Kazakhstan Has A Vested Interest In Afghanistan’s Stability – OpEd

What should be taken into account when analyzing the Kazakh government’s attitude and policies toward Afghanistan?

According to Kazakh media reports, Kazakhstan’s ambassador to Kabul, Alimkhan Esengeldiev, met with the acting foreign minister in the Taliban (insurgent group banned in Kazakhstan) government of Afghanistan, Amir Khan Muttaqi, on September 26th 2021.

During the meeting, the two parties stressed the importance of developing trade between the two countries and stated willingness to expand the bilateral trade cooperation. Alimkhan Esengeldiev expressed his satisfaction with the security situation in the Afghan capital and urged the international community to provide humanitarian aid to Afghanistan.

Amir Khan Muttaqi reiterated the new Afghan authorities’ commitment to establish peaceful relations with all countries, primarily with neighboring states in the region. He also expressed the new government’s determination to prevent the emergence of any security threat from the territory of Afghanistan.

A month and a half after Kabul fell to insurgents, there comes a time when the problems of daily subsistence are coming to the fore once again. Over the last couple of months, marked by the withdrawal of Western military forces and the Taliban takeover, Afghanistan has been facing severe financial constraints due to blocking of the foreign aid flow to the country. The Afghan population suffers a shortage of food supplies. The resumption of food delivery to Afghanistan is, therefore, very important for normalizing the situation in the country. The way things are, Kazakhstan seems to have the highest stake in the restoration of economic stability in Afghanistan.

That’s quite understandable: “For Afghanistan, where power (political control) has recently changed hands, Kazakhstan is the main, if not the only supplier of grain. And the former Soviet republic is, in its turn, heavily dependent on this country. Afghanistan accounts for half of all its grain exports. According to Yevgeny Karabanov, a representative of Kazakhstan’s Grain Union (KGU), approximately 3-3.5 million tons of Kazakh grain have usually been to that country. In addition, Afghan importers have bought flour from Uzbekistan, which is made of Kazakh wheat” (“Kazakhstan would lose buyers which account for 50 per cent of its grain exports” – ROSNG.ru).

The dramatic power shift after the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan and subsequent moves meant to freeze Afghan central bank reserves left Kazakh grain exporters with the need to find new buyers for approximately 3 million tons of wheat. Yet this was a very difficult task, of course. It is therefore not surprising that Nur-Sultan eventually decided there is no sense walking away from the Afghan market. Kazakhstan’s Agriculture Minister Yerbol Karashukeyev said on September 21 that his country would continue exporting wheat and flour to Afghanistan.

The exporting process has recently restarted, the country’s Agriculture Ministry reports. As at 29 September, approximately 200,000 tonnes of flour and 33,000 tonnes of grain have been delivered from Kazakhstan to Afghanistan through Uzbekistan.

As Azat Sultanov, director of the department for production and processing of crop products at the Ministry of Agriculture, said at a briefing, “currently there are no shipment problems”. He described Afghanistan as “a major grain and wheat flour market for Kazakhstan and our strategic partner”.

From the point of view of the Kazakh interests, Afghanistan’s being of a strategic nature is not just a matter of bilateral trade relations. And there’s something else that needs to be taken into account when analyzing Kazakhstan’s attitude and policies toward Afghanistan. These are issues related to the tasks of ensuring the country’s security and promoting access for its products to global markets.

The opinion, expressed by Dauren Abayev, who’s currently the First Deputy Head of the Presidential Administration of Kazakhstan, over two years ago in relation to the first issue, remains of utmost relevance today. At that time speaking in the course of the Open Dialogue television program aired by the Khabar TV, he made a comment regarding the discontent of some Kazakhstanis with the situation in which the state was supposedly providing significant humanitarian support to Afghanistan instead of helping its own citizens in need. In particular he said the following:“Kazakhstan is not the only country rendering assistance to Afghanistan. Today the whole world is seriously concerned about the problems of this country. There is an explanation for it. The international community must assist in providing the necessary environment for the return of normalcy to Afghanistan after decades of armed conflict. Unless that happens, unless the normal life is restored in that war-torn country, the risk of incursions and attacks by extremist forces, the threat of drug trafficking and radicalism will always invisibly hang over us all”.

Dauren Abayev said that in May 2019. A lot has changed in Afghanistan over the last two years. Especially noteworthy are the recent developments in the country. But now the Afghan people, even more than before, needs help “in providing the necessary environment for the return of normalcy”. The awareness of this has led the Kazakh authorities to come up with a proposal for establishing a United Nations logistics hub for delivery of humanitarian aid to Afghanistan in Almaty.

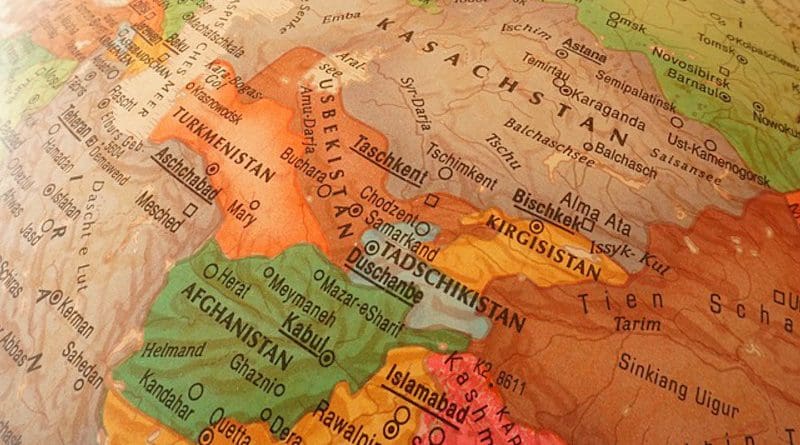

With regard to the issue of ensuring access for the Kazakh products to global markets via Afghanistan, the following can be said. Kazakhstan is a country located mainly in north of Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. This area of Eurasia is a region that is almost furthest away from the world’s oceans and seas. As long as international trade is based essentially on ocean freight, Central Asia will remain on the periphery of the international economic system. Yet that may change owing a deal that Uzbekistan signed with Pakistan in February 2021 to construct a 573-kilometer railway section that would run through Afghanistan and link Termez, the southernmost Uzbek city, with Peshawar, the capital of the Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It would connect the region of Central Asia to ports on the Arabian Sea. It also would signify the implementation of the long-standing idea of linking Central Asia with South Asia. The efforts undertaken by the US last year added new impetus to its implementation.

The New Delhi Times, in an article by Himanshu Sharma entitled “US to link South & Central Asia” (July 20, 2020), said: “The United States and five Central Asian countries pledged to “build economic and trade ties that would connect Central Asia to markets in South Asia and Europe”. Their joint statement in Washington in mid-July called for peaceful resolution of the Afghan situation for greater economic integration of the South and Central Asian regions.

In a trilateral forum in late May, the United States, Afghanistan, and Uzbekistan had reviewed projects to link South and Central Asia for regional prosperity. The joint statement unveiled plans to build railway links between Central Asia and Pakistan and a gas pipeline to India via Pakistan.

Pakistan may have to choose from the two parallel trade routes even though China would definitely expect it to join its economic pact with Iran while the Americans would like Islamabad stay connected to South and Central Asia.

Washington has created a group called C5+1 including the United States, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Another working group will develop the transit potential of Afghanistan, including funding from international financial institutions of large projects”.

In addition to the above, the following comment should be made. On June 30th 2020, the US Secretary of State and the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, the Republic of Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and the Republic of Uzbekistan met in the C5+1 format. Participants in the 6-party forum, as indicated in the joint press statement at the conclusion of the talks, “had a wide-ranging discussion on mutual efforts to build economic resilience and further strengthen security and stability in Central Asia and the region. The participants expressed strong support for efforts to peacefully resolve the situation in Afghanistan and to build economic and trade ties that would connect Central Asia to markets in South Asia and Europe”.

To put it bluntly, this is about the translation into reality of the idea of forming a ‘Greater Central Asia’ through the inclusion of Afghanistan in the group of post-Soviet Central Asian republics. As for specific projects, there are two of them: the building railway links between Central Asia and Pakistan and the laying of a gas pipeline across Afghanistan and Pakistan from Turkmenistan to India. There is nothing new in such plans. The first of them – the construction of a railway line between Central and South Asia – had initially been proposed back in 1993 at a meeting of the leaders of ECO (the Economic Cooperation Organization) member states by then Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif. He said: “The liberation of Afghanistan and the emergence of 6 sovereign states from the former Soviet Union who share common bonds with us provide for a basis of a new relationship which could be a catalyst for reshaping the economic life of our region. With an area of 7 million square kilometers and a population of 300 million, E.C.O. is the second largest economic grouping after the E.E.C. It has thus the potential to be a key regional economic grouping and it already has plans to establish multi faceted cooperation under its auspices. A good beginning has already been made with the development of road, rail and air links. In fact, Pakistan sees its own network of road links eventually linking up for trade with the E.C.O. countries, a linkage which will be important in Pakistan’s quest to enter the 21st century as a modern, progressive and forward-looking country. I have no doubt that the E.C.O. is likely to fulfill its potential as a dynamic and vibrant organization whose people’s skills and considerable potential will help in improving the quality of life of the 300 million people who share a common future and a common destiny based on a better tomorrow. Our purpose here today is to build on existing ties and to create institutions which will facilitate technical, commercial and cultural interaction between the member countries”. His proposal to construct a railway line between Central and South Asia through Afghanistan had failed to gain real support in relevant countries and been shelved. By now, not many people know who first offered such a project. The construction of a railway line between Uzbekistan and Pakistan would provide access for Kazakhstan’s exporting products to the Port of Karachi and the nearby Port Qasim. That’s why the country is very much interested in implementation of this project.

The second one – the routing of a gas pipeline to India via Pakistan – had been accepted for implementation by Bridas Corporation, an independent oil and gas holding company based in Argentina, in 1995. Yet no progress was subsequently made in realizing the project. The Taliban rise to power in Afghanistan. And everything became stalled. Later on, several countries in the region made repeated attempts to give new momentum to this initiative. Nobody seems to mind. Yet there has been little progress so far. This effort is known as the $7.6 billion, 1,814km Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India transnational gas pipeline (TAPI). It would run from Galkynysh, the largest gas field in Turkmenistan, through Afghanistan’s Herat and Kandahar, then Chaman, Quetta and Multan in Pakistan before terminating at Fazilka, India, near the border with Pakistan. The idea of TAPI goes back a quarter century. In 1995, Turkmenistan and Pakistan concluded a memorandum of understanding. The Turkmen government began construction twenty years later in December 2015. At that time Ashgabat announced that the project would be completed in December 2019. Yet it proved to be nothing more than a good intention. The effective implementation is lagging behind the Turkmen government’s promises due to financial problems. At the same time it should be mentioned that outside observers have very little concrete information about the progress of TAPI. The project is, as of now, expected to come on stream in 2023. The Taliban regime is now in place and its spokespersons in Afghanistan have spoken favorably on the TAPI pipeline.

While speaking at the third Summit of Gas Exporting Countries Forum (GECF) held on November 23d 2015 in Tehran, the then Kazakh Foreign Minister Erlan Idrissov stressed Kazakhstan is interested in the main TAPI gas pipeline from Turkmenistan to Afghanistan, Pakistan and India whenever it is built. “Discussions are currently taking place with the Indian side about the possibility of increasing the capacity of the pipeline, taking into account the potential gas supplies from Kazakhstan. Our country is ready to transport up to 3 billion cubic meters annually through this pipeline”, he said. Such a perspective continues to remain quite relevant.

It was reassuring to see that the Americans were trying to give a new impetus to the implementation of old projects. The question that remains is whether they can be implemented at last. There is still no answer to it. But one thing is certain. Pursuing those projects first of all requires efforts to guarantee that there is political stability in Afghanistan.

*Akhas Tazhutov is a political analyst