Western Kazakhstan May Soon Turn Into West’s Achilles’ Heel In Its Confrontation With Russia On Ukrainian Soil – Analysis

Recently, when answering the question whether there would be a war between the Russian Federation and Kazakhstan, well-known Ukrainian journalist Dmitry Gordon said that if Russia had succeeded in taking over Ukraine, it could invade Kazakhstan. “Russia would gladly not [only] fight with Kazakhstan, but [also] enter there and enslave that country. Yet the Russians have no more strength left for it. They do not have the strength to fight two wars [at the same time]. We [really] wore them out”, he noted.

According to Dmitry Gordon, it’s about the idea of restoring the Soviet Union which Putin is obsessed with. The Ukrainian journalist believes that the Kremlin master has all along been obsessed with the mania of restoring the USSR. “Well, if not the entire Soviet Union, then at least part of it – in the form of Russia, Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan united into a single whole”, he added.

“I think that the former Soviet nations have to say a big thank you to Ukraine. Because if it hadn’t been us they would have moved towards you”, Dmitry Gordon concluded.

But does that mean necessarily that this third general war in Europe in the last 100-odd years will not directly affect Kazakhstan in the near future? It’s a very tough question. One that at this point no one can truly answer, only guesswork can be built.

According to one of the most recent media reports on the matter, lately information has surfaced that ‘Russia is preparing a 200,000-strong group beyond the Urals to attack Kazakhstan, so it is not surprising that the Russians began to criticize Kazakhstan for alleged Russophobia’. The implication here is that Russia is going to invade Northern Kazakhstan – because there are many Russian speakers there. I dare say that all this seems to be unconvincing, and here’s why. As things stand at present, such a plan’s hardly what is particularly pertinent for Moscow.

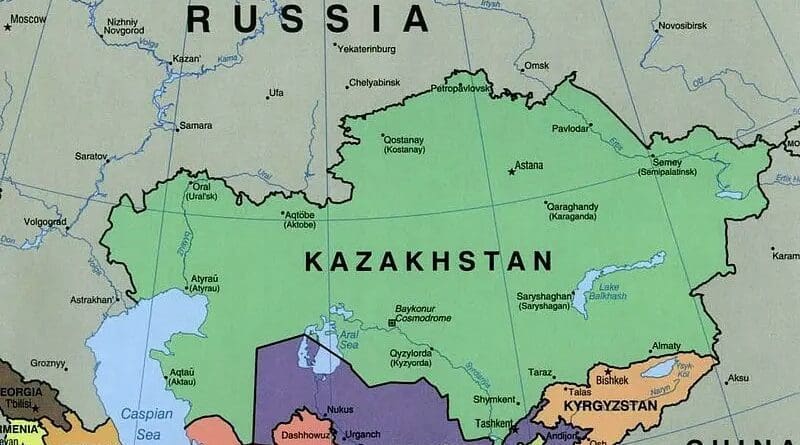

It is quite conceivable that Northern Kazakhstan on its own has been and still is of little interest to Russia. The region can be compared with neither the Donbas that used to be the heart of Ukraine’s industrial economy, nor the Crimean Peninsula on which the Russian Black Sea Fleet is based. In the event of its annexation by Moscow, the Russian Federation would get another depressed and donation-dependent region with the shrinking and aging ethnic Russian (Slavic, European) population, which, besides that, do not already form a majority. Only 18 per cent of the provinces are the donors in Kazakhstan. These are the provinces of Atyrau and Mangystau, the cities of Astana and Almaty. 82 per cent of the provinces are in need of help from the national budget. These include all four provinces of Northern Kazakhstan.

Besides, Russia’s annexation of Northern Kazakhstan, or any part of it, should this occur, would likely be seen by the Islamic world as an open incursion into the Kazakh territory, that is, as an aggression against their fellow Muslims. And there’s one more thing to consider. Should such a move be allowed by Moscow to go, it would involve the risk of causing what was at the time described by Giancarlo Elia Valori, an eminent Italian economist and businessman, as ‘the future destabilization of the Urals and Central Siberia’.

It is obvious, however, that Moscow wouldn’t want to let the situation in Kazakhstan go by chance. The Russians seem to be afraid of this likely turn of events and willing to do anything to prevent it from happening. Shortly before the outbreak of war in Ukraine, Ukraina.ru, in an article entitled ‘Ukraine is not Kazakhstan, that’s why Russia will fight for it [the Republic of Kazakhstan] until the very last’, quoted Andrey Grozin, the head of the Central Asia and Kazakhstan department in the Commonwealth of Independent States Institute, as saying the following: “The problem is that [Kassym-Jomart] Tokayev is being seen as a person who wants to be friends with everyone and is afraid to ruin relations with everyone.

Ukraine, with all its nonsense, is a kind of nuisance, but you can live with it. And Kazakhstan, which is run by Russia’s enemies or is not run by anyone at all (the latter is the most likely one of the bad scenarios), is something, we mustn’t even think about. Should that happen, we will have to deploy not peacekeepers to the [neighboring Central Asian] country, but a real military contingent, in order to take control of the logistics hubs simply so that we retain access to the south [the other four States of Central Asia]. Or else there will be, if you will permit the vulgarism, a complete and total ass.

We will somehow get through with the insane Ukrainian authorities, if not this year, then next. Yet this is just a small piece of geography. [While] Kazakhstan is the ninth largest country in the world in terms of area. There is the 7,500-kilometre (4,750 mi) of unguarded border between them [the Republic of Kazakhstan] and us [the Russian Federation]…

We can’t wall ourselves off from Kazakhstan, even if we wanted to. Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova are countries, which are important to Russia. I mean, in terms of ideology, economy and military potential. As for Kazakhstan, it is different. It is kind of like Ukraine presented in a concentrated form”.

It is important to emphasize in this quotation the words: “Should that happen, we will have to deploy not peacekeepers to the [neighboring Central Asian] country, but a real military contingent, in order to take control of the logistics hubs simply so that we retain access to the south [the other four States of Central Asia]”. The shortest road from Russia to the rest four States of Central Asia runs through the provinces of Atyrau and Mangystau in the western part of Kazakhstan. These are the only two donor provinces in the country. They along with the West Kazakhstan province are also home for the most important logistics hubs. These are also the three Kazakhstani provinces that are most important to the major Western investors (such as Chevron, Eni, BG Group, BP/Statoil, Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell, and TotalEnergies) and the largest European economies (such as Italy, France, Netherlands and Germany).

Well, we can say more. The ultimate prize at stake for the major centers of power, which are considered to be rivals for power and influence in Central Asia, is certainly the relatively sparsely populated territories in the the oil-and-gas-bearing eastern Caspian Sea coast, i.e. Western Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. And although it is not customary to speak out loud about this matter, it has long been not a secret to anyone.

Back in 2002, that is, shortly after the 2001 Western invasion of Afghanistan, American experts in considering the matter of the Central Asian region’s potential attractiveness to America and its allies came to following conclusion: the whole of Central Asia, except coastal areas along the Caspian Sea, is not of long-term interest to the US and the EU in economic terms; and therefore as soon as the NATO withdrawal from Afghanistan is finished, there would be no [economic] reason for them to make significant efforts to preserve and extend their position in Central Asia with the exception being Western Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. Shortly before that, Frédéric Bobin, then Le Monde’s Beijing correspondent, wrote: “According to some Chinese analysts, the American strategy involves separating the Chinese far western provinces – Tibet and Xinjiang – from China itself in order to erect a barrier in the form of ‘mini-states’ that could cut it off from the hydrocarbon wealth” of the Eastern Caspian region (Le Monde, 27 September 2001).

Now, after 20-odd years, the following picture emerges: the NATO forces left Afghanistan. The American strategy has remained incapable of seriously destabilizing the situation in Tibet and Xinjiang, let alone ‘erecting’ there ‘a barrier in the form of ‘mini-states’ that could cut China off from the hydrocarbon wealth’ of the Caspian Sea region. That is, of course, if such a strategy actually exists.

During this period, China has managed to establish a stable supply of oil and gas from the territory of the Caspian region through a network of pipelines – the 1,830km (1,140-mile) long Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan-Kazakhstan-China natural gas pipeline system (known also as Turkmenistan-China gas pipeline) that starts at Turkmen-Uzbek border city Gedaim and runs through central Uzbekistan and southern Kazakhstan before reaching China; and the 2,798km (1,384 miles) long Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline transporting crude from fields located in Western Kazakhstan to the Dushanzi refinery located in the Chinese Xinjiang province.

Through the first one more than 350 billion cubic meters of clean-burning fuel has been transferred to China in 2009-2022. This is a good result. Yet Turkmenistan isn’t going to stop there. Ashgabat has recently unveiled plans to double natural gas exports to China and increase supplies to 65 billion cubic meters per year upon completion of the fourth D string. For comparison: Turkmenistan delivered 34 billion cubic meters of gas to China in 2021. Anyway, Turkmenistan has already become the largest supplier of natural gas to the domestic market of China. And one wouldn’t say the same thing on oil deliveries from Kazakhstan to the Chinese market.

The room to increase supplies via the Kazakhstan-China oil pipeline is limited at around 100,000 b/d. This pipeline has got a capacity of 400,000 b/d, of which 200,000 b/d is being used to import Russian crude under the CNPC-Rosneft deal. And yet, crude supplies from Kazakhstan to China, was at just 90,200 b/d in 2021. This is much less than a tenth of the total that Kazakhstan exports.

The bulk of oil production in the Kazakh republic has been and is being made by TCO (700,000 b/d), NKOK (400,000 b/d) and KPO (226,000 b/d), which are controlled by Western corporations. In March last year, Kazakhstan was producing 1.7 billion barrels per day. It turns out that three main oil fields, Tengiz, Karachaganak, and Kashagan in the Caspian Sea, that are being operated by the American and West European oil and gas giants, account for almost 80% of Kazakhstan’s total crude production. It is therefore hardly surprising that over 70% of Kazakhstan’s oil exports go to the European Union. In other words, Kazakhstan’s oil and gas industry as a whole is mainly working for the EU economy.

Until recently, Moscow did not attach much importance to such division of roles between the Western side and its key military and political ally on the Eurasian continent, Kazakhstan. This was because the Russian Federation itself was then selling large amounts of oil and gas to the West and did not feel bypassed. Besides, over 90% of the Kazakh energy exports went through Russia via the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (53.1 Mt out of 67.6 Mt) and the Atyrau – Samara pipeline (11 Mt) in 2021.

Then the war began in Ukraine, and the Russian oil and gas sector came under sanctions introduced by the US and the EU. In conditions where Putin casts ‘the war in Ukraine as an existential battle with an aggressive and arrogant West, and has said that Russia will use all available means to protect itself and its people against any aggressor’, Russia is quite unlikely to agree to remain merely an operator of pipelines delivering oil from Kazakhstan to the European Union. The Kremlin also can’t ignore the fact that Kazakhstan has decided to proceed with development of the Transcaspian route, and Turkmenistan is gradually being pushed by Turkey and Azerbaijan towards a similar decision.

It can be assumed that in the light of that situation, Moscow may be tempted to contribute to the emergence of ‘something’ in Western Kazakhstan, ‘we mustn’t even think about’. It was said above how Russia might act in the event of such a situation in the neighboring Central Asian country. Should this occur the Kremlin would once again look like a savior, and the West would probably have to seek compromises with Putin on the issues of the Kazakh oil industry, as well as of the war in Ukraine.

Akhas Tazhutov, a political analyst