The Process Of Securing A Contract In Syria, 1994 – OpEd

I visited the capital city of Syria, Damascus, for the fifth time in 1994, alongside Jeff Green, the British General Manager of the American-Turkish joint venture company I was working for. There was a need for a new water-tube steam boiler by the Syrian public oil refineries.

The United States had imposed an embargo on Syria at the time. However, Canada had not, so our company’s Canadian division could have submitted a bid. We prepared the bid on their behalf in Ankara, Turkey. We attended site visits and customer meetings posing as employees of the Canadian company.

One of us (Jeff) was British, and the other (myself, the author) was a Turkish citizen. It didn’t matter, as the bid was submitted on behalf of the Canadian company. Once we secured the contract, everything – the design and manufacturing – would be carried out by us in Ankara. Canada would receive $50k for acting as an intermediary.

Our Syrian Armenian representative, George Seropian, whose ancestors had fled from Maras province in 1915, would be paid $25k. The final bid price was $1.7m. The water-tube boiler had a steam capacity of 55 tons per hour, producing 20-bar superheated steam. We had completed a similar project before, so the design was ready. For us, it was an easy bid. We had submitted our bid on our previous visit and faced competition from German, French, and Chinese firms. The Chinese company was disqualified due to inadequate quality. We offered the shortest delivery time at the lowest cost.

One of the members of the evaluation committee brought up an item in the tender specifications. They requested the operation and maintenance manuals. These manuals are typically prepared specially for the end-user customer personnel at the time of final delivery of the product, not at the contract stage. All we could do was promise to provide them. However, we found ourselves in a bind on how to provide these manuals, which we were told to deliver by the next business day.

We returned to the office of our representative in Damascus. It was after business hours, and the secretary had gone home. Due to the seven-hour time difference, our Canadian office was still in operation. There was no possibility of making a phone call. The Syrian Intelligence Service was listening in and connecting calls late. The internet did not exist at the time.

We sent a short fax to our Canadian office requesting them to fax us the essential pages of the operation and maintenance manual for a similar project. The incoming fax would first go to the Syrian Intelligence Service, and if they approved it, it would be forwarded to us. The fax machine started up at midnight, and pages of the operation and maintenance manual began to arrive from our Canadian headquarters. We received 20 pages of hard-to-read text. Jeff and I took turns at the computer, retyping the faxed text. We added new information specific to Syria, revisited the boiler description, and copy-pasted the non-existent parts from other texts. We corrected spelling and expression errors, and by dawn, we had completed about 100 pages of the new operation and maintenance manual. We added images, printed them out, made photocopies, and bound them into a book using spiral binding.

By morning, ten sets of operation and maintenance manuals were ready. We handed them over to our representative, who went to the public company office with great joy and submitted them. The next day, we signed the contract.

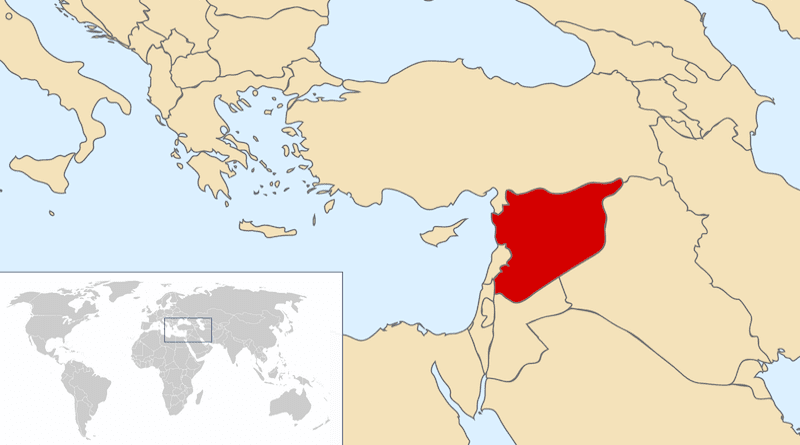

We sold the product at a higher price than the domestic market. We manufactured it in less than a year and shipped it from Mersin to the Latakia port. We charged extra for the installation at the refinery. We made a good profit. The refinery was in the northeastern corner of Syria. Now, that area is in ruins. It’s no longer under the control of government forces. Who knows who controls it now? Educated Syrians are no longer there. They have fled the country. That lucrative market is gone for us. It will take decades to re-establish.

In the world of business, we sell goods and services when there is peace in the region. We provide employment and investment, and we earn money.

In times of war, only arms dealers make money. War traders, arms manufacturers don’t live in these regions themselves. War only benefits them. The best companies with the latest technology make money. The people of our region involved in the war fight each other and only suffer. There is no winning side. War drains all resources from all sides. If you want to avoid war, you must always be ready for war with deterrent power. We have to put Altay’s new-generation battle tanks into mass production. We have to build better ones than F16 fighter jets. We must produce better unmanned aerial vehicles and missiles than Patriot and S-400 surface-to-air missiles. We must educate and train military command staff in the best way possible to manage human resources well in times of a war environment. In this difficult geography, we have no choice but to do all this and more to survive.

During the Syrian order process, we learned that one must be flexible and adaptable in international business. Despite the late-night scramble to create operation and maintenance manuals, we made it work. We had to tap into our resources, think on our feet, and utilize what we had. In the end, we successfully secured the contract.

We also realized the significance of local partnerships in navigating the intricacies of foreign markets. George Seropian, our representative, was crucial in assisting us to understand the Syrian business environment, especially regarding the embargo. We recognized the importance of cross-cultural negotiation, working with Canadians, Americans, Syrians, and British partners, all while operating as a Turkish company.

Beyond the practical business skills, this experience offered a profound lesson about the geopolitical forces that shape global business. The Syrian civil war has had a disastrous impact on its infrastructure and economy. We had witnessed Syria’s transformation from a thriving marketplace to a war-torn landscape, showing us how fast fortunes can change due to political instability and conflict. It taught us the need to continually reassess risk and stay informed about global events.

The relationship between peace and business was starkly clear. War not only devastates lives and societies, but it also disrupts and destroys economic activity. The only “beneficiaries” are the war traders and arms manufacturers who profit off the miseries of others.

In response to such a complex geopolitical environment, one must foster peace and stability. But at the same time, a nation must have the capacity to defend itself. This requires investment in technology and education to ensure a country’s military capability. This isn’t about promoting war, but about discouraging potential aggressors through the show of strength.

We returned from Syria, both enriched and sobered by our experiences. The contract, though profitable, was more than just a business venture—it was a lesson in adaptability, partnership, geopolitics, and the indelible link between peace and prosperity. The memories of this experience continue to influence our strategies and decisions, making us more resilient in an unpredictable global business landscape.