Now It’s ‘All Up To Joe,’ Or How The State Is Destroying The Market – OpEd

The results of the congressional elections will have long-term and short-term implications, but their significance for the economy and markets clearly should not be overestimated. Both perspectives have one commonality that represents a constant of at least the last two decades: government is intensely left-leaning. Any respite from the toxicity of government expansion and regulatory pressure, in the form of, for example, a heterogeneous Congress, is thought to be perceived by economic agents as a boon. However, the realization that the leftward vector will continue shapes economic agents’ expectations and adaptive behavior, which are clearly not based on confidence in economic freedom and free competition: now “everything depends on Joe” (a phrase from the movie Meet Joe Black), i.e. on government, whatever it may be. This is why there is reason to believe that the nominal postulate of the importance of the political arrangement for economic agents has ceased to have actual significance.

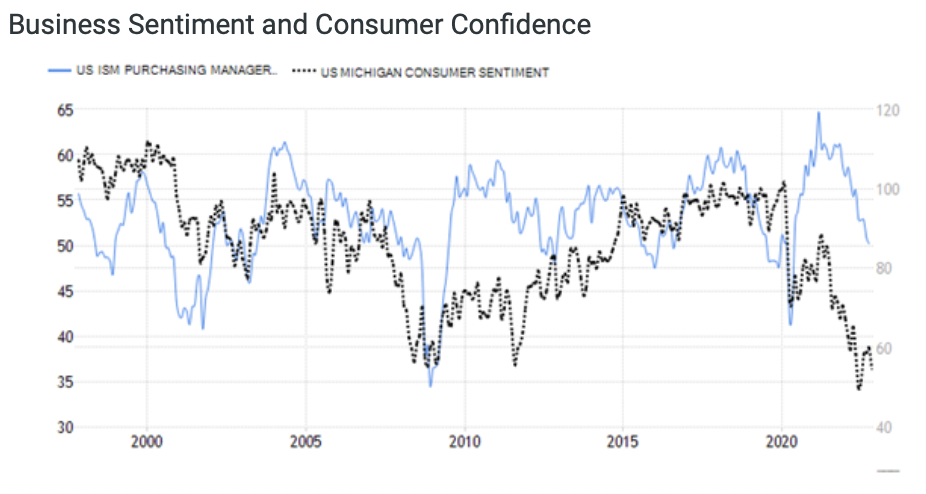

It is not the government loosening its grip that the markets have been rejoicing in recent days. Markets (investors and algorithms) and Main Street (producers) are now reacting to every facial expression on the face of the FED and trying to survive without much of a plan for tomorrow. Just look at the withering venture capital market, the M&A market, the SPAC industry and the general decline in capex. The slowdown in consumer inflation and, consequently, the coveted prospect of a slowdown in rate hikes caused a veritable euphoria among manual investors and provided a corresponding trigger for algorithms: markets bounced back up, fueled by closing stop-loss short positions.

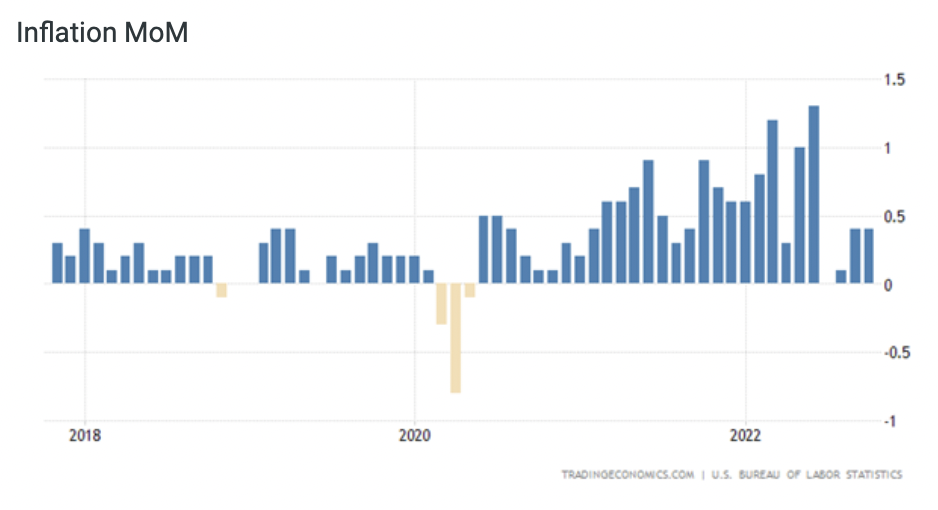

But this reaction should not be taken as a wake-up call to the economic outlook: the outlook is still worrisome. Inflation is still high, with October’s CPI reading of 7.7%, down for the year, due to the high base calculation, October 2021 inflation, which is up sharply from September 2021 by 0.9%. Meanwhile, the monthly inflation rate has not declined and remains at 0.4%. The 2021 annual rate base is further reduced, and if the monthly rate of increase remains the same, the annual rate will increase.

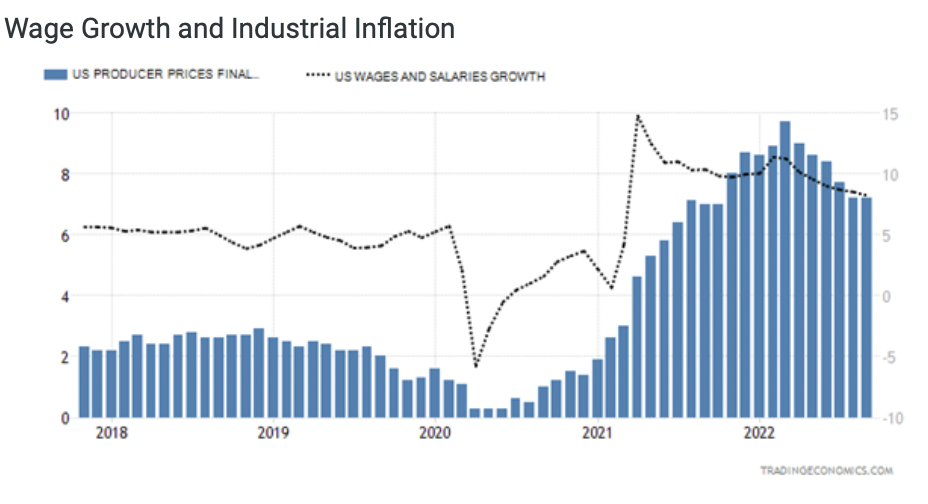

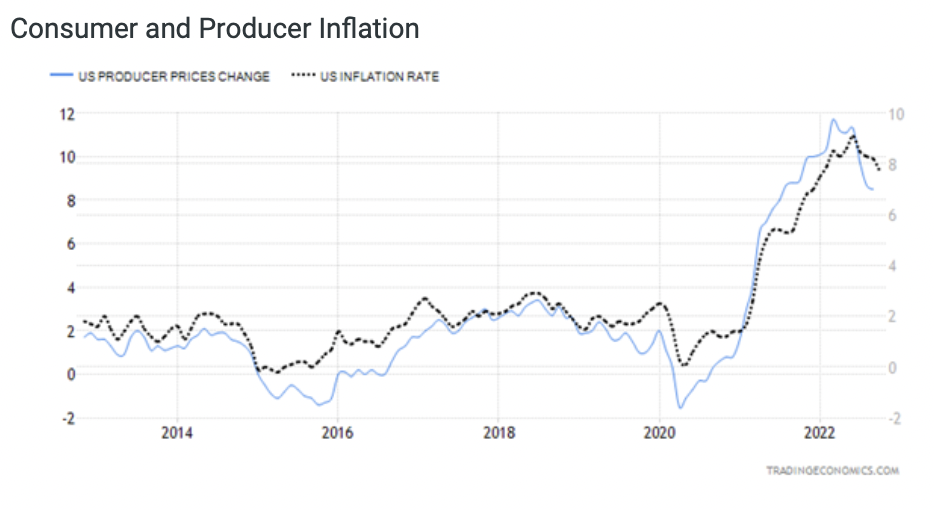

The main components of inflation remain at high levels: a strong labor market – high job openings, labor shortages and high wages, and high producer price inflation – continue to keep CPI at high levels.

The transit of inflationary pressures from producers to consumers is not over yet: regulatory and fiscal overhangs, coupled with geopolitical risks in commodity markets, are constantly weighing on producers.

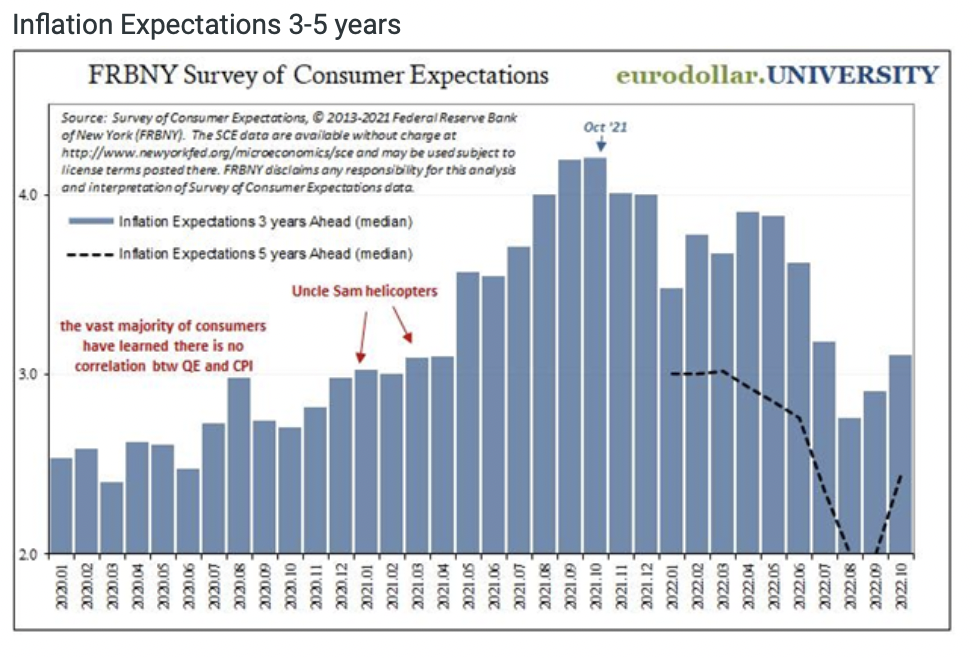

Inflation Expectations at different horizons are rising again.

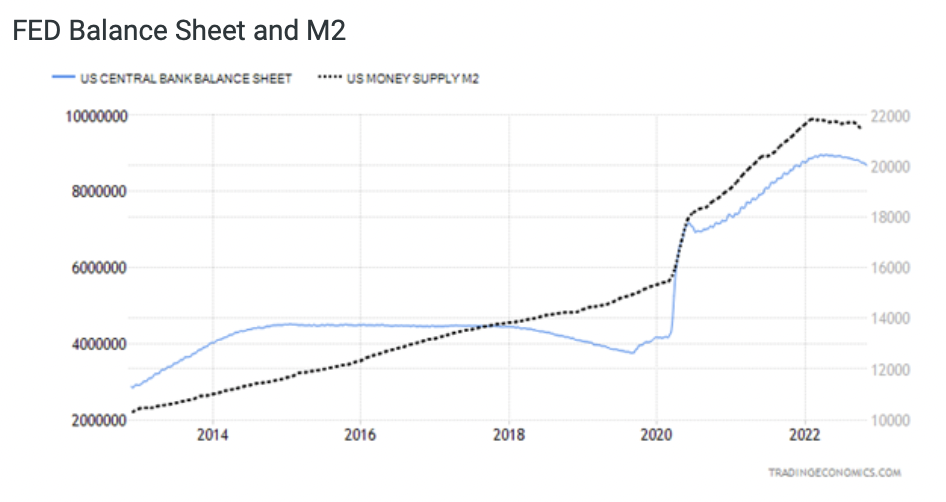

Absorption of hypertrophied liquidity through balance sheet reduction is at a relatively low rate compared to the rate of balance sheet growth in covid times, and the government’s desire to maintain social stability by maintaining high employment and large-scale government programs largely offset the efforts of the FED. The public is presented as saying that the economy is stable, risks of severe recession are not obvious, a soft landing is highly probable.

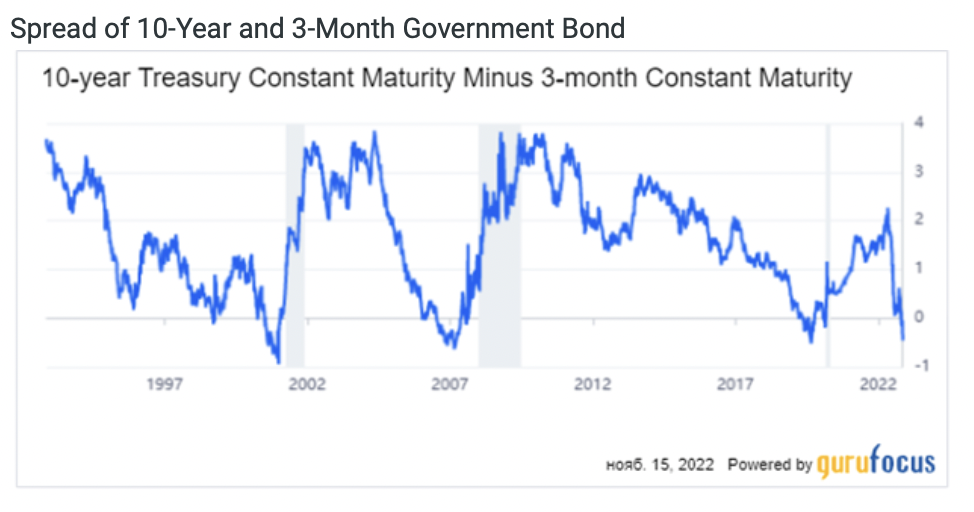

Smart debt markets have long ago and clearly recognized the prospects of hopeless illusions: the flattening of the curve into an inversion of spreads and the ever-rising dollar have made clear how investors view the near future.

The rising cost of borrowing is making short-term debt garbage, and the doom loop the government and the Fed find themselves in, having to simultaneously deal with prohibitive inflation and the threat of a severe recession, is killing any positive outlook for tomorrow.

In such a situation, it makes more sense to shift risk and exposure to fixed income into the future, where the government will be forced to play their own tuned fiddle and lower rates again to revive the economy and pull it out of recession with another dose of cheap liquidity instead of real market bailouts, dumping ballast of inefficient businesses and winding down government expansion in the economy.

Equity investors understand this too, as they make their decisions and tweak their algorithms: the main driver of asset pricing is the Fed’s rate and balance sheet decisions, and both tactical and strategic decisions are made accordingly.

The balance sheet is important because it will be clear to what extent the Fed and the government will tolerate asset depreciation for the main wallets – pension funds, ETFs, and insurance companies – as the increased margin positions in long debt accumulated during zero rates and about the same yield could turn into a snowball rolling down the mountain – we recently saw such a situation in the UK.

The rate is important for the obvious reason that it actually determines the availability of money, i.e., the cost of borrowing and thus the value of assets.

Government expansion in various forms – from the employing state to social programs, tax tightening, expansion of the regulatory overhang, and other toxic decisions of “socially oriented” government – is no longer essential to markets. In fact, a self-regulating competitive market environment has been sterilized: the economy and its agents are directly dependent on the state. Accordingly, the main competitive effort is directed toward access to resources provided in one way or another by the state by expanding the fiscal burden and centralizing redistribution. The state is no longer engaged in stimulation, it actually models and dictates the economic behavior of agents.

We are reaping the results of this growth of direct participation in economic processes by the state as an active actor today. And the disappointing assumption is that the free market is actually over: the “squeeze-out” effect of government expansion has resulted in a change in the competitive focus of market players on the state.

Multifactor models are simply losing their effectiveness and real meaning in asset valuation and investment decision-making. And this no longer applies only to macro-investment, but is also true at the level of corporate valuations. All that matters now is monetary and FED balance sheet adjustment decisions, business details become less important in analysis for asset selection and allocation: macro factors replace micro factors in asset valuation and investment decision-making.

Two important conclusions can be drawn from this picture.

The first is that investment decisions need to be based on updated principles, which are becoming simpler and more linear in a sense. Alpha is no longer hidden in technological innovativeness, market competitive efficiency, exceptional management or the ability to evaluate and select a quality asset with high growth potential. The added value is now in the maximum adaptation to the macroeconomic policy of the state, and this concerns both businesses and investors.

The second: this state of the economy is highly unstable, and the prospects are not very positive, because the bases of economic exchange remain market-based, which means that the state can never account for all risks, prospects and probabilities, unlike the scattered knowledge of heterogeneous agents with different interests, skills, resources and goal-setting in a market economy.

This suggests that everything can break down in one click. Or in two. After all, we know that the centralization of redistribution is the path to bigger problems, and that is where we are headed in broad strides for the third decade.