Mediating Russia–Ukraine War Risky Role For China – Analysis

By Ivan Lidarev*

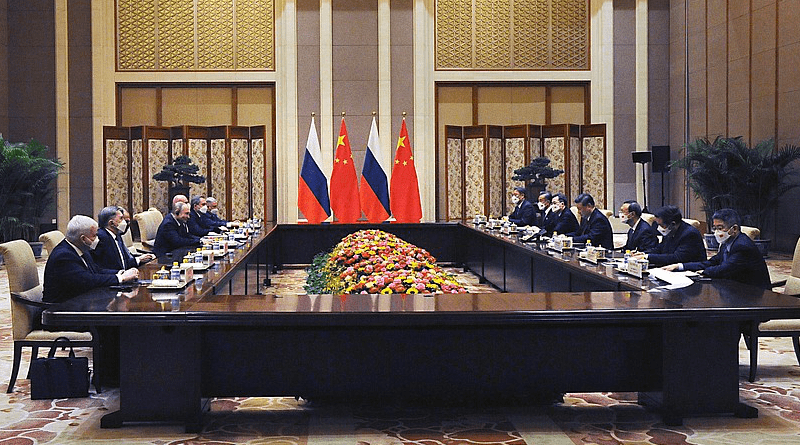

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, EU leaders, the Ukrainian foreign minister and French President Emmanuel Macron suggested that, as a neutral power close to Moscow, Beijing could mediate between Russia and Ukraine. Chinese President Xi Jinping himself vaguely spoke about a Chinese role in resolving the conflict in March and December 2022.

On the face of it, a Chinese mediation would seem to make sense for Beijing. It would improve China’s relations with the United States and Europe, which suffered massively as a result of Beijing’s stance on the war, present China as a peace-seeking world power and help end a conflict that destabilises the world economy and undermines China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

But China has been consistently reluctant to mediate between the two sides. The question is why.

Part of the answer is that neither Russia nor Ukraine is seriously interested in ending the conflict at this stage. The war also brings Beijing not only losses but gains — greater internationalisation of the renminbi, cheaper energy and a reduction of the US focus on the Indo-Pacific. China’s increasingly intense rivalry with the United States is yet another factor making an impartial Chinese mediation between US-supported Ukraine and anti-US and China-aligned Russia more difficult.

Beijing’s mediation would immediately put the spotlight back on China’s position of pro-Russian neutrality. China has consistently blamed NATO expansion for the conflict and taken pro-Russian political, rhetorical and mediapositions — all of which would draw renewed harsh criticism. This would reignite tensions with the West at a time when China is stabilising relations with Europe and trying to improve its beleaguered relationship with the United States.

China’s pro-Russian position would also raise doubts about Beijing’s status as a neutral mediator and might even derail its mediation efforts, especially if China proposes controversial compromises during negotiations. But abandoning these pro-Russian positions would be seen by domestic and international audiences as a humiliating retreat forced by Western pressure and Moscow would see it as a betrayal.

China also sees that mediating could easily turn into a Western push to force Beijing to sanction Russia. If Moscow resists ending the war or making substantial concessions in the negotiations mediated by Beijing, the West would likely blame China’s economic lifeline to Moscow for Russian President Vladimir Putin’s intransigence and the continuation of the war. The West, led by the United States, would exert massive pressure on Beijing to prove its commitment to ending the conflict by sanctioning Russia — pressure that would mount as the war continues.

In such a scenario, China would face a ‘lose-lose situation’. If it imposes sanctions it would alienate its only great power partner, losing in the process many of the recent high cost gains in China–Russian relations, and strengthen the position of its chief rival, the US, which aims to weaken Russia. If it doesn’t, it would further strain its tense relations with the West. Future progress in relations with the West might even become partlyconditioned on Beijing sanctioning Moscow. Both options would likely impose political and economic costs on China.

China also risks failure in its mediation effort. Compromises on the issues behind the war are extremely difficult to achieve, so mediation has slim chances of success. The only gain for China in a failed mediation effort would be to slightly improve its image in the West and briefly look like a responsible global power seeking international peace.

China’s losses in the case of a failed mediation attempt would be substantial. Beijing would look weak, diplomatically incompetent and unable to play the role of an international leader sought by President Xi — a point that its many detractors will exploit after China has suffered setbacks in its COVID-19 response and economic development. China would also look unable to manage Russia despite their progressively unequal relationship and be criticised for not using its leverage on Moscow.

None of this means that Beijing will refuse to mediate under any circumstances. It might do so at a later stage when the two sides are more willing to end hostilities and the international situation surrounding the war has changed.

Beijing might also be willing to take part in a multilateral diplomatic effort to mediate the war or facilitate dialogue between the two sides without mediation, in both cases reducing the risks of helping to end the conflict. China’s mediation calculus might also be influenced if Moscow asks Beijing to mediate or the war escalates catastrophically.

China is unlikely to mediate in the Russia–Ukraine war, at least until circumstances change significantly. In the meantime, Beijing will continue to make noises about mediating the conflict and restraining Russia to mollify the West.

*About the author: Ivan Lidarev is a foreign policy analyst and expert on Asian security and international relations, as well as a former advisor at Bulgaria’s National Assembly.

Source: This article was published by East Asia Forum