Disrupting US-China Relations Will Incur High Costs – Analysis

Efficient production lines, millions of jobs and affordable consumer products of all types depend on stable US-Chinese relations.

By Farok J. Contractor*

Alarm bells are ringing about President Donald Trump’s angry pronouncements against China, calling the nation a “currency manipulator” and threatening tariffs on Chinese imports. Official designation must come from the Treasury Department, and so far, these claims have been backed with little calculation of costs or jobs gained or lost.

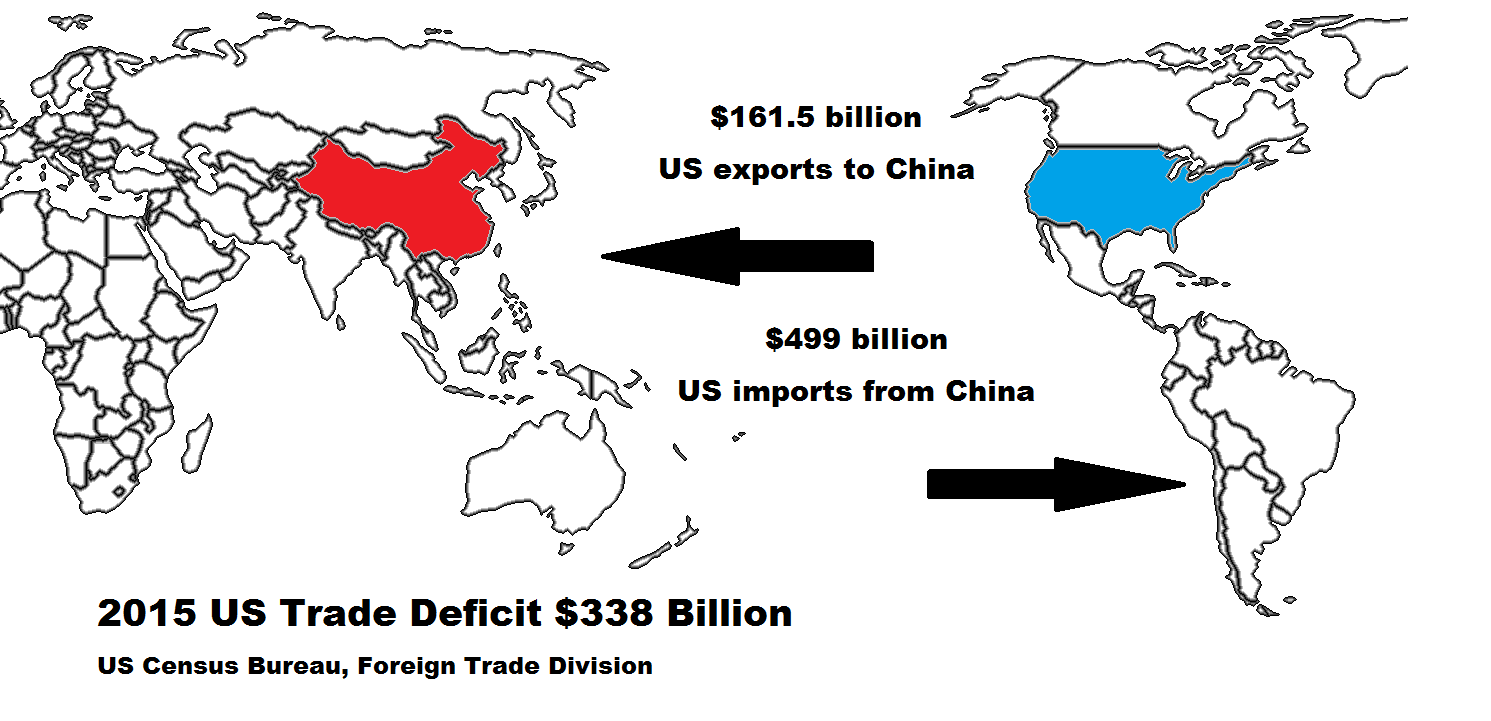

Trump highlights the lopsided trade imbalance between China and the US – a deficit of $338 billion. So China has more to lose, but until 2014 plowed their surpluses back into US government Treasury bonds and securities. US consumers could expect higher prices, and China could retaliate on US-made products and services and sell its $1 trillion-plus investments in US securities – although this would hurt China too, as any attempt to unload large amounts of US securities would immediately reduce the dollar’s value.

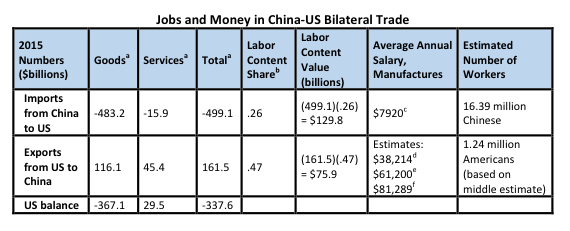

Estimating the numbers of workers involved in US-China trade is a tricky task. Taking data from the World Bank surveys on the “labor share of export value” and inferring from that, the labor content in each country’s exports offers a rough estimate of 16.39 million Chinese workers engaged in exports to the US and 1.24 million American workers engaged in exports to China.

Foreign direct investment: Besides imports, consumers can obtain foreign products through foreign direct investment. A Chinese buying a Buick is not buying a car made in the US, but one made by the Shanghai subsidiary established by General Motors in 1997. An American who purchases a small refrigerator at Walmart is likely buying from Haier, a Chinese company whose US subsidiary, Haier America, Inc., produces refrigerators in South Carolina. Both products include parts imported from other firms along the supply chain, and this is among the many complications in understanding foreign direct investment data.

Chinese FDI in the US accelerated after 2010, according a 2016 report by the National Committee on US-China Relations and the Rhodium Group. By 2015, investment by Chinese companies in US operations had reached an annual level of $15.3 billion – $3.4 billion from Chinese government enterprises and $11.9 billion from presumably privately held Chinese companies.

The value of Chinese acquisitions of American firms was eight times the number of built-from-scratch investments, suggesting a Chinese strategy to gain technological and market knowledge. FDI from most emerging nations has a knowledge-seeking motivation.

Americans need not be alarmed for two reasons: The biggest Chinese investments are in innocuous sectors such as real estate, hospitality, and business services where proprietary technology is not an issue. The largest Chinese investment to date has been in pig farming. Even in sensitive sectors such as computer technology and life sciences, the White House–guided Committee on Foreign Investment has embargoed foreign investment in sectors deemed sensitive or if the intelligence services or Commerce Department indicate danger to competitiveness of American firms.

US firms, as far as FDI is concerned, have more to lose in the event of trade disputes. Chinese FDI in the US in 2015 amounted to $15.3 billion, but US investment in China was almost five times as big, at $74.6 billion. For 2015, there were 6,677 American company affiliates in China compared with around 1,200 Chinese-owned companies in the US.

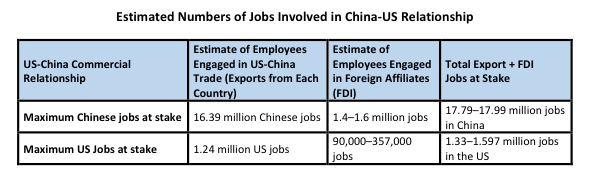

Many more FDI jobs are at stake in China – up to 1.6 million according to Chinese Ministry of Commerce – because of greater use of cheap labor. The Rhodium Group estimates the 1,200 or more Chinese affiliates in the US employ directly around 90,000 Americans. Alternative estimates, including direct as well as indirect employment, suggest between 317,730 and 357,000 US workers connected with Chinese FDI in the US. The US Commerce Department reports that up to 10 million US residents work for foreign companies directly and indirectly, and Chinese FDI represents only about 3.5 percent of FDI in the US.

In sum, with total US employment at 122 million and Chinese employment at 775 million, bilateral-FDI represents a small, albeit significant fraction of overall jobs for either nation.

Adding up the numbers for exports as well as FDI between China and the US, the maximum number of jobs at risk in China is up to 18 million, and in the US it is less than 1.6 million.

Such estimates represent maximum impact on jobs in the worst-case scenarios – and short of a calamitous dispute between the countries, the worst is unlikely to happen. Still, the above estimates give an idea of the numbers of jobs at stake.

Extra costs to US consumers: The United States is one of the few nations that could produce almost everything domestically that it now imports from China – with higher costs for households and hundreds of billions in transition costs for businesses.

US consumers are patriotic, but they also care about their pocketbooks. A Boston Consulting Group report found that more than 80 percent of US respondents said they prefer US-made items and are willing to pay more. But confronted with a tangible choice in an Associated Press survey, only 30 percent preferred US jeans priced at $85 over imported jeans for $50.

Moreover, of every dollar a consumer pays for a Chinese-made product, 55 cents is kept by US businesses for services such as marketing and sales. Only 45 cents goes to the Chinese producer. And only 2.7 percent of US consumer spending overall goes to products made in China, according to the Federal Reserve Bank and other studies. This sounds small, but the calculation works out that the additional cost for US consumers would be about $295 billion in 2016 alone, or $2,380 for each household.

Is re-shoring realistic? In the absence of dire national emergency, US consumers won’t prefer paying additional costs. The $2,380 estimate assumes replacing Chinese imports with US manufacturing. But a more realistic scenario is that if Chinese products were embargoed, production would move to other low-wage nations such as Vietnam or Bangladesh, as is already happening.

In 2015 General Electric’s appliance division tried to “re-shore” manufacturing to the US assuming that automation and productivity could offset higher US wages. But GE encountered another challenge – the parts-supply base for appliance components had disappeared from the US. Chinese parts suppliers are efficient and low-cost. Adding the transport costs of parts shipped from China to US assembly lines, plus management and additional inventory costs, made producing appliances in the US more costly.

In June 2016 GE sold their appliances division to the Chinese company Haier for $5.4 billion. Restoring all elements of the supply chain in the US would require decades and is a theoretical dream.

China’s $2 trillion in US securities: The Chinese government holds $1.3 trillion in US Treasury bonds, and Chinese entities collectively own about $2 trillion in US securities, second only to Japan, not counting the ownership of more than 1,200 US-based companies through FDI. The total may be higher, considering investments through Hong Kong and Caribbean tax havens where owners’ identities are often murky.

In an emergency, the Chinese could precipitously sell their US security holdings, panicking US bond and equity markets, eventually resulting in a plunge in the dollar’s value. But then, the Chinese would receive a lower return. The scenario is unlikely, short of a military confrontation. For the past 25 years, the Chinese government has regarded the US as its principal foreign market.

China has every incentive for keeping the US economy going strong. Simply put, it’s a matter of self-interest. The $2 trillion in investments in US securities do not earn a high return, but the investment is safe. In effect, the holdings demonstrate Chinese support for US-China trade and the global trading system.

While the Chinese may not be thrilled about entanglement with the US economy, both nations have a mutual self-interest. Together, they account for 40 percent of world GDP.

Participation in global trade has created employment for more than 100 million Chinese. The US gains from the relationship with up to 1.6 million jobs that depend on China, $295 billion annually in lower consumer prices, as well as investment in US securities and low interest rates.

Trump may be right in asserting that China has benefited more from the relationship than has the US. But international trade theory and practice never suggest consistent and perfect trade balances. Theory holds that nations are better off by participating in international trade. And his claim that the loss of US jobs is “…the greatest theft in the history of the world,” true only in small part, fails to consider that three out four US jobs have been lost due to automation, information technology and other productivity boosters.

Proposals to return jobs to the US are economically non-viable. Should the US carry out threats to levy a tariff on Chinese products, production is unlikely to return to the US. Other low-wage nations are ready to compete including Vietnam, India or Bangladesh, where hundreds of millions of people work for less than $1 per hour. With rising wages and a shortage of skilled workers, thousands of Chinese factories have already relocated to such low-wage nations. Disruption of global value chains would add hundreds of billions per year to US businesses, increasing prices for US buyers – with extra costs falling disproportionately on lower-income Americans.

The two great nations need each other. They can pursue a relationship that is “bipolar,” fraught with anxiety, or they can continue historic cooperation and lead to develop the 21st-century global economy.

*Farok J. Contractor is a professor in the Management and Global Business Department at Rutgers Business School. He has researched foreign direct investment for three decades and also taught at the Wharton School, Copenhagen Business School, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University, Nanyang Technological University, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade and other schools and conducted executive seminars in the US, Europe, Latin America and Asia. He produces a blog on Unbiased Perspectives on Global Business Issues. An expanded version of this article is in the March 2017 issue of Rutgers Business Review.