Tokayev Should Wonder Why Modern Countrymen Of The Author Of Kazakhstan’s Hymn Say ‘[We] Alshyns Are Not Kazakhs’ – OpEd

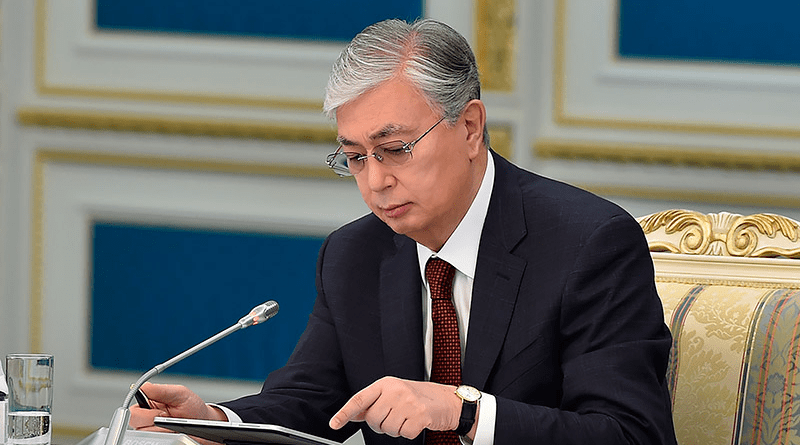

On March 15, the third Kurultai (National Congress) took place in Atyrau under the chairmanship of the President of Kazakhstan. The Kazakh leader addressed the opening of the event. The speech lasted for quite a long. But honestly, there was nothing new in it. Yet the words, reflecting the status of the event, were spoken, listened to with attention, and welcomed with loud applauses. “First of all, it is imperative to strengthen the unity of our people” and “the unity of the people begins with the unity of its intelligentsia”, he said.

Let’s step back in time for a little bit to the very beginning of the modern national Kazakh state’s existence and find out how the reintroduction of the concept of Kurultai back into Kazakhstan’s first cultural life, and then into its political life, too, had been progressing. Already in the first year of existence of the Republic of Kazakhstan, in 1992, it was decided to hold the World Congress of Kazakhs in Almaty involving representatives of the Kazakh diaspora from 30 foreign countries and term it the 1st World Kurultai of Kazakhs. It was a purely ethnocultural event, and it had nothing to do with the political State-building process in Kazakhstan. The 2nd World Kurultai of Kazakhs took place 10 years later, in 2002, the 3d one in 2005, 4th and 5th ones in 2011 and 2017, respectively. Again, they all had no connection to the political processes in Kazakhstan.

In 2022, the current Kazakh President, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, signed a Decree on the creation of the national Kurultai. Since, in the present case, it was about a political institution, this decision was regarded by many in Kazakhstan as a kind of step towards returning the ethnic Kazakh society, which, according to Seytkasym Auelbek, a Kazakh sociologist, in its fundamental characteristics, remains patriarchal and tribal, to its roots in the political sense of that word. Some of the Kazakhstani political experts were quite puzzled by Tokayev’s decision to revive the Kurultai as a tool and a structure of his nation’s internal politics. For, in normal Kazakh understanding, Kurultai was and still is seen as tribal representatives’ assemblies convened to determine the decisions on the nation’s most important domestic and foreign policy issues and assign individuals to leadership positions and titles. We repeat that the ethnic Kazakh society, according to Seytkasym Auelbek, a Kazakh sociologist, in its fundamental characteristics, remains patriarchal and tribal. Therefore, it can be assumed that the Kazakh leadership, who already said “a”, would probably have to say “b”, too, as the Russian proverb has it. Namely to revive the Kurultai notion as it was originally intended. This was the way the first Kazakh President, Nursultan Nazarbayev, wasn’t willing or prepared to go. Even less ready for it is the current Russophile Kazakh leader, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. In the current circumstances, it’s a very slippery path. But the current ruling regime has already begun its journey down that path. Although the Kurultai is a very serious political event in the traditional Kazakh understanding of its purpose, the ruling regime in Astana certainly wants to see it as just a presidential consultation body.

But by the force of circumstances, what it created under that name for its purposes, may eventually be transformed into something more relevant to its title. Because there is a demand for it against the background of the growing differences among the representatives of the different groups of Kazakhs, on the one hand, and between some of them and official Astana, on the other. Firstly, the proof of this are headlines in the media like “The Senior zhuz has nothing to do with Kazakh statehood” and “Alshyns [natives of the western part of Kazakhstan] are not Kazakhs”. And secondly, what Wikipedia describes as follows: “People in the western provinces are dissatisfied with the discrepancy between the strategic role of the region, which ensures the economic stability of the country, and its place in the socio-political priorities of Kazakhstan’s domestic policy. In addition, as in the rest of the countries of Central Asia, the struggle for territorial autonomy is caused by the fact that in Kazakhstan there is a clan approach to the formation of power structures, which results in the dominance of representatives of certain provinces, which is not liked by people of other parts of the country”. The ruling regime still prefers to ignore all of it.

Official Astana likely has neither the ability nor the desire to deal with the challenges of that kind. It can be assumed that the Kurultai the way it was originally meant to be used would have been a good platform for discussing those issues and finding solutions to them. But the existing Nazarbayev’s pyramid of power inherited by Tokayev, might be too rigid to act flexibly and afford the luxury of letting someone other than itself deal with such matters. So here is a kind of one-way street without room to maneuver if some change of course is needed. That pyramid of power was the brainchild of Nazarbayev, and it seems he knew quite well how to manage it and what to avoid in doing so. Tokayev evidently lacks much of this, as well as historical knowledge and understanding of the Kazakh traditional mentality. It may be assumed that he creates some of these problems on their own or with the filing of his advisers. Tokayev therefore probably now faces more problems when managing this pyramid, than Nazarbayev did at his time. This can probably be said about his proposal to establish the national Kurultai instead of the National Council of Public Trust (NCPT), which used to exist, and convene its meetings. As they say in Russia: “What you name your boat, so it will float”.

In pursuing domestic policies, the first president of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev, who had been brought up on the Kazakh ethnic tradition, and the Kazakh folk stories, known as the Epics on 40 Heroes of the Crimea, always was not averse to using the historical concepts and terms, familiar to people living in the traditional Kazakh environment. Yet never once, during his 30 years in power, he was seen even talking about the possibility of convening the Kurultai. Since the latter, as a great convention of nomadic steppe hordes, must be convened only on the very great causes for them all. Let’s attempt to provide an explanation for this idea in a simplified means. The traditional Kazakhs would have described the Second Continental Congress that had voted to adopt the Declaration of Independence on July 2, 1776, which led to the group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America becoming the United States of America, as a kind of the Kurultai gathering. The same can be said concerning the extended meeting of the Security Council of the Russian Federation that took place at the Kremlin on February 21, 2022, and officially marked the start of the war with Ukraine that has continued for over two years now. There’s nothing really in common between those two events, other than the fact that they marked pivotal moments in the histories of America and Russia, respectively. This author is making such a comparison just to provide those far away from the Kazakhstani context with a general understanding of the Kurultai idea in Kazakh traditional perception.

The thing here is that after formally putting forward such an idea and establishing a relevant institution, the ruling regime is likely to face, under the action of the inevitable law of necessity, an increasing number of requests from the public to implement it the way it should be. The first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, most likely was not ready to go along with such requests regardless of whether or not they had been.

At one meeting in the 1990s with the high-profile public, political, and cultural figures of Kazakhstan, he was advised to establish the Council of biis (biis, prominent representatives of the Kazakh uluses or hordes, and tribes who acted as kind of a link between the institute of the State and the tribal groups in the traditional Kazakh society; in ancient times, each Kazakh clan had its bii at the head of the clan). To which he responded, “There is no such thing as self-styled biis. As such, they should represent their tribes and clans. The restoration of the institution of biis means restoring the tribal-clan system. You want that, don’t you?”. Of course, no one present dared to answer this question in the affirmative. Thus, the idea was abandoned.

The moral of this story is that the one who heads Kazakhstan the way it is today has to have a good understanding of Kazakh traditions of relations between the uluses (zhuzes), tribes, and clans to prevent the use of the concepts related to them for current political purposes. For in this case, inevitably there soon will be a question of going back to the rules, upon which were originally built the Kazakh unity and statehood; the rules, which presuppose equal representation from the three historical regions (hordes, zhuzes) of Kazakhstan in the national decision-making system. But Nursultan Nazarbayev, the first President of Kazakhstan, took a different path from the beginning.

And this is not just this author’s conclusion. As Sally Nikoline Cummings concluded in her study “The Political Elite in Kazakhstan Since Independence (1991-1998): Origins, Structure and Policies”, the Kazakh pyramid of power had the following form in the late twentieth century: “Approximately 40% of members of the 1995 political elite appeared to be from the Senior Horde [zhuz], 28% from the Middle and 9% from the Junior”. Such a balance of power within the Kazakh elite is generally maintained even now, after almost three decades. Moreover, the proportion of the Junior zhuz representatives among the members of the Kazakh political elite has now dropped to 3%, or even 2%. And they all occupy positions of minor significance in the formal structures of the Kazakh political environment. That is, the Junior zhuz was and remains in a losing position even though its homeland, Western Kazakhstan, is a region-donor for other regions of Kazakhstan.

Last week Kassym-Jomart Tokayev paid a visit to the Atyrau province in Western Kazakhstan to take part in the third Kurultai (National Congress) held in the provincial center. In 1956, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev proposed transferring the entire oil production zone in Kazakhstan to Turkmenistan, Zhumeken Nazhimedenov, then a 21-year-old youth, wrote a poem called “My Kazakhstan”. Shamshi Kaldyayakov, another representative of the Junior zhuz and a composer, wrote the music to it. This song immediately became an anthem for Kazakhstan’s unity, and 50 years later, in 2006, it was officially adopted as the Kazakh national anthem. And now, the trend that says “Don’t be a Kazakh, be an Alshyn” is spreading on social media among the natives of Western Kazakhstan. An alarming tendency, is it not? President Tokayev should wonder why modern countrymen of the author of Kazakhstan’s hymn say “[We] Alshyns Are Not Kazakhs”. But, to be honest, here, the answer is very simple and lies on the surface. It can be found in the foregoing citation from Wikipedia.