North Macedonia Fugitive PM’s Pious Project Ends In Bankruptcy – Analysis

Nikola Gruevski intended a grandiose church in the centre of Skopje to showcase his power and piety – but now he is a fugitive in Hungary and his abandoned church is the subject of bankruptcy proceedings.

By Sinisa Jakov Marusic

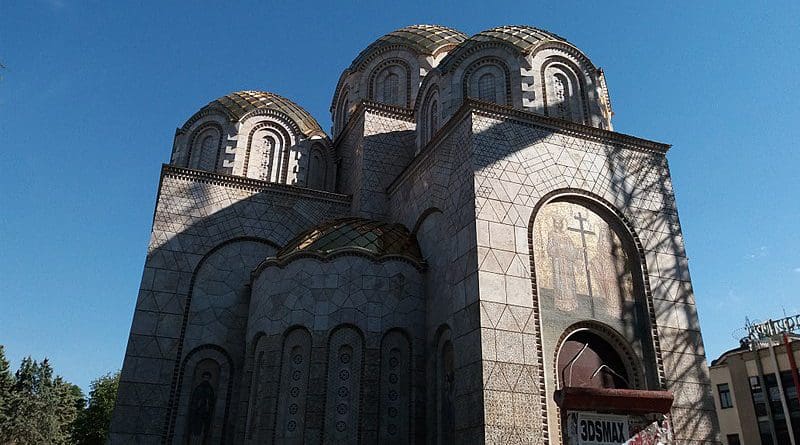

Exactly eight years after its construction started in 2012, the Macedonian Orthodox church of Sts Constantine and Helena, which was originally planned to be finished in three years, in the heart of North Macedonia’s capital, Skopje, remains incomplete.

In contrast to the political and ethnic furore it generated in the past, the construction site now lies silent and abandoned.

Promoted with much pomp to showcase the piety of the now fugitive prime minister, Nikola Gruevski, and his socially conservative VMRO DPMNE party, the church, nicknamed “Gruevski’s Church”, may soon become the first religious object in the country ever to become part of bankruptcy proceedings.

It would also be the first time the Macedonian Orthodox Church has appeared in the role of debtor in a bankruptcy procedure sought by the construction firm, Beton, which built it and now wants its 1.1 million euros’ payment.

Harbinger of city’s divisive makeover

The erection of the controversial church foreshadowed the bigger and much more divisive government project to revamp the entire capital in classical style, known as “Skopje 2014”, which was first revealed in CGI in a government video in 2010.

Although the church controversy predates “Skopje 2014” by some years, the building was included in the “Skopje 2014” promotional video, so becoming an informal part of it.

The row began in 2009, when the VMRO DPMNE-led government first revealed the plans to build a big church on Skopje’s main square.

Despite bearing no resemblance to it, it was presented as a renewal of an old church of the same name that had existed nearby but which was demolished in 1970s, after being damaged in the massive 1964 earthquake.

In March 2009, architecture students protested against the plan to put up a new church on the square, where it would obstruct pedestrian traffic. In violent scenes, a large crowd of church supporters carrying flags and crosses attacked the protesters.

Soon after, the country’s second largest faith group, the Islamic Religious Community, also cried foul, demanding that the state also help rebuild an old mosque that had also lain near the main square in Ottoman times.

Following the prime minister’s insistence that the church would be built no matter what, it was initially referred to as “Gruevski’s Church”.

As friction mounted between the Orthodox Church and mainly Albanian Muslims, and as arguments about government interference in religious matters failed to subside, the government compromised.

To avoid further uproar, that year the authorities donated the site to the Macedonian Orthodox Church, so that it, not the state, would appear formally as the investor.

In another compromise made in 2012, the location of the church was shifted several hundred metres from the main square to its current location, in what was previously a small park near the main pedestrian thoroughfare, Macedonia Street, metres from parliament.

In 2013, the church was again at the centre of violence when an angry pro-government mob attacked the premises of the municipality of Centar, which had just elected a new mayor from the ranks of the then opposition, and who was a strong critic of the Skopje 2014 project.

Mayor Andrej Zernovski barely escaped with his life from the angry mob, which was convinced he was about the scrap construction of the church – which he denied.

A court in September this year sentenced ex-PM Gruevski to a year-and-a half in jail for inciting the mob attack under a false pretext.

Construction of the church then began in the presence of Gruevski himself in 2014, amid many still unanswered questions about its cost and the source of financing.

Backed politically – and shrouded in secrecy

Strongly backed by the then main ruling party, albeit in an informal manner, the project gained traction.

In 2012, the Transport Ministry sold the new site to the Macedonian Orthodox Church for a bargain price. It paid only 65,000 euros for 2,230 square metres on which the park was formerly located.

The Church then formed a foundation that was formally tasked with gathering donations and overseeing construction.

MPs that year donated a million euros to the foundation to start the preparations.

As construction began in 2014, media sought any information they could get regarding its cost and funding.

But the government insisted it had nothing to do with the project, while the Macedonian Orthodox Church redirected inquiries back to the foundation, which proved extremely hard to reach.

Despite all of this, things moved on. The first donation of a million euros came from the Macedonian Orthodox Church itself, and three consecutive donor conferences, broadcasted live on TV, in 2012, 2013 and 2014, raised more funds.

Incentivised by the then ruling party, which seemed to be gaining in popularity, the business sector also flocked to help.

The list of donors obtained in 2018 by the Investigative Reporting Lab Macedonia, IRL, from the Justice Ministry, one year after VMRO DPMNE was ousted, showed that almost all the top businesses had donated cash, amounting to some 2 million euros.

Even state-owned institutions and enterprises donated. The state-owned electricity transmission system operator, MEPSO, donated 66,000 euros, and the state-owned forest reserve gave another 3,200 euros, data obtained by IRL showed. Even the state-owned news agency, MIA, donated a modest 100 euros.

Records from the Revenue Office show that in 2012 the foundation received only the million euros had received from the Macedonian Orthodox Church. In 2013, it gathered 1.65 million euros and in 2014, 700,000 euros.

But as the country plunged into a political crisis sparked by Gruevski’s authoritarian ways, and as his once tight grip on power weakened, donations for the church fell sharply.

In 2015, as the political crisis deepened, the foundation received only 280,000 euros, and in 2016 this fell again to 28,000 euros and by 2017, one year before Gruevski was toppled, donations amounted to a tiny 160 euros.

Silence broken finally by court demand

For a long time, the church fell out of the public focus. The silence was only interrupted in November, when media reported that the company hired to construct the church, Beton, from Skopje, had filed a demand to the Skopje Basic Court for a bankruptcy procedure, citing unpaid debts of 1.1 million euros.

The demand was filed in September and the court had already appointed a bankruptcy trustee, the court revealed. Beton had asked for the church as well as the land on which it is built to be part of the bankruptcy estate.

The court hearing at which the fate of the church would be decided was initially set for November 11. But this was later postponed, as has happened frequently during this year of health crises. The hearing will now have to wait for 2021.

The construction site has been practically dormant since 2017. Externally, the lavish façade seems almost finished and its almost 50-meter bell tower dominates the surrounding area. But the entire site is off limits to the public, as it is fenced off.

“It may seem almost finished but there are many fine details inside that still need to be done, like the frescoes, the floor and all sorts of installations. The bell tower needs more work as well,” one Macedonian Orthodox Church employee, who was a former member of the foundation that built the church, told BIRN under condition of anonymity. He insisted he had not played a big role in it and no longer wants to be associated with the project. He defended it, however.

“Everything was transparent. We worked in a legal manner and were driven by the wish to see the church done,” the source insisted, asked why the now practically defunct foundation was so secretive.

“We did not want to expose ourselves too much as the Macedonian Orthodox Church was in charge of that part. That was not our job. We had a different task to do, so we focused on that,” he explained.

He added that he did not know the total cost of the current build, but his estimate was that “it would take 2 to 3 million euros minimum to complete it”.

Back when construction started, the secretive foundation mainly comprised civilians, including lawyers and small businessmen who were not very prominent publicly, as well as several priests and Church employees. Then, as now, most of them were hard to reach for information.

The Macedonian Orthodox Church has also offered no comment about its plans for the church or the bankruptcy procedure it is now involved in.

“Perhaps the whole thing was overly politicized. It should have been left to people’s good will to donate,” said the only source who was involved that BIRN could reach.

“Gruevski wanted to do something good and leave some heritage behind, as many did before him, but the Macedonian Orthodox Church should have relied more on itself, not on the politicians who are changeable, for help.

“In typical Macedonian fashion, we started something and failed to finish it.”

Neither the city of Skopje nor the Centar municipality seem to have much of a plan for the future. Both said they could not comment on court matters that concern private property.

Tightly linked in a negative way with Gruevski, who now has political asylum in Hungary, the current Social Democrat-led government is unlikely to wish to stick its fingers into this complex affair either.