KNB Ex-Head: Ancestors Said, ‘If You Have A Russian Friend, You Should Keep Axe Handy’: Have Chinese Something Similar? – OpEd

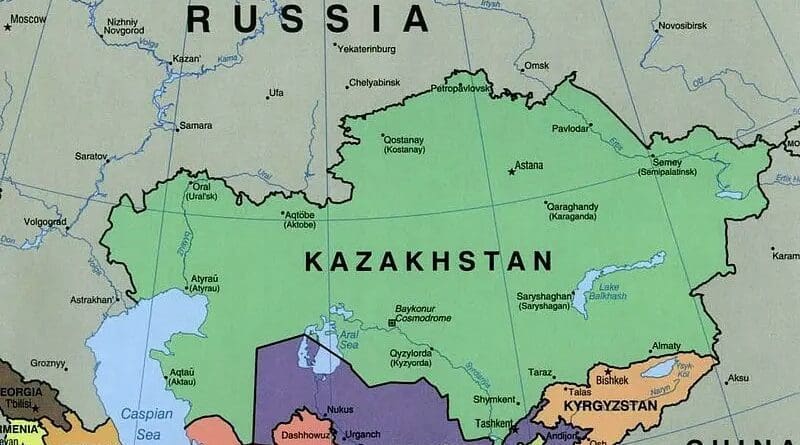

The article by this author entitled, “Incident In Astrakhan: How Much Has Treatment Of Chinese By Russian Authorities Changed Since Blagoveshchensk Massacre? – OpEd,” was published on the site of the Eurasia Review journal early in the morning (by East Eurasia time) of August 9. And it was about the Chinese tourists who had tried in vain to cross the border from the Atyrau province of Kazakhstan into the Russian Federation at the Karauzek border checkpoint in the Astrakhan province of Russia and the impact of that incident.

Later that day and the next day, there was a number of notable developments, one way or another related to that incident or to what had been said in the above article that have left mixed impressions. They seem to be so noteworthy that deserve to be commented on. So, let’s talk about everything in order. First, later on that day, 9 August, a spokesman for the Russian Foreign Ministry told journalists about the official Russian assessment of the Astrakhan incident and the impact it was having in the global media.

Second, on the same day, South China Morning Post published an article by Raffaello Pantucci, a senior associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) in London, entitled ‘China-Russia relations are strong enough to withstand the occasional spat’. The point here is that it proves to be consonant with Moscow’s official position on the Astrakhan incident (it ‘will not affect the relationship between Moscow and Beijing’), not only generally but even by its mere title – ‘China-Russia relations are strong enough to withstand the occasional spat’…

Third, on the next day, August 10, the Kazakh media outlets were full of reports that the Kazakh Prosecutor General’s Office had demanded Russia to extradite a Kazakhstani citizen, Maxim Yakovchenko, accused of inciting racial hatred and separatism. And, as it turns out, Kazakhstan sent the Russian Federation a formal extradition request for him back in March, but it has become known only now. It would seem, what does this have to do with the Astrakhan incident and the impact it has had in the Russian and international media? However, there’s no need to rush to conclusions, as there seems to be reason to suggest that there is a link between the two matters. But we will speak of it later.

Now it’s time for comments on the above subjects in the same order.

1. Russians Apparently Have No One Here But Themselves To Blame

While answering the question of how the refusal to five Chinese citizens to enter Russia across the Russian-Kazakh border at a checkpoint in the Astrakhan province could affect Russian-Chinese relations at a briefing for journalists held in Moscow on the morning of 9 August, Alexey Zaitsev, deputy director of the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Information and press department, noted as follows: “It is obvious that the incident that took place in Astrakhan is out of the political context. I am sure that what happened will in no way affect the general state of bilateral relations. It seems that the hype would play into the hands of our common ill-wishers, who are trying to drive a wedge into the friendship between Russia and China”. He further informed that in connection with the incident close contact is maintained with the Chinese embassy in Moscow, and ‘the official note from the Chinese side, received on August 7, was forwarded to the Border Guard Service of the Federal Security Service (FSB), whose competences include the issues of crossing the state border’.

After that, Alexey Zaitsev, as if to justify, what had happened at the Karauzek border checkpoint, gave this frankly banal argument: “It is quite difficult to completely avoid the emergence of certain issues given the considerable volume and diversity of Russian-Chinese ties”. According to him, ‘nevertheless, all such cases are thoroughly and promptly dealt with by the authorities concerned in a friendly manner’. He next found it necessary to emphasize that ‘Russian-Chinese relations of comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation are at an unprecedentedly high level and are the best in history, which allows us to quickly and effectively address any emerging issues, including those concerning practical cooperation’.

It is clear that the Russian foreign office has now been tasked to take all the necessary measures which ultimately should lead to a recovery of the situation that arose on July 29 in connection with the refusal to five Chinese citizens to enter Russia. But what is being done now in that context by the Russian side just seems like attempts to keep a good mine at bad game.

In a press release published on 4 August, the Chinese Embassy in Moscow informed that it had asked Russian authorities to look further into excessiveness in the behavior of Russian border control inspectors and to give China an honest answer.

They made it very clear what they needed to hear. They repeatedly asked for an explanation with respect to the behavior of Russian border control inspectors in dealing with those five Chinese tourists.

The Russian officials and media continued, as if not understanding what was said to them, to assert that grounds for refusing entry to Russia were that the actual destination did not match that on the Chinese citizens’ visas, in violation of Russian law. According to Alexey Zaitsev, on August 7, the Chinese embassy has already presented the official note demanding, presumably, that very explanation. This seems to be exactly what the Chinese diplomats were (and probably still are) asking from the beginning.

It is not known whether the Russian authorities have as of now provided a ‘satisfactory’ response to it or not. Such response should presumably include recognition of the Russian border officers having been excessively brutal with these Chinese tourists. The further consideration of the Astrakhan incident has probably been transferred to a non-public plane. No other official information has been released since 9 August. As for Mr. Zaitsev’s above statements on this subject, they not only have not clear things up, but they have also given rise to new questions about the Astrakhan incident and its impact.

According to him, it ‘is obvious that the incident that took place in Astrakhan is out of the political context’. Perhaps things might have been so, had the Russian authorities apologized for the actions of their border officers in the instance under consideration after the first request by the Chinese embassy. Instead, Russian officials in Moscow have begun to justify those border officers’ decision to refuse entry to those Chinese tourists and by default the border control inspectors’ actions. Only then has the Chinese side made this story public. The Russian officials apparently have no one here but themselves to blame. As to his finding that ‘the hype would play into the hands of our common ill-wishers, who are trying to drive a wedge into the friendship between Russia and China’, it gives way to doubts, too.

Here is what the Times of India, a newspaper which can hardly be suspected of being biased to Russia, writes about that incident and its impact: “Video footage widely circulated on Chinese social media platforms over the weekend showed Russian border officials going through suitcases, with one of the travelers saying he felt like he was being treated as a criminal… A hashtag on China’s response to the incident saw nearly 50 million views on the Twitter-like Weibo platform, at one point ranking among the top ten most searched topics. Videos posted by social media accounts run by party-backed outlets such as Beijing Youth Daily primarily focused on the mistreatment of the travelers, echoing parts of the embassy statement that such behavior isn’t in line with China and Russia’s “current friendly situation” and “the trend of increasingly close exchanges between people’. Some of the most upvoted comments on Weibo questioned whether the travelers had failed to give a bribe, while others cautioned against having diplomatic relations with Moscow. “It goes without saying that one cannot have a deep friendship with Russia,” said Weibo user “Wall-E_22,” in a post that received almost 1,000 likes”.

This is a vision of the Astrakhan incident and its impact by quite an unbiased observer. The focus herein is on the Chinese side indignant reactions to ‘the mistreatment of the travelers’ from China by Russian officials. There is almost no comment there on the fact of them having been denied entering to Russia. In the view of Chinese officials and multi-million audience of China, the discriminatory treatment of tourists from China is a primary aspect of the incident that took place in Astrakhan. Should Moscow admit this, this it would have to create a precedent of punishing white Russians for the way they are commonly used to treat [East] Asians. Maybe it cannot afford to do that.

The usual practice in Russia is that in almost every conflict, related to discrimination on the basis of race, the Russian authorities, judging by facts, take the side of Slavic white supremacists and are often prone to shift the blame on those who have been harmed by them. The majority of ethnic Russian citizens – both ordinary people and public servants – in Russia seem to be tended to take this for granted. Moscow TV and its celebrities, Russian MPs and high-ranking officials have been and are promoting frankly contemptuous attitude to people having Asian facial features. In the spring of 2021, when US president Joe Biden went to Atlanta for the purpose of meeting with Asian-American leaders and condemning the rising violence against their community after six Asian women were shot dead in the US state of Georgia, and the UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres issued a statement expressing his profound concern over the rise in violence against Asians, and people of Asian descent, Russian FM spoke against the aggression towards white people, white US citizens and warned that anti-white racism might be building in America. Thus, Sergey Lavrov kind of expressed his and the Russian leadership’s ‘fi’ to what had been a matter of concern for Joe Biden and Antonio Guterres and made it quite clear that Asian lives, whether in the West or Russia itself, didn’t matter to him and official Moscow, and that the only thing that matters to them was white lives all over the world. Against such a background, what can be expected from ordinary Russians, common people and public servants, who live in an out-of-the-way place, rarely see non-post-Soviet foreigners, but attentively listen to what the Russian high-ranking officials, like Lavrov and Vladimir Medinsky (Kremlin aide), and Moscow TV celebrities, like Boris Korchevnikov and Anfisa Chekhova are saying?!

The problem of the non-understanding by many from far abroad of what happened in Astrakhan, can probably be also explained by the fact that the ethnic Russians living in that Russian province, closed in on one side by Kalmykia, a Russian autonomous republic, and on the other by Kazakhstan, have apparently become so accustomed to behave arrogantly with the surrounding people of [East] Asian origin, that it seems that they tend to see this as a norm of life and to be kind of surprised if someone from among of them gets indignant about this treatment. Here’s just one example that can explain a lot.

2. This Is Not The First Time Such Thing Happened

In November last year, Angelina Radchenko, CEO of the Astrakhan 24 TV channel, was, as was said, sacked due to her racist statements. This was reported by Alexander Khinshtein, a State Duma deputy, in his Telegram channel. In doing so, Russian MP cited information he had received from the governor of the Astrakhan province. Such a nuisance happened to the Astrakhan 24 TV channel’s CEO, after she had placed a post on VKontakte with words describing Kalmyk women in ways which give grounds to speak of racism. There is nothing unusual here; this is quite a common practice throughout the Russian society to refer to Kalmyks and all those of their kind (Kazakhs, Buryats, Tuvans etc) as ‘churkas’ (‘die Untermenschen’, ‘the representatives of the inferior races’) and ‘people with squint eyes’.

Angelina Radchenko wouldn’t have been dismissed if Alexander Khinshtein hadn’t stepped in. This is a very rare, if not the only, case of punishment for obvious verbal racist abuse in Russia. It certainly wouldn’t have happened, if the Ukraine war, in which ‘the Buryats, Kalmyks, Tuvans and other marginalized minorities’ are being ‘used as cannon fodder’, had not taken place. Similar verbal abuses by Moscow TV celebrities, Boris Korchevnikov and Anfisa Chekhova, towards Kalmyk men and Buryat women have in no way affected their well-being. There is literally no difference between these three cases.

But it turned out she was the only one who had to be punishable by disqualification from office due to her words described by Alexander Khinshtein as ‘overtly racist and xenophobic’. No one, including Alexander Khinshtein himself, said anything like that about Boris Korchevnikov and Anfisa Chekhova, when they had acted just the same way towards Kalmyk men and Buryat women. So it makes sense that Angelina Radchenko would like to see herself not as a person who has grossly violated certain ethic standards, but rather as a victim of her environment and circumstances, in which, according to Alexander Khinshtein, ‘any attempt to split people along ethnic lines only plays into the hands of the enemy, against whom our guys of various ethnicities are heroically fighting shoulder to shoulder’. Here’s what she said about the whole affair: “My latest post drew a negative network response. In order to blame me for chauvinism, nationalism, one have to have a great a degree of imagination which – fortunately or unfortunately – I don’t possess. If anyone thinks that I wished to humiliate someone, here is my sincere answer – this is not the case”.

As seen above, there are no signs of her feeling she really did something inappropriate, wrong. Angelina Radchenko, most likely, is not ready to see even chauvinism, or nationalism in what Alexander Khinshtein described as a manifestation of racism and xenophobia. She evidently feels confident that in the above case, she didn’t say anything, that wouldn’t reflect that view, which is commonly accepted and expressed pretty much everywhere among ethnic Russians while they are talking about Kalmyks, Buryats, Kazakhs and their likes. She seems to be sure that what she did was nothing out of the ordinary. Here are her own words, as quoted by a24.press: “Yet what I really think is wrong is rocking the situation”. By ‘rocking the situation’ she means the actions of those who widely disseminated her post about the Kalmyks through the media and social networks and ‘twisted it [i.e. its meaning] by their comments’. Angelina Radchenko next pathetically exclaims: “Well, you have achieved a resonance. What is this for? Aren’t you the ones who sow discord?” Her ‘noble indignation’ mostly addresses to the Kalmyks themselves who have been outraged by her post and started to press for action against her. Though this may appear paradoxical, it is not inexplicable. The thing is that many white Russians and other Russian citizens of European or Caucasian origin in Russia are seen to be serenely confident not only in their right to regard people with [East] Asian looks as the representatives of an inferior race and treat them as such, but also in them being quite habituated to their place at the bottom of racial hierarchies in the Russian Federation and, therefore, ready to consider themselves racially inferior to all other people in the country. That is, Angelina Radchenko, former press secretary of the Astrakhan provincial government, apparently realizing that in this case, the Russian authorities’ and Russian majority’s sympathies are with her, seems to be saying to Kalmyks: “Know your place!”.

Commenting on this case, some ethnic Russians say: “That is a kind of Astrakhan humor, and there is nothing wrong with it” and “It’s just a joke, and there’s neither incitement to enmity, nor insults there”. The Astrakhan provincial power, too, seems to have done everything possible to cushion the blow for Angelina Radchenko in conditions when she had been accused of racism and xenophobia by a reputable member of the State Duma. In November, 2022, CEO of the Astrakhan 24 TV channel wasn’t dismissed even at least with the wording ‘due to ethical violations’, though the Russian media then reported that she had been sacked due to her racist statements. The truth is that she wasn’t fired – she ‘resigned on her own free will’.

The provincial authorities reported with much pomp about her dismissal as if it had occurred as a result of their formal decision. As to the demand of the public in Kalmykia for Radchenko to be held accountable for exciting hatred or hostility, as well as humiliating human dignity under article 282 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, it just fell on deaf ears in Moscow and Astrakhan. So, the whole thing regarding the formal measures taken against Angelina Radchenko, seem to be no more than an empty shaking of the air by Russia’s national and regional governance system. The case that had been seen by Russian MP Alexander Khinshtein as a manifestation of racism and xenophobia, was not officially recognized, classified and recorded as such.

3. Why Does Kalmyk Author Liken Contemporary Russia To Nazi Germany?

In that story, as in a drop of water, the true attitude of the Russian authorities and society to all people of [East] Asian origin is reflected. And it can help to understand why Moscow’s officials are putting off a response to the Chinese embassy’s request to look into excessiveness in the behavior of Russian border control inspectors and to give China an honest answer. The Russian power appears to be committed to keeping high levels of the Russian-Slavic population’s alienatedness from people of [East] Asian origin in Astrakhan province sandwiched between Kazakhstan and Kalmykia, as well as to maintaining the local Russian Europeans’ belief that they are bound to get its support in case of any disputes or conflicts with those outsiders, regardless of who they are – the Kalmyks and Kazakhs, which the Russians call ‘Kitayezy’ (Chinks) or ‘Korsaki’ ( Steppe Foxes), or the Chinese proper.

Kalmyks, as the only Mongolic ethnic group living mainly in European part of Russia, seem to be particularly exposed to racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and intolerance in the Russian Federation. So, it is hardly surprising that Erzhen Erdeni, a Kalmyk female author, while reminiscing about Asia-phobic abuse like a ‘Kitayeza’ (a Chink), or ‘Slant-eyed one’ she had heard, and referring to racism that Hannah Arendt, a German-born American historian and political philosopher, had faced as a child in Hitlerite Germany, said the following: “While living, almost a hundred years later, in a country that defeated Hitler’s Nazism, I have gotten an absolutely identical experience of going through life”.

Now imagine a group of tourists looking confident from China, known as the second largest economy in the world, arriving at the border of this part of the Russian world, sandwiched between Kazakhstan and Kalmykia. The rest is an already known story, including the way the Russian authorities are trying, just as in the case of Angelina Radchenko, to take the heat off their responsible officials suspected of having discriminated against people of Asian appearance.

4. Two Different Views On The Same Thing

And now, it is time to proceed to considering the article by Raffaello Pantucci published in South China Morning Post, 9 August 2023. Obviously, the author here is seeing his key task in substantiating his own thesis that those interpreting ‘a rebuke of Moscow by Beijing’ over the Astrakhan incident as a shift by China away from Russia are ‘manifestly’ wrong. But this is not about that point of view itself, it is about the arguments which the author brings forward in support of his thesis.

“Such misunderstanding is the foundation of bad policy choices. There is no doubt, Beijing and Moscow have disagreements, but what international partnership doesn’t?” he asks rhetorically.

Later on Raffaello Pantucci adds: “There is no doubt that Moscow and Beijing are in lockstep at a geostrategic level – in many ways similar to what we see in the West, where partners are constantly reaffirming their determination to support Ukraine and confront authoritarians”.

The ways he qualifies the Astrakhan incident and its impact (‘minor disagreements’, ‘the occasional spat’) and kind of likens the China-Russia partnership to the Western alliance seem to be quite in line with what the Russian side would want the rest of the world, including the Chinese, to perceive them.

“The incident with the Chinese tourists, I wouldn’t say that it’s so important”, Oleg Ignatov, the Crisis Group’s senior analyst for Russia, told Newsweek when speaking about the recent border spat between official Moscow and official Beijing. “China is, of course, an ally. It’s a very important partner for Russia. It is a strategic partner”.

But it is one thing to look at all this from a European observer’s perspective, and another thing to look at it through the eyes of a Chinese, or another Asian. Here is what Yuan Jiang, an independent scholar, and a Mandarin and Russian speaker, says on this score in his piece entitled and ‘Chinese citizens’ mistreatment a reminder Sino-Russian ties aren’t all wine and roses’ and published also there, in South China Morning Post, 17 August, 2023: “When five Chinese citizens were unfairly treated at the Russian border late last month, the Chinese embassy in Russia took the unusual step of publicly lashing out at Moscow. China-Russia relations are no longer what they were a few years ago. The shift in the Sino-Russian relationship after Russian President Vladimir Putin’s clumsy aggression against Ukraine has made Beijing more willing to give voice to its displeasure, echoing the Chinese people’s outrage against Russia’s treatment of their compatriots”. This does not, as can be seen, coincide with the way Raffaello Pantucci and Oleg Ignatov see the Astrakhan conflict and its impact, as well as the ‘strategic nature of partnership’ between Moscow and Beijing. The key conclusion of Yuan Jiang’s piece reads as follows: “Regardless of how close China and Russia’s governments appear to be publicly, there is long-standing distrust between their peoples behind the scenes. The enduring lack of trust among individuals might look small now, but the geopolitical influence of distrust can be far-reaching”.

Yuan Jiang notes that ‘nothing is more powerful than personal experience’, and recalls the occasion when he, while a master’s degree student at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations, ‘faced a disheartening situation when seeking to attend China-related lectures’. “Despite obtaining the senior dean’s signed permission, I was rejected repeatedly by a Russian sinologist as the professor only wanted local Russian students to participate”, he says. From this Yuan Jiang draws the following conclusion: “In this situation, I believe most Chinese nationals would ask how different this is from the discrimination Chinese people experienced during the “century of humiliation”.

Yuan Jiang, as a person who knows Russian, has to be familiar with sources in Russian describing the way the Russians treated the Chinese (as well as other people of East Asian origin) during the ‘century of humiliation’. And he has probably read (The mass murder of Chinese people: ‘He was shooting unarmed women and children’) the following: “Mugging, robbing a Chinese in broad daylight, killing him was considered to be a trifling matter, something totally unrelated to the notion of sin, like slaughtering a sheep, and the very notion of responsibility for it seemed to be arrant nonsense. In the case of finding a corpse of a ‘Kitayeza’ (a Chink man) somewhere on the road, the ‘good people’ just dragged it aside by the legs and threw it into some [mine] pit, and nothing more than that. It would never occur to anyone to take the trouble of drawing up a protocol and pursuing an investigation on what had happened. No big deal…”

Based on the above, one may assume by analogy with what Yuan Jiang said, that most Chinese nationals, aware of this past, “would ask how different” the Astrakhan incident is “from the discrimination Chinese people experienced during the “century of humiliation”. The Chinese authorities, seeing their main task in definitively ending China’s century of humiliation by having it emerge as one of the greatest powers on Earth and having already achieved a lot in doing so, obviously can no longer tolerate such discrimination as, for example, the case with Jin Wenxin and his fellow travelers. Anyway, Beijing has already showed signs of becoming ‘more willing to give voice to its displeasure, echoing the Chinese people’s outrage against Russia’s treatment of their compatriots’.

This is the main lesson that one can draw from the Astrakhan incident and its impact.

5. What Has Changed Lately?

And this new turn in the policy of China towards Russia, though it is as yet only indicated, seem to be quite important, too, not only to the Russian minorities of [East] Asian origin, but also to the post-Soviet Central Asian nations, such as Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. The latter can be judged by the appearance of new reports about Maxim Yakovchenko in the Kazakhstani media on August 10. What story is that?

Here are some of its details. According to Uralskweek.kz, in spring last year, Maxim Yakovchenko, a native of West Kazakhstan province, had issued the following comment in social networks: “URALSK, PETROPAVLOVSK, PAVLODAR, ETC. SHOULD BE GIVEN TO RUSSIA”. He next had called the Kazakhs ‘monkeys’. In the autumn of that year, he was charged under Penal Code, sections 174 (‘inciting hatred’) and 180 (‘separatism’). Maxim Yakovchenko left for Russia. He was declared wanted and detained on December 1 in Rostov-on-Don. As reported by the press in mid-February this year, Maxim Yakovchenko has been granted refugee status in Russia and can’t be extradited. As they say in Russia, ‘There is no extradition from the Don’. The press service of the department of police of the West Kazakhstan province then said the following: “The extradition of the suspect [Maxim Yakovchenko] will not take place, as he has been granted refugee status in Russia”. There the matter regarding Yakovchenko’s extradition seemed to be dropped.

On August 10, in the aftermath of the Astrakhan incident, there have been many reports with the headlines like ‘The Kazakh Prosecutor General’s Office is demanding Russia to extradite an inhabitant of Uralsk, accused of separatism’. Kazakhstan, as it turns out, sent the Russian Federation a formal extradition request for him back in March. But why is that such a news has become known public only now, almost six months later? What has changed lately? It’s going to be anybody’s guess.

6. Russian expert: Our Guys Will Be Indiscriminately Hitting Kazakhs-Asians By Missiles

Meanwhile, many Russian experts and observers continue to threaten Kazakhstan and ethnic Kazakhs. Here is a quote in that regard from VRUBCOVSKE.RU: “The Kazakhstani army is no match for the AFU [the Armed Forces of Ukraine], so the conflict [of Russia with Kazakhstan] is unlikely to last for a long time. Even more so when it comes to Ukraine, our guys strive not to bomb the local ‘almost’ Russian people with missiles, while [in a war] with Kazakhstan they won’t restrain themselves [that is, they will indiscriminately be bombing and hitting Kazakh-Asians by missiles]” said [Aslan Rubayev [director of the Eurasian problems monitoring center]”.

What this Russian political expert said begs the comparison with the above title content, The mass murder of Chinese people: ‘He was shooting unarmed women and children’, isn’t it?! What more can be said.

The above is a great example of how the Russian expert thought and propaganda work when the question arises of how to treat the neighboring Central Asian country. It’s rather usual for them to easily allow themselves to do with regard to Kazakhstan what they would not do in relation to other post-Soviet countries. Most of the latter have proved themselves able to induce the Russian side to reckon with them. It’s quite another thing when the largest country in Central Asia and its indigenous population are involved. Moscow and those representing it continues to behave with respect to Kazakhstan and ethnic Kazakhs as if the Central Asian State is one of the autonomous republics of Russia and the Russians can freely afford to insult its native population the same way they do this to the ethnic minorities of East Asian origin in the Russian Federation, such as the Buryats, Tuvans, Yakuts, Khakas and Kalmyks. Buryats and Kalmyks, by the way, say that the heads of their autonomous republics are unable to openly defend their peoples.

What do the Kazakh elites think about all this? There is no information what those in formal government positions think on this matter. Some of those people, who are now retired, seem to be more open to conversation on this topic. In one recent interview, the ex-head of the Kazakh KNB (the National Security Committee of Kazakhstan), Amangeldy Shabdarbayev said: “Well, as our ancestors used to say, “In case of having a Russian friend, you should keep your axe handy”. The question is: Is there something similar, retained in the Chinese people’s memory?