Anarchy In The European Union? – Analysis

By Published by the Foreign Policy Research Institute

By Ronald J. Granieri*

(FPRI) — This is a historic week for Europe, for better or worse. On March 25, the members of the European Union gathered in Rome to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Rome. That historic document created the European Economic Community, the community of six which embraced the desire for “Ever closer union” and which eventually grew into the 28-member EU of today.

In Rome, the assembled presidents and prime ministers pledged to redouble their efforts to advance European unity. Donald Tusk, President of the European Council, referred to his Polish roots in reminding his audience of Europe’s history of division and the hopes for unity that continue to animate the organization, despite its manifest weaknesses and current troubles. “I am recalling this brief course in history today,” Tusk announced, “only to make everybody aware that for millions of people, and today those millions will be demonstrating in the streets of our capitals, in Rome, in Warsaw, even London, the European Union is not about slogans, it is not about procedures, it is not about regulations. Our Union is a guarantee that freedom, dignity, democracy and independence are no longer only our dreams, but our everyday reality.”

In a joint declaration, the participants of the conference committed themselves to the European project even as the EU faces “unprecedented challenges.”

What challenges, you ask? Well, that leads us to the other historic aspect of this week in Europe.

You see, not all of the EU’s members were present in Rome. Conspicuously absent was UK Prime Minister Theresa May, who was busy back in London drafting Britain’s divorce petition from the EU. Following through on the Brexit referendum vote of June 2016, and after months of parliamentary wrangling, Britain is now ready formally to invoke Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty, which lays out the mechanisms for a member state to leave the EU. However the negotiations on their future relationship turn out, according to the two-year timetable foreseen by Article 50, the UK will cease to be a member of the EU on March 29, 2019.

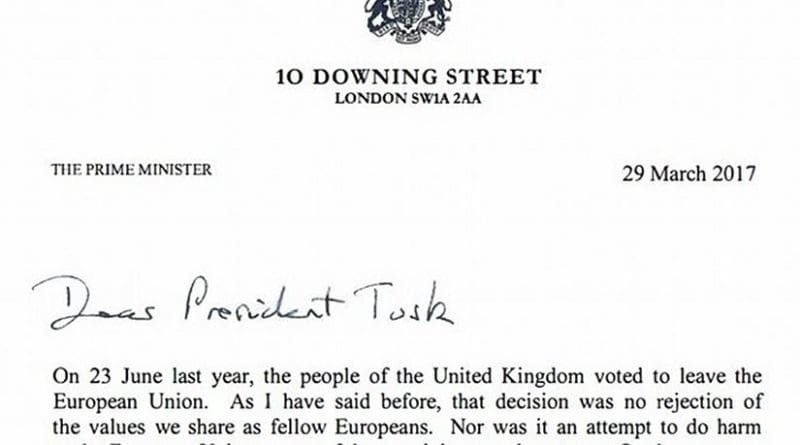

May’s 5-page letter to President Tusk was hand-delivered by Britain’s Permanent (for the moment) representative to the EU, Sir Tim Barrow (not, as some may have hoped, strapped to a Bulldog smoking a Churchill cigar flying a Spitfire).

In her opening paragraph, the PM tries to strike a firm but conciliatory tone, declaring that the Brexit vote

was no rejection of the values we share as fellow Europeans. Nor was it an attempt to do harm to the European Union or any of the remaining member states. On the contrary, the United Kingdom wants the European Union to succeed and prosper. Instead, the referendum was a vote to restore, as we see it, our national self-determination. We are leaving the European Union, but we are not leaving Europe – and we want to remain committed partners and allies to our friends across the continent.

That respectful tone remains consistent throughout, as May announces that her government “wants to approach our discussions with ambition, giving citizens and businesses in the United Kingdom and the European Union – and indeed from third countries around the world – as much certainty as possible, as early as possible.” The principles she sketches for negotiations are based on a confidence that the UK and its twenty-seven soon-to-be-former partners should be able to reach an agreement that allows them to separate amicably and work together profitably thereafter.

At the same time, the letter includes a reference to a particularly British problem. As May carefully puts it: “From the start and throughout the discussions, we will negotiate as one United Kingdom, taking due account of the specific interests of every nation and region of the UK as we do so.”

That’s a bold statement, considering that the United Kingdom is far from united on the question of Brexit. Although Brexiteers celebrate their referendum victory as the last word on the subject, and dismiss the forty-eight percent who reject Brexit as “Remoaners,” it remains to be seen exactly how the UK electorate will adjust to a post-EU reality.

Moreover, it remains to be seen how united the United Kingdom will be. Prime Minister May will use her March 29 speech in Parliament to call upon Britons to “come together” in support of the new relationship, but she is facing significant questions. The Scots, who voted nearly two-to-one to Remain in the EU, are toying with a new independence referendum of their own. Even if the EU, with an eye toward potential secessionist regions in other member states (such as Spain’s restless Catalonia), does not want to encourage the breakup of any European state, it’s not hard to imagine Brussels using disunity across the Channel to drive a harder bargain.

Also problematic is the border between Northern Ireland (which along with Scotland also voted to remain in the EU) and the Irish Republic, which would become the one hard land border between the EU and a post-Brexit Britain. May specifically mentioned the need to maintain the gains from the Northern Irish peace process (of which the EU is a key guarantor) in her letter to Tusk. But others have speculated that Brexit might be the moment for the estranged parts of the Emerald Isle to reunify at last. If the Irish were to take that step, London would be legally bound by 1998’s Good Friday Agreement to recognize it.

Thus, the fragmentation begun with Brexit may not end at the Channel.

That’s a long shot, but then again, so was Brexit.

So, mark your calendars. March 29, 2017 looks to go down in history as the end of the preliminaries and the start of Brexit as a reality. How one will feel about that date in the future depends, of course, on how one feels about the breakup of the European Union and about the future shape of a not-quite-United Kingdom.

To help them manage any anxieties they may feel, Brexiteers can welcome a new celebrity on their side. John Lydon, more famous as Johnny Rotten of the punk legends The Sex Pistols, recently announced his support for both Brexit and Donald Trump. At first blush, the punk rocker may be a strange bedfellow for a Tory Prime Minister. Then again, both of them seem to be willing to risk anarchy in the UK—at least for the next two years.

About the author:

*Ron Granieri is the Executive Director of FPRI’s Center for the Study of America and the West, Editor of the Center’s E-publication The American Review of Books, Blogs, and Bull, and Host of Geopolitics with Granieri, a monthly series of events for FPRI Members.

Source:

This article was published by FPRI