Philippines, The Pandemic And The President – Analysis

By Serena Dell’Angelo*

The year 2020 in the Philippines has been one of lock-down. The usually high-profile and energetic President Duterte has been relatively quiet, possible enjoying time off from international meetings and travels, activities that he evidently does not enjoy much. Instead, the focus has been on succession, settling internal scores, reinforcing its grip on power and, last but not least, securing his succession at the 2022 elections. Pundits still bet on his daughter, Sara Duterte, as the most likely successor.

Following the outbreak of Covid-19, on March 16th the Philippines started closing down by imposing one of the most severe lockdowns in the world. Comprehensive and severe measures were introduced and acronyms such as ECQ (Enhanced Community Quarantine) and MECQ (Modified Enhanced Community Quarantine) are now part of the colloquial language. Have the strict, protracted and strictly enforced measures worked in the fight against Covid-19? The answer seems to be no. The number of infected and dead, which by mid-September amount respectively to 269,407 and 4,663[1], continues to rise.

The viral outbreak is putting serious strains on a country with relatively weak structures. Most of the strains are borne by the low-income groups that now increasingly have to rely on government hand-outs. The pandemic and the measures taken by the government have caused the worst recession in more than three decades. The economy is tanking and unemployment has reached 10 percent (the rate has decreased in the last month after a spike in June peaking at 18 percent. The economic growth rate for 2020 is also expected to be negative, with the World Bank conservatively estimating a 1.9 percent decrease[2]. These factors are all fuelling public anger, including groups such as Jepneey and moto drivers that in the past were staunch supporters of the President. However, due to the measures imposed, the usual surveys of the government’s performance have not been published, so it remains to be seen how Duterte’s popularity is affected by his administration’s handling of the situation.

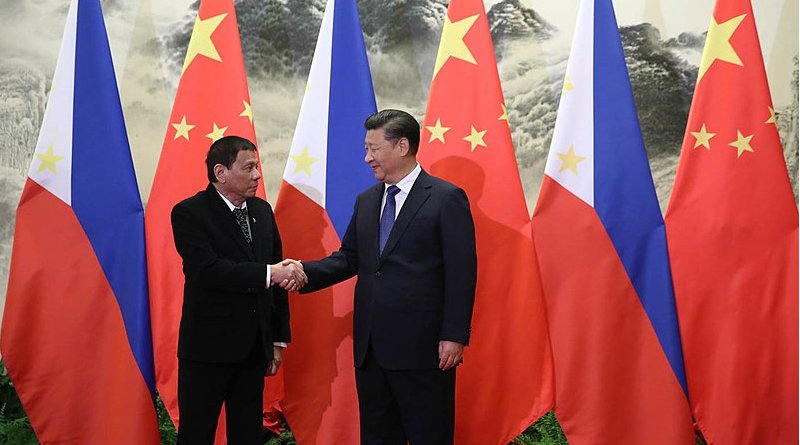

On the international stage, the South China Sea issue remains the dominant concern.

On July 13, the day after the 4th anniversary of the issuance of the award of the South China Sea Arbitration under UNCLOS, US Secretary of State Pompeo issued a clarification of the US position on maritime claims in the South China Sea[3]. The statement affirms that only the coastal states have a legal claim to the maritime resources in the area, apart from separate claims in the Spratley’s and Scarborough shoals that are limited to 12 miles within the relevant features. This clarification appears to pave the way for possible US sanctions against companies involved in exploitation by China of the maritime resources in the contested areas. It is also noteworthy that the US statement came at the tail of the June 26 ASEAN leaders’ meeting that failed to make progress on the South China Sea issue.

On July 12, Philippines’ Foreign Secretary Locsin issued a separate statement, which stressed the issue of maritime entitlements[4]. Philippine Defence Secretary Lorenzana issued a similar one[5].

The Chinese reaction was swift. On July 14, a video conference was held between the Philippine and Chinese foreign secretaries, stressing that “both states will continue to manage issues of concern and promote maritime cooperation and friendly consultation”. Within the Philippines, a further push-back was made by presidential spokesperson Harry Roque, who on the same day affirmed that the Philippines would not enforce the 2016 arbitration ruling.

The matter has been further compounded by the rejection of President Duterte of Locsin’s recommendation to end business deals with Chinese firms that built artificial islands in the South China Sea, based on the President’s belief that Philippines should continue to pursue a pragmatic cooperation with China. Furthermore, despite August 26th sanctions from the US commerce department towards 24 Chinese state-owned companies that participated in the Chinese militarization of the area, President Duterte issued a statement saying that the Philippines will not align with American directives, because it is a free and independent country, in need of Chinese investments[6].

The background for all these different statements concerning the South China Sea issues is of course the increased tension between the US and China. In the Philippines, instead, the developments illustrate the continued friction between US-leaning ‘traditionalists’ and China-leaning ‘pragmatists’. President Duterte is unlikely to change his non-confrontational stance on the South China Sea, but he may see some benefits in increased tension between the US and China on the issue, to the extent that such tension will lead to increased courting of the Philippines by both sides. However, it remains to be seen if in the longer term, the Philippines will be able to remain attractive for both super powers or if it will reach a point where choosing a side will become inevitable. A breaking point might be the US reaction if the Philippines actually were to begin to exploit their maritime claims, although this is unlikely to happen under Duterte.

Sadly, Duterte and his administration are continuing to settle scores with opponents, thus strengthening their grip on power. The national news channel ABN-CBS failed in getting its 25 years franchise renewed, because it was considered of being critical of the President, and is now expected to close down most of its operations. In June, the court presiding over the case against Maria Ressa, the founder of the media channel ‘Rappler’, ruled that the awarded journalist was guilty of cyber libel and now faces up to six years imprisonment[7]. The two incidents must be seen as the continuation of the pattern of intimidation of the media in the country. Media freedom has severely deteriorated under Duterte, who openly stated in 2016 “Just because you are a journalist, you are not exempted from assassination”[8].

Additionally, individual social media postings are now targeted for cyber libel, putting a heavy lid on critical comments about the government. Finally, a new Anti-terror law went into effect in July, which gives sweeping powers to the President to label, detain and eliminate government critics using a vague definition of terrorism.

All these developments that strengthen the President’s grip on power also have the effect of further shrinking the space for civil and political rights in the Philippines.

The deterioration of the human rights situation in the country has not gone unnoticed in the international arena. On the 16th of September, the EU Parliament approved a resolution[9] exposing the rise in human rights violations since President Duterte took office in 2016. These include, just to mention a few, widespread and systematic killings during the war against drugs, attacks against media freedom, the politically-motivated incarceration of Senator De Lima (who is still waiting in jail for trial since February 2017), and abuses on land-rights defenders and indigenous people. The EU Parliament’s renewed interest in the Philippines is undoubtedly also sparked by the case of Maria Ressa, and the generally deteriorating situation for the press in the country.

As a countermeasure, the elected legislative body of the European Union has threatened to revoke the trade benefits enjoyed by Philippines under the Generalised Scheme of Preferences Plus (GSP+), if the government will continue to fail to meet the requirements for the continuation of the trade privileges, which allows the Philippines to export 6200 products tariff-free to the EU.

However, it remains to be seen what the European Commission will put in place and which tangible consequences will follow from the EU threats, considering that the temporary withdrawal of the agreement is not easy to achieve.

However, if little or nothing will follow from the resolution, one can ask what is then the positive value of those instruments? They make a statement, sure, but then they bear little consequences, especially considering that they can easily be ignored by member states. A demonstration to that is the purchase by Philippines of 16 S-70i Black Hawk Helicopters from Poland. This is, in the word of the polish ambassador in Manila, an excellent example of cooperation between the two countries, which are ready to sign a memorandum of understanding covering the implementing agreement on Defence Cooperation[10].Moreover, the resolutions can have the effect of offending the partner country, thus further exacerbating the relations and make it even more difficult to push for reforms in line with the rule of law and the values of democracy. What is also worth consideration is the fact that the European Union is increasingly seen as a difficult partner in South East Asia; thus there is the need to shape a strategy on how to balance human rights issues with commercial interests. In the future, policy makers should consider that being more impartial in forming opinions and not coming across as superior or righteous is often the winning strategy for having an influence on partner countries.

The Philippines reaction to the European Parliament resolution has been prompt. Presidential spokesperson Harry Roque in an interview has dared the EU to ‘go ahead’ and to continue to threat the country during a pandemic that has already devastated Philippines and its economy at unprecedented levels. He also went on slamming the EU, calling it ‘the former colonial master’ and ‘the biggest contributor to the violation of the right to life of Filipinos if the trading privilege are to be revoked’[11].

To conclude, the Philippines’ response has been framed simply as ‘an enemy is threatening us during a crisis’. Thus, it appears to be in line with the continuation of the oldest narratives in politics, as well as geopolitics: ‘in times of crisis, find an enemy and blame it for your own misfortunes’.

*Serena Dell’Angelo is an independent human rights researcher.

[1] World O Meter, Philippines, Coronavirus Case, (17 September 2020), https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/philippines/.

[2] The World Bank, Philippines: Global Economic Prospects – Forecasts, (18 September 2020), https://data.worldbank.org/country/philippines?view=chart.

[3] Michael R. Pompeo, U.S. Position on Maritime Claims in the South China Sea, U.S. Department of State, (13 July 2020), https://www.state.gov/u-s-position-on-maritime-claims-in-the-south-china-sea/.

[4] Locsin, Teodoro L. Jr., Statement of Secretary of Foreign Affairs Teodoro L. Locsin, JR. on the 4th Anniversary of the Issuance of the Award in the South China Sea Arbitration, Philippines Department of Foreign Affairs, (12 July 2020), https://dfa.gov.ph/dfa-news/statements-and-advisoriesupdate/27140-statement-of-secretary-of-foreign-affairs-teodoro-l-locsin-jr-on-the-4th-anniversary-of-the-issuance-of-the-award-in-the-south-china-sea-arbitration.

[5] Lorenzana, Delfin N., Statement of the SND on the US Position on Maritime Claims in the South China Sea, Philippines Department of National Defense, (14 July 2020), https://www.dnd.gov.ph/PDF2020/20200714%20-%20Statement%20of%20the%20SND%20on%20the%20US%20Position%20on%20Maritime%20Claims%20in%20the%20South%20China%20Sea.pdf.

[6] Robles, Raissa, “South China Sea: Duterte Rejects Call to Drop Contracts with Chinese Firms”, South China Morning Post, (1 September 2020), https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/3099793/south-china-sea-duterte-rejects-call-drop-contracts-chinese.

[7] Ratcliffe, Rebecca, “Journalist Maria Ressa found guilty of ‘cyber libel’ in Philippines”, The Guardian, (15 June 2020), https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jun/15/maria-ressa-rappler-editor-found-guilty-of-cyber-libel-charges-in-philippines.

[8] Reuters Staff, “Philippines’ Duterte denounced for defending killing of some journalists”, Reuters, (1 June 2016), https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKCN0YN3TK.

[9] European Parliament, Joint Motion for a Resolution on the situation in the Philippines, including the case of Maria Ressa, (2020/2782(RSP)), https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/RC-9-2020-0290_EN.html?fbclid=IwAR3rpnRHz7n-o_QdV_wv3_REI1wWhhs67JzmzGCw_RlvjFpGDNQGwYGaYzY.

[10] Szczepankiewicz, Jaroslaw, “Poland stands with PHL in defense, development”, Business Mirror, (10 June 2020), https://businessmirror.com.ph/2020/06/10/poland-stands-with-phl-in-defense-development/?fbclid=IwAR1s8KHJDmjII_dO_63FIGu7EbNMEoti_Z2Q9ahuNDPvIg1D6aXSxKQrDiY.

[11] Chiu, Patricia Denise M., “EU Parliament threatens to revoke PH trade perks”, Philippine Daily Inquirer, (19 September 2020), https://globalnation.inquirer.net/191001/eu-parliament-threatens-to-revoke-ph-trade-perks.