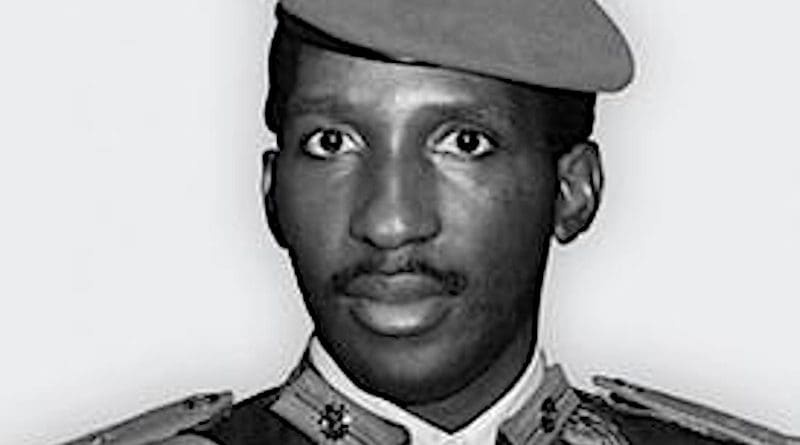

Thomas Sankara: An Icon Of Revolution – OpEd

By Yanis Iqbal

October 15, 2020, was Thomas Sankara’s 33rd death anniversary. On this day, he was murdered by imperialist forces at the tender age of 37. A Pan-Africanist, internationalist and Marxist, he was committed to the total liberation of the oppressed masses from the clutches of imperialism. Instead of bourgeoisie nationalism, Sankara believed in radical nationalism: a combination of anti-imperialist courage and unabashed humanism that pushes for revolution instead of neo-colonial settlement. Thus, he belonged to a pantheon of African revolutionaries like Amilcar Cabral, Samora Machel and Patrice Lumumba who understood the necessity of adopting socialism for the fundamental transformation of their respective societies. Looking at the short life of Sankara, one can’t help but be moved by the way in which he emerged through the anguish and aspirations of millions of Burkinabe civilians and commanded a radical project of socialist transformation.

Man of the Masses

On 25 November, 1980, a group of military officers led by Colonel Saye Zerbo staged a coup against Aboubakar Sangoulé Lamizana’s largely dysfunctional government, citing, among other reasons for their action, an “erosion of state authority.” Establishing the Military Committee for the Enhancement of National Progress (CMRPN), Zerbo detained the former president and many other officials, scrapped the constitution, dissolved the National Assembly, outlawed parties, and prohibited all political activities. After taking power, Zerbo harshly implemented a comprehensive austerity package which reduced budgetary expenditure and weakened the fiscal capacity of the public sector. In addition to austerity, Zerbo’s CMRPN repressed the labor movement, formally suspended the right to strike and arrested radical students.

As the concoction of austerity and authoritarianism was being prepared, corruption was simultaneously increasing. Reports revealed massive embezzlement at a publicly owned investment bank by its former head; exposed a Ministry of Finance service director for taking payments from several merchants in exchange for forged documents authorizing wheat imports; and raised questions about real estate speculation done by private merchants, state officials and army officers which was increasing housing rents for citizens. These corruption cases received a remarkable amount of coverage during Sankara’s tenure as the secretary of information from November 1981 through April 1982. As the secretary of information, he put a halt to the intimidatory tactics of the state and encouraged reporters to provide citizens with the “most accurate information possible”.

On 12 April, 1982, Sankara sent a formal letter of resignation to the president. In it, he criticized the CMRPN for its “class” character and for serving the “interests of a minority”. He further announced his resignation publicly over a live radio and proclaimed: “Woe to those who would gag their people.” In response, the CMRPN stripped Sankara of his rank as the captain, arrested him and deported him to a military camp in the Western town of Dedougou. By this time, the military was factionalized and one of the factions decided to overthrow Zerbo through a coup. Sankara was against a strictly military takeover and wanted a political program to be elaborated so that fundamental social changes could be produced. Though Sankara’s supporters refrained from undertaking any military action, other military officers moved ahead with a coup. On 7 November, 1982, a military action, led principally by Commander Gabriel Somé Yorian – a politically conservative officer who had served as a minister in every government since 1971 – occupied key locations in Ouagadougou, overthrew the CMRPN and formed a military-led government called the Council of Popular Salvation (CSP).

The CSP was unstable and faction-ridden from the start. While the conservative bloc wanted to operate within the pre-existing framework of imperialist subjection and make minor changes, the revolutionary junior officials – who were drawn into coalitions that included leaders of organized left-wing parties, academics, student activists, trade unionists, and other civilians – were oriented towards the construction of an anti-imperialist front. Sankara – who was restored to his previous rank of captain – used the administration as a public platform to propagate revolutionary ideals and agitate for more changes. When he was sent to talk to a congress of the secondary and university teachers’ union, Sankara said that the army was facing “the same contradictions as the Voltaic people” as a whole and affirmed that “struggles for liberty” were gaining support within the military.

On 10 January, 1983, Sankara was named prime minister by an assembly of the CSP. While taking the oath on 1 February, he emphasized that government members were there to serve the people, “not to serve themselves.” The people wanted freedom, he said, but “this freedom should not be confused with the freedom of a few to exploit the rest through illicit profits, speculation, embezzlement, or theft.” As prime minister, Sankara embarked on an extended international trip, which culminated in his attendance at the summit of the Non-Aligned Countries in New Delhi, India. His trip included visits to Libya and North Korea, considered as pariahs by the Western governments. From 7 to 13 March 1983, Sankara was at the summit of the Non-Aligned Countries in New Delhi, India, where he met various Third World revolutionary leaders, including Fidel Castro of Cuba, Samora Machel of Mozambique, and Maurice Bishop of Grenada.

In his speech to the summit, Sankara criticized US foreign policy. “The Israeli government, publically supported by the United States, despite the unanimous condemnation of the entire world, invaded Lebanon with its army, submitted the capital Beirut to ruthless destruction”, he said. “Despite the ceasefire called for by the international community, the Israeli government has allowed the indescribable massacres of Sabra and Shatila, and whose leaders [in Israel] should be prosecuted for crimes against humanity.” On top of US policies in the Middle East, Sankara condemned American imperialism in Nicaragua and El Salvador and expressed solidarity with the people of South Africa, Mozambique and Angola.

On his return from New Delhi, political divisions within the CSP deepened. On March 26, 1983, Sankara gave a fiery speech at a mass rally organized by the government where he clearly outlined his revolutionary plans. In his speech, Sankara criticized bureaucrats, businessmen, politicians and traditional and religious leaders. Using a participatory call-and-response method, he said:

“Are you in favor of us keeping corrupt civil servants in our administration?

[Shouts of “No!”]

So we must get rid of them. We will get rid of them.

Are you in favor of us keeping corrupt soldiers in our army?

[Shouts of “No!”]

So we must get rid of them. We will get rid of them.

Perhaps this will cost us our life, but we are here to take risks. We are here to dare. And you are here to continue the struggle at all costs.”

While Sankara’s speech elicited an enthusiastic response from the people, the speech of President Jean-Baptiste Ouédraogo – who belonged to the conservative faction – was lackluster and failed to electrify the crowd. As is evident from this, the gulf between the revolutionary and conservative factions was widening.

On 17 May, 1983, military units detained Sankara and Commander Lingani and took up strategic positions around the capital. These were the intimations of a new coup against Sankara’s radical faction. President Ouédraogo announced that the CSP had decided to “remove from its ranks all those who were working to turn it from its initial path through behavior, declarations, and acts that were as demagogic as they were irresponsible.” He was implicitly accusing Sankara and Lingani of breaking the stranglehold of the conservative faction and advancing an alternative, revolutionary policy paradigm.

In order to reconstitute a conservative administration, President Ouédraogo named Colonel Somé Yorian, one of the primary authors of the coup, as the secretary general of national defense and purged the cabinet of all those individuals who were politically associated with Sankara. The new administration came to be widely known as the CSP-II. This counter-offensive against Sankara had the involvement of the French imperialists. On 16 May – just a day before the coup – Guy Penne, the adviser on African affairs to French President François Mitterrand, had arrived in Ouagadougou and left the next afternoon, while the coup was under way, and after agreeing to provide the new government with more financial aid.

The decision to oust Sankara did not go as planned. Over 20‒21 May, popular demonstrations were organized throughout Ouagadougou, involving students, radicalized poor people and trade unionists. Protest cries of “Free Sankara!” roared all over the streets and anti-imperialist slogans, particularly against France, reverberated throughout the city. Clandestine committees of civilians were formed and revolutionary supporters of Sankara underwent military training in the garrison in Pô where the troops of Sankara’s old commando training base had refused to recognize the authorities in Ouagadougou. It was here that Captain Blaise Compaoré, a captain and co-revolutionary, had fled in order to evade arrest.

On 4 August, 1983, 250 commandos from Pô left the garrison for the capital with aim of overthrowing the CSP-II. With the help of the clandestine civilian groups, the city’s power was cut and at 9:30 pm, the commandos captured all their targets. In the meantime, junior officers took over the air base and the artillery camp. By 10 pm, Sankara proclaimed the overthrow of the government on the radio. In his address to the nation on the evening of 4 August, Sankara announced the formation of the National Council of the Revolution (CNR) and urged supporters to immediately form Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs) “everywhere, in order to fully participate in the CNR’s great patriotic struggle and to prevent our enemies here and abroad from doing our people harm.” The new government’s main goal, he said, was to work in conjunction with the people and help them achieve their “profound aspirations for liberty, true independence, and economic and social progress.”

Building a Socialist Economy

The CNR was resolutely opposed to the various forms of subjugation existing in the country and its critique of the established system was sweeping. The general outlook of the CNR administration was defined by Sankara in his important Political Orientation speech – given on 2 October, 1983 – where he used Marxist and dependency theory to construct the theoretical foundations of the August revolution. In the speech, he stated: “The fear that the struggle of the popular masses would lead to truly revolutionary solutions had been the basis for the choice made by imperialism: From that point on, it would maintain stranglehold over our country and perpetuate the exploitation of our people through the use of Voltaic intermediaries”. Terming this as “neo-colonialism”, Sankara said that the “primary goal of the revolution is to transfer power from the hands of the Voltaic bourgeoisie allied with imperialism to the hands of the alliance of popular classes that constitute the people.” Sakara’s incisive condemnation of imperialism was accompanied by the use of moral lexicon which interwove a militant revolutionary attitude with the soft glow of emotions. Integrity, for example, was highly emphasized by the CNR and on the first anniversary of the 4 August revolution the council renamed the country “Burkina Faso”: land of the upright people.

Sankara’s government promoted the construction of an independent, self-sufficient, and planned national economy. Sankara’s model of self-reliance meant that the national economy would operate based on domestic interests. The needs of peasants and rural communities would take precedence over exports that served international interests. The government would depart from a tone-deaf approach in allocating resources and focus instead on the needs of people and institutions at the local level. In order to achieve this goal, the government relied on social mobilization and community self-help projects to promote development. These new initiatives produced noticeable changes in the public health sector. By 1986, the government built 7,460 primary health posts (almost one per village) throughout the country; public health spending increased by 27% between 1983 and 1987; and 2.5 million children received vaccinations. Under Sankara, Burkina Faso also became the first country to acknowledge the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

A self-reliant economic framework – which prioritized social development over profit maximization – translated into staunch anti-neoliberalism. Sankara refused to accept the Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs) that the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) were imposing on third world nations throughout the 1980s. He abhorred the idea of passively receiving loans from imperialist institutions. In a speech given in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, at the twenty-fifth conference of member states of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), he had powerfully declared: “The debt is another form of neo-colonialism, one in which the colonialists have transformed themselves into technical assistants. Actually, it would be more accurate to say technical assassins… The debt in its present form is a cleverly organised re-conquest of Africa under which our growth and development are regulated by stages and norms totally alien to us.”

In order to avoid a large budget deficit, Sankara proposed a model of modest living. To this end, the CNR transformed the civil service and erased any sign of ostentatious living. The revolutionary government froze civil service salaries; reduced housing allowances by 25‒50%; and made it obligatory for public employees to contribute to a variety of special funds and levies to aid drought victims or finance development projects. Two-thirds of the government’s auto fleet was sold off, and only small cars were kept. Sankara himself used a small, low-priced Peugeot 205.

Imperialist Assassination

On 15 October, 1987, Sankara was attending a meeting with his small team of advisors at the Conseil de l’Entente headquarters. 15 minutes into the meeting, shooting erupted in the small courtyard outside, in which the president’s driver and two bodyguards were killed. Upon hearing the gunfire, everyone inside took cover. Sankara got up and told his aides, “It’s me they want.” He left the room to face the assailants. He was shot numerous times, and died on the spot. The gunmen then entered the meeting room and killed everyone but Alouna Traoré, who survived and fled the country.

Sankara’s assassination was a result of a complex convergence of interests. Firstly, Blaise Compaoré had personal interests in overthrowing Sankara and concentrating power in his own hands. Compaoré had married to Chantale Terrasson de Fougères, the adopted daughter of Côte d’Ivoire’s President Houphouët- Boigny. While Compaoré and Fougères wanted to live an ostentatious life, Sankara’s radical project of modest living – aimed at helping the poor and establishing a socialistic culture of humanism – constantly acted as a hurdle in their pursuit of personal ambitions.

Secondly, geo-political actors like France and USA were interested in killing Sankara and re-incorporating Burkina Faso into the structural arrangement of imperialist subordination and global capitalism. The imperialist interests of major powers neatly coincided with the personal interests of Compaoré. Thus, Compaoré functioned as an imperial-backed domestic actor who could simultaneously enrich himself and advance the objectives of neoliberalism by murdering Sankara.

For France and USA, Sankara’s revolutionary policies constituted a tangible threat to imperialism. When French president Francois Mitterrand had arrived in Ouagadougou in November 1986, he had directly experienced the threat posed by Sankara’s revolutionary politics to the project of unfettered neo-colonialism. During Mitterrand’s visit, Sankara disrupted the normal diplomatic discourse and presented the French president with a forceful anti-imperialist dialogue. He talked about colonial policies in Palestine; defended Nicaragua against USA’ hybrid warfare; and criticized Paris for its policies in the African continent and towards African immigrants in France. At the end, Mitterrand said, “I admire his great qualities, but he is too forthright; in my opinion he goes too far.” He also added, “This is a somewhat troublesome man, President Sankara”. A year after these remarks, Sankara was assassinated. Many believe that Jacques Foccart, a key French intelligence figure with extensive networks throughout Africa, had actively engaged in the assassination plans.

USA, too, had concerns about Sankara’s revolutionary project. Sankara had converted Upper Volta – a formal colony till 1919 and a neo-colony till 1960 – into Burkina Faso – the land of revolutionaries who challenged imperialism. This was bound to be troublesome for the US which was building an informal empire and wanted a friction-free Global South, subservient to America. Herman Jay Cohen – former Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs – had written that, as a member of the American Executive, “I accused Sankara of trying to destabilize the entire region of West Africa…I insisted that Sankara was hurting the image of the entire French community in West Arica”. From this, it is evident that the US was interested in containing Sankara’s revolutionary project and coordinating its hegemony with France’s sub-imperial dominance in Africa. To do this, USA used the services of Liberian mercenaries who helped assassinate Sankara. Charles Taylor, for instance, was a Liberian who was released from an American jail with the help of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and then asked to infiltrate African revolutionary movements. It was later found that Taylor had been involved in the assassination of Sankara. It is important to remember that the Liberian mercenaries were not solely financed by the US. There was another agreement that Compaoré and Muammar al-Qaddafi of Libya would help Charles Taylor and his men seize power in Liberia in return for the assassination of Sankara. Qaddafi chose to fund the murder of Sankara since the relations between the two had become strained over the latter’s efforts to mediate among different warring factions in Chad (a war in which Libya had intervened).

A week before his assassination, Sankara gave a speech in Ouagadougou at the inauguration of an exhibition honoring the life of Cuban revolutionary Ernesto Che Guevara, who had been killed exactly twenty years earlier. In the speech, Sankara proclaimed: “we want to tell the whole world today that for us Che Guevara is not dead… you cannot kill ideas. Ideas do not die. That’s why Che Guevara, an embodiment of revolutionary ideas and self-sacrifice, is not dead.” These words aptly describe Sankara’s assassination. Though Sankara was murdered by imperialist bullets, his revolutionary conviction in class struggle and humanism continues to inspire a countless many to oppose oppression and exploitation.