IMF’s African Department. Previously, he was deputy director of this department. At the IMF he has led the teams working on Portugal and South Africa, as well as the Regional Economic Outlook for sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: This article was published by IMF Blog