‘Not Doomed’ But Uncertain: What Does The New US House Speaker Mean For Aid To Ukraine? – Analysis

By RFE RL

By Reid Standish

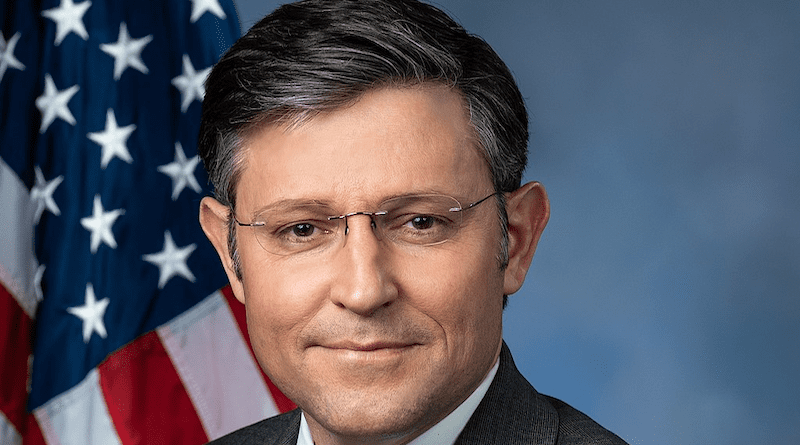

(RFE/RL) — After 22 days of legislative chaos in the U.S. House of Representatives, Republican Mike Johnson — a little-known lawmaker from Louisiana — became speaker of the lower chamber of Congress on October 25, reflecting a rightward shift by his party that raises new questions over the future of U.S. aid for Ukraine.

The new speaker inherits a slew of looming policy deadlines, including a potential government shutdown on November 17, but attention has quickly turned to how Johnson will approach a sweeping, nearly $106 billion package that U.S. President Joe Biden sent to Congress. It includes some $60 billion in assistance for Ukraine and $14 billion for Israel, as well as funding for security in the Indo-Pacific and enforcement on the U.S. border with Mexico.

Before becoming speaker, Johnson previously voted against aid to Ukraine, joining some other House Republicans who argue that the money could be better spent at home and that the United States should not be so deeply involved in overseas conflicts.

One day after being elevated to his new role, Johnson once again expressed concerns over Ukraine funding during a Fox News interview on October 26 and said that aid for Ukraine and Israel should be handled separately, suggesting he will not back the White House’s $106 billion aid package in its current form.

“Israel is a separate matter — we are going to bring forward a standalone Israel funding measure [of] over $14 billion,” Johnson said in the interview.

“We can’t allow [Russian President] Vladimir Putin to prevail in Ukraine because I don’t believe it would stop there,” Johnson continued, but he called for greater scrutiny on aid for Ukraine as Russia’s full-scale invasion has passed the 20-month mark with no end in sight.

“We want to know what the object is there, what is the endgame in Ukraine,” Johnson said, echoing calls from various quarters for a clearer explanation of U.S. goals. Biden has said the United States will support Ukraine for “as long as it takes,” but some on both sides of the debate over aid for Kyiv want more details.

What does Johnson’s election mean for U.S. assistance for Ukraine, a crucial element in Kyiv’s efforts to defend itself and drive Russian forces from the country?

Experts who spoke to RFE/RL said that they expect a tough legislative road ahead, but that bipartisan support for Kyiv is still strong across Congress.

“Johnson as Speaker does not doom Ukraine aid, though it may complicate the overall process toward getting a vote on the $60 billion package,” Andrew D’Anieri, a resident fellow at the Washington-based Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center, told RFE/RL.

Here’s what we know so far — and what analysts are watching as Johnson settles into his new position as speaker for the 435-member House.

Who Is Mike Johnson And What Are His Views On Ukraine?

Shortly after Johnson’s election as speaker on October 25, he held back on his views regarding Ukraine, making no mention of the country or Russia’s war against it in remarks in which he emphasized, “We stand with our ally Israel.” When a reporter asked whether he supports additional U.S. aid to Ukraine, he said he would not talk about policy and another Republican lawmaker at his side loudly urged the journalist to “go away.”

Prior to that, Johnson — a lawyer who also played a leading role in former U.S. President Donald Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election – has walked an unclear line toward Ukraine since Russia launched its full-scale invasion on February 24, 2022.

He came out forcefully in support of Kyiv later that day, saying in a statement that Moscow’s invasion “constitutes a national security threat to the entire West.”

He also called for “debilitating sanctions” against Russia and concluded that “America’s prayers remain with the Ukrainian people.” In April 2022, Johnson voted in favor of legislation that made it simpler for Washington to supply weapons to Ukraine.

But in May and December 2022 and in September 2023, Johnson voted against appropriations that included aid to Ukraine.

He has argued for more accountability due to transparency and corruption concerns with Ukraine handling U.S. taxpayer money, echoing statements by some other prominent Republicans, such as then-speaker Kevin McCarthy, that Kyiv should not be granted a blank check.

“They deserve to know if the Ukrainian government is being entirely forthcoming and transparent about the use of this massive sum of taxpayer resources,” he said in February of this year.

This — in addition to Johnson’s comments since becoming speaker — have raised questions about the level of support toward Ukraine that can be expected from Republicans in the House under Johnson.

How Has Ukraine Responded?

Kyiv is looking to shrug off the political jostling on Capitol Hill. Oleksiy Danilov, secretary of Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council, welcomed Johnson’s election as an end to the stalemate in Washington and said in televised comments that he was “more than sure that cooperation will continue, assistance will continue.”

Danilov seized on a separate comment in which Johnson, when asked on October 25 whether he supports more aid for Ukraine, told reporters: “We all do…. We are going to have conditions on that so we’re working through.”

“The statement made by the speaker that they would like to check the assistance they provide — this is a completely natural thing,” Danilov said. “We’re happy to provide all information about the aid, there are no secrets.”

A “report card” issued by a Republican group that advocates continuing support for Ukraine gives Johnson a “very poor” rating based on his votes and public comments since the full-scale invasion.

Two of the three Republicans who made unsuccessful bids to become House speaker before Johnson was nominated have been more supportive of Ukraine – which may have hurt their chances because of the stance of hard-right lawmakers such as Matt Gaetz, who led the push to oust McCarthy from the speaker post.

McCarthy’s ouster on October 3, unprecedented in U.S. history, complicated the Biden administration’s efforts to secure new aid for Ukraine.

Four days later, the massive attack on Israel by the Palestinian militant group Hamas added a major new factor, sparking a new Middle East war that has diverted attention from Ukraine and created a potential competitor for urgent U.S. aid.

The Atlantic Council’s D’Anieri said that Johnson’s past voting record may not be a straightforward rubric for how he will approach Ukraine as speaker, noting that previous aid packages made it through the House with significant bipartisan majorities and Johnson had not faced pressure over the direction of his past votes.

“After winning the speakership, Johnson told reporters that he’s willing to support aid with conditions and talks with the White House on ‘accountability and [clear] objectives,’” he said. “Now he’ll have to make good on those promises, but they may not be such a bad thing [for Ukraine] if he pushes both of those in good faith.”

Will Ukraine Be Able To Get Its Funding Approved?

Combining aid to Ukraine in a single package with $14 billion in support for Israel, as well as money for Republican-backed causes such as border security, is an attempt by the White House to convince House Republicans wary of sending additional money to Ukraine and increase the legislation’s chances of approval.

On October 25, Biden congratulated Johnson and said it was “time for all of us to act responsibly” and adopt a measure to avert a U.S. government shutdown next month, as well as providing aid for Ukraine and Israel.

In his interview with Fox, Johnson has now signaled he intends to split Ukraine funding from that of Israel in the proposed funding package, setting up a legislative battle over the coming month.

But doing so will also expose divides within the Republican Party itself over Ukraine.

“Republicans in the House are divided over this, but most Republicans in the Senate generally support continuing the assistance to Ukraine,” John Deni, a research professor at U.S. Army War College, told RFE/RL. “They understand that Ukraine is dramatically degrading the land power of one of the United States’ two major adversaries in the world.”

Deni added that given high support among Democrats in the House and Senate for Ukraine aid, it’s still likely that the package of military assistance to Kyiv will be bundled with other legislation.

However, with a potential government shutdown in November a real possibility, any future scenario is difficult to predict, and analysts expect tough political battles ahead.

D’Anieri said that it was still unclear whether Johnson could succeed in separating Ukraine and Israel funding from the same bundle, and that Johnson probably could not have won the speaker’s post without assuaging more moderate Republicans who support aid to Ukraine.

“The fact that the entire caucus [of Republicans in the House] rallied around the ultraconservative Johnson suggests that moderate members received major assurances of some kind,” he said.

D’Anieri added that bipartisan support for both Ukraine and Israel remains high, including from Democratic Senate leader Chuck Schumer and Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell.

“A split funding bill would be dead on arrival in the Senate,” he said. “So Johnson will face huge pressure from many in his own caucus, Senate Republicans, and the White House to pass a joint Ukraine-Israel spending bill. It will be tough for Johnson to push back against them.”

Steve Gutterman contributed to this report.

- Reid Standish is an RFE/RL correspondent in Prague and author of the China In Eurasia briefing. He focuses on Chinese foreign policy in Eastern Europe and Central Asia and has reported extensively about China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Beijing’s internment camps in Xinjiang. Prior to joining RFE/RL, Reid was an editor at Foreign Policy magazine and its Moscow correspondent. He has also written for The Atlantic and The Washington Post.