Can The Anti-Assad Coalition Produce The Goods In Syria? – OpEd

The US-led coalition in Syria hopes to reach its long-term goal by way of twin-track tactics.

The goal? To impose a crushing military defeat on Islamic State (IS), to liberate the territory it has occupied in Iraq and Syria, and to re-establish a sovereign state of Syria within its previous borders.

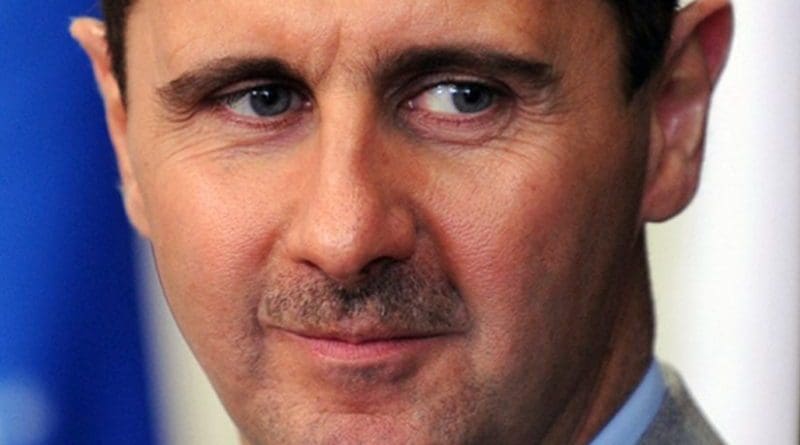

The twin-track tactics? To degrade Islamic State’s infrastructure and fighting capacity as far as possible, while at the same time to deploy every possible diplomatic and political means to bring the Syrian civil war to an end, thus releasing the forces currently engaged in fighting President Bashar Assad and each other, and turning them on IS.

A great deal depends on those boots on the ground in Syria. One lesson the West has learned is that fighting on Arab soil is usually a recipe for disaster, generating more opposition than it quells. So the coalition, exercising a self-denying ordinance, is restricting its mainstream activities to providing sophisticated air support for indigenous fighting units. Military experts appear to believe that at least 70,000 such troops would be needed to mount an effective co-ordinated campaign that could defeat IS in Syria – and that this number of non-extremist fighters actually exists within Syrian territory. At the moment, though, they are dispersed, lack a unified command structure, and many are engaged in fighting President Bashar al-Assad’s Syrian army in the long-lasting civil war.

That is why it is necessary to take a cold, hard look at the alternative – Assad, and his army.

Syria’s military is a hardened and disciplined fighting force of some 200,000 regular troops and a further 100,000 irregulars. Recently, under the cover of Russian air support, the regime has been making progress. It is currently taking back large parts of Homs and is only a few miles from Palmyra – the fabled pink-stoned city of monuments, where IS decapitated the 82-year-old curator, Khaled Al Assad, before beginning an orgy of cultural destruction.

To support the Assad regime and the Russians in their effort to recapture that amazing site is not to endorse the idea of keeping Assad in power indefinitely. But bringing an end to Syria’s civil conflict is an urgent priority – and is being treated as such by an impressive collection of 17 world powers plus the EU and the UN, now known as the International Syria Support Group (ISSG).

When they met in Vienna on November 14, the ISSG agreed that by January 1, 2016 political negotiations should take place between representatives of Assad’s government and the forces opposed to him, to be followed by an immediate UN-monitored cease-fire. The group allotted six months for Syria to form an interim unity government, and wanted free and fair elections to be held in Syria within 18 months.

To facilitate the cease-fire, the powers agreed that once negotiations were under way, they would stop all support and supplies to “various belligerents” on both sides of the Syrian civil war.

However in the room where the ISSG spent six hours in close consultation behind locked doors, an elephant, which all parties did their best to ignore, wandered about. Pinned to its forehead was the question: “What part is Bashar al-Assad to play in the battle against IS?”

In short, should Assad remain in power, if only on sufferance, and deploy his army, still loyal to him, against IS, or would his best contribution to the restoration of order to Syria be to leave the scene? The international community remains deeply divided over Assad’s fate. Believing the Syrian leader to be largely responsible for the conflict, the US, many European countries, Saudi Arabia and Turkey, call for his departure. US Secretary of State John Kerry has said the conflict will never end until Assad leaves.

Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, however, flatly disagrees. “We have reiterated that Syria’s future will be decided by the Syrian people alone,” he has said, including “the future of Assad.” Russia and Iran believe that as the legitimate head of government, Assad must be involved in the anti-IS effort and the future of the country.

The thought of collaborating with Russia’s gung-ho president, Vladimir Putin, in fighting IS probably sticks in the craw of many world leaders. Putin’s efforts to re-establish Russia as a global super-power have seen him seize and annex Crimea, while his proxy army has been trying to carve out a Russian-dominated enclave in eastern Ukraine. His incursion into the Middle East, and his massive military and air build-up in Syria, was clearly an effort both to enhance his influence on the international stage and, by supporting Assad, to sustain Russia’s long-standing military and commercial interests in Syria.

The US has charged Putin with concentrating his fire on Assad’s opponents rather than on IS. However true this may have been at the start of Putin’s air-strike campaign, the downing in mid-air of the Russian passenger jet on October 31, with the loss of all 224 people on board – a terrorist outrage claimed by IS – changed his priorities. Russia is now as committed as the rest of the world to defeating IS and liberating the 10 million people currently subjected to its brutalised and bloodthirsty rule.

France, currently leading the free world in its determined opposition to IS and all its works, seems under no illusion. “I was in Paris at the end of last week,” wrote MP Boris Johnson. London’s mayor, on December 7, “and the Russian leader’s face glowered sulkily from every billboard. “Poutin”, said the headline, “notre nouvel ami”. Many French people think the time has come to do a deal with their new friends the Russians – and I think that they are broadly right.”

It is all a question of priorities. What is the prime concrete objective? To remove IS and the threat it poses to the whole world. Everything else should be secondary. We need to end their hideous Islamist rule, with its beheadings, amputations and crucifixions. We need them out of Palmyra and put a stop to their philistine destruction of some of the world’s greatest antiquities.

The best hope for the future of Syria, and indeed of Iraq, lies in the recent agreement by ISSG to defeat and destroy IS, together with a plan for a new Syrian government. This really should embody the end of the Assad regime and his departure in one way or another, sooner or later. If it has to be done in such a way – perhaps through the ballot box – that neither Putin nor Assad lose face, so be it.