China Doubles Down On Troubled Pollution Policy – Analysis

By RFA

By Michael Lelyveld

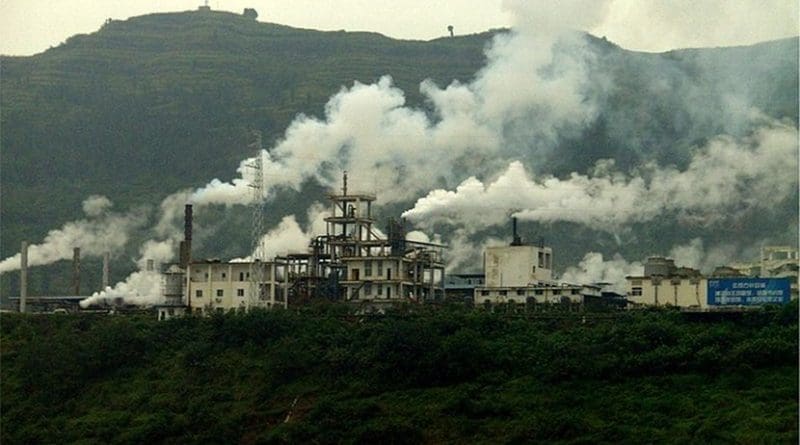

China plans to expand a program of seasonal manufacturing cutbacks to curb air pollution, despite concerns that it may have the opposite effect.

As part of its three-year action plan issued on July 3, the cabinet-level State Council said it would widen the area subject to production cuts from 28 northern cities last winter to 82 cities during the next heating season, Reuters reported.

The program launched in 2017 sought to keep coal-burning factories from adding to smog from coal-fired heating in the region surrounding Beijing.

Last year, producers of steel, aluminum and cement were told to cut output by as much as 50 percent in the affected areas from October to March, Reuters said. The official heating season runs from Nov. 15 to March 15.

The factory restrictions were aimed at avoiding another smog crisis like the one that enveloped Beijing in the winter of 2016-2017.

But last year’s ban on coal-fired heating ordered by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) proved unsuccessful after natural gas projects could not be completed in time. In December, the planning agency was forced to backtrack and allow coal burning to resume.

Problems resurfaced in March when the production limits expired, sparking a surge in output and emissions from steelmakers and other polluting industries.

A review of monthly data from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) shows that crude steel output never declined as manufacturers shifted production to other parts of the country and took advantage of higher prices spurred by fears of the seasonal shutdowns.

In June, the NDRC said inspections of the steel industry in 21 provinces and regions had found “some weak links … including the illegal use of production facilities and illegal addition of new capacity,” the official Xinhua news agency reported.

Coal and gas prices also jumped due to the winter restrictions. Pressure continued into the summer with high electricity demand for air conditioning and growth in industrial production.

The artificial demand created by the seasonal cuts added to China’s energy pressures. Industrial provinces and cities have been warning of power shortages and rationing measures since May.

In the first half of the year, power consumption rose 9.4 percent, the highest rate in at least six years, the National Energy Administration (NEA) reported.

Steel production was up 6 percent after setting monthly production records, according to NBS data.

Coal consumption climbed 3.1 percent during the period, the China National Coal Association (CNCA) and the NEA said.

While the action plan for 2018-2020 would restrict coal use in the 82 localities, it places no new national limits on consumption.

Last year, China burned 50.7 percent of the world’s coal, based on estimates by the BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

The country’s energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions rose 1.6 percent, making China the leading source of greenhouse gases, accounting for 27.6 percent of the global total, the annual review said.

Optics and social consequences

The provisions of the three-year plan suggest that the government is more concerned with the optics and social consequences of urban smog than global warming.

Officials have claimed dramatic gains in air quality as a result of the policy.

In Beijing, the average density of smog-forming particles known as PM2.5 fell 15.2 percent to 56 micrograms per cubic meter in the first half from a year earlier, Xinhua said, quoting municipal authorities.

But a check of previous reports found that first-half PM2.5 density in 2017 rose 3.1 percent, reducing the improvement over time.

Beijing’s average for the full year was 58 micrograms per cubic meter, more than double the level considered safe by the World Health Organization.

Despite the signs that seasonal production cuts have distorted the energy markets, the government appears to be doubling down on the policy.

Analysts are already seeing signs of overproduction to offset the effects of the output curbs expected next winter, in addition to making up for lost time from the last heating season.

“The tightness in coal has been exacerbated by some manufacturers boosting production before winter, when regulators tend to limit output to ease pollution,” Bloomberg News reported on July 19, citing Frank Yu, an analyst at the international energy consulting firm Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

The combination of higher production both before and after the winter shutdowns suggests that energy markets may have less opportunity to subside from spikes in demand.

Philip Andrews-Speed, a China energy expert at the National University of Singapore, said the reactions are a sign that industry has learned to cope with the government restrictions, while the country’s partially-liberalized energy markets have not.

“The problem with administrative measures like the closure of plants during the winter heating season is that, once used, manufacturers will assume that it will be repeated and will act accordingly,” Andrews-Speed said.

The government has coupled its restrictions with interventions to keep energy prices from rising.

In May, the NDRC told coal companies, utilities and traders that higher prices were “unsupported by market fundamentals,” according to Reuters. The statement was a not- so-subtle warning that price hikes would not be tolerated, regardless of demand.

In a series of moves, the agency pushed coal mines to increase supplies under long-term contracts and meet the government’s price target of 570 yuan (U.S. $83.50) per metric ton.

The NDRC reportedly urged utilities to stop buying coal and let inventories drop until prices came down. Leading utilities responded by halting purchases in the higher-priced spot market.

In an apparent claim of success for the policy, Xinhua reported on July 21 that the benchmark Bohai-Rim Steam Coal Price Index had dropped to 569 yuan ($83.36) per ton “due to government efforts to ensure sufficient supply and a slowing coal consumption.”

But a review of the index data at China Shipping Database website found that the weekly price readings had varied by only 1 yuan (U.S. 14 cents) since May 30, suggesting controls over market fluctuations.

Despite the machinations, thermal coal prices at China’s northern Qinhuangdao port reached 696 yuan (U.S. $101.96) per ton in June, Bloomberg said.

Effect on import prices

High demand was also reflected in import prices. Benchmark Australian coal prices climbed 40 percent since the start of the year, rising above U.S. $120 (819.2 yuan) per ton for the first time since 2012, CNBC reported on July 12.

China’s net coal imports in the first half of the year rose 12.6 percent to 144 million tons, the CNCA said.

In the short term, the government’s tactics to stall price hikes may have worked.

On July 31, Bloomberg reported that spot prices have cooled and coal futures had posted the biggest monthly drop in over year.

Analysts cited a combination of factors including the end of mine inspections, higher inventories at ports and heavy rainfall that raised hydropower output.

By July 23, spot prices at Qinhuangdao port had fallen to 646 yuan (U.S. $95) per ton, Bloomberg said.

But the government’s attempts to control prices have effectively blocked the supply and demand signals that would otherwise lead to lower consumption, forcing the authorities into more intervention schemes.

“If demand soars, so should prices to end users,” said Andrews-Speed.

“That should encourage individuals to turn down their air conditioners and companies to cut back output. But this is not happening,” he said.

It is unclear how long the NDRC can use restrictive measures to manage market forces before losses or shortages require additional steps. For the time being, China’s coal and steel producers are reaping higher profits.

In the first five months of the year, profits at coal companies with annual turnover over 20 million yuan (U.S. $2.9 million) rose 14.8 percent to 127.88 billion yuan (U.S. $18.7 billion), said CNCA director Wang Xianzheng, sxcoal.com reported on July 20.

In the first half, steel industry sales were up 15 percent to nearly 2 trillion yuan (U.S. $292.9 billion), while profits of 139 billion yuan (U.S. $20.3 billion) soared 151 percent, the China Iron and Steel Industry Association (CISA) said, according to Xinhua.