The Reality Of Singapore’s Chinese Privilege – OpEd

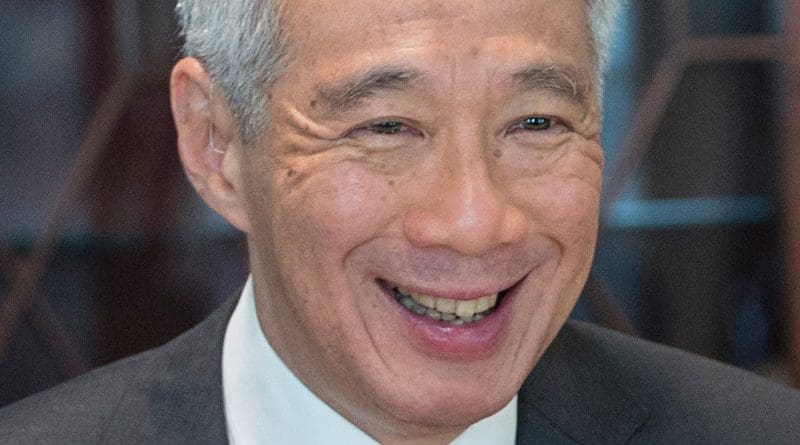

During his National Day Rally on 29th August 2021, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong took the opportunity to argue that there is no Chinese privilege in Singapore. According to Hsien Loong, the claim that there is Chinese privilege is “entirely baseless”.

He is not alone in making such claims. Other commentators have similarly argued that there is no Chinese privilege. In January, academic Mei Lin Fung disputed the existence of Chinese privilege. She suggested that its use is a misappropriation of White privilege as is commonly discussed in the west.

However, when she finally conceded that there is privilege for the Chinese in Singapore, she suggested we use the term “majority privilege” instead.

Why are the Chinese so against admitting that there is Chinese privilege? To be sure, not every Chinese Singaporean deny the existence of privilege. There is now, greater recognition among Singapore commentators and activists that the Chinese are indeed, privileged.

There are several reasons for the non-admission of privilege.

1. It creates a negative self-image of themselves. To admit privilege is an admission that they have not been fair to the other ethnicities.

This is a normal human desire. You want to believe that you are good. That you are just. And the same value that you ascribe for yourself is what you believe of your community.

When I was a Research Fellow at Monash University some years ago, there was a young PhD student from China in my department. We discussed politics at times. He knew of Lee Kuan Yew but not well enough to have a discussion.

I described how Lee Kuan Yew is a racist and the systemic racism in Singapore. He was troubled by it. He could not accept that racism existed in Singapore.

And the reason for his rejection? He said that the Chinese have been discriminated everywhere in the world. They have experienced racism.

For him, it was impossible for the Chinese to be racist given their experience.

2. To admit that the Chinese are privileged will cast doubt into their achievement and the underachievement of other communities, especially the Malays.

If the Chinese are privileged as an ethnicity, can they truly lay claim to meritocracy for their continued wealth , success and power? How much of what the Chinese community has is due to their intelligence and hardwork and how much is the result of privilege? Can they truly claim they deserve what they have?

3. The PAP’s claim to legitimacy is based on an idea of racial equality. They argued that the reason Singapore was booted out of Malaysia was because the Malays in Malaysia sought dominance of the Malays while the PAP demanded a Malaysian Malaysia where everyone was equal.

To admit that the Chinese are privileged calls to lie the claim of racial equality that the PAP claimed is their foundational position.

What is privilege?

There are some Chinese who argued that they have never felt privileged or have never benefited from being a Chinese. Lee Hsien Loong made similar spurious comments when he rejected the claim of privilege.

According to Lee Hsien Loong, the Chinese community accepted English as the lingua franca of Singapore instead of a Chinese dialect to put the minorities at ease. That is supposed to be an argument against privilege.

How silly.

No, that is not an argument against privilege. That is an admission that there is privilege.

To argue that you are able to make it worse for the other communities, is an admission that you have the power to do it. That the Chinese accepted English to put the other communities at ease is an acknowledgement of Chinese privilege to define and decide which language is used.

Can an Indian make that comment?

Can the Indian community argue “We decided to accept English instead of using Tamil as the lingua franca to put the other communities at ease”? Of course they could not. Because everyone knows that the Indians, Malays and other ethnicities making those statements would have no effect.

Only the Chinese could make that statement and mean it.

As has been often pointed out, privilege does not mean every Chinese individual will benefit. What it means is this:

1. There are no or less obstacles for the Chinese as a community than there are for non-Chinese.

2. It refers to systemic privilege and power to decide.

Let me give a few examples.

Most policymakers such as Ministers and top bureaucrats are Chinese. A number of them come from Chinese schools with very little interaction with non-Chinese. When they craft policies, they view these policies from the perspective of the Chinese.

Such behaviour is found at every level of government and society. From the government’s drive to sterilise the lower-income Singaporeans to ensure they do not reproduce (which targets the non-Chinese communities) (Li, 1989, pp.114-115) to how schools timetables tend to be designed against Malay students.

Tania Li (1989, p. 119) reported that bureaucratic stereotype, which is a symptom of institutionalised racism, exacerbated the problems of Malays in education. “Given the tendency to prejudice and stereotyping…many Malay students, parents, and leaders have found that classes in which Malays predominate are treated differently from those comprising Chinese and other ethnic groups. For example, a Malay boy who achieved the top grade in science in his class was forced to take technical studies instead of science because the timetable was not arranged to allow students taking Malay to also take science”.

The teachers and officers who designed such timetables may not have intentionally decided to be racist. But in drawing up the timetable from their perspective, it made sense for them, for their ease, to create timetables that move Malay students to technical subjects rather than science.

Would a Malay or Indian policymaker and teachers have crafted similar sterilisation or timetabling policies? The point is that those in positions of power, who have the ability to decide on the policies are Chinese. While they may not intentionally decide to be racist to the other races, they look at issues from the perspective of a Chinese.

It is also instructive that a large number of issues that affects the Chinese community are treated as national issues. While similar concerns from the Malay, Indian, Eurasian communities do not get the same concern or support.

For example, the Speak Mandarin campaign receives wide, national coverage. That the Chinese community has lost their connection to the Mandarin language was promoted as a national cause, even if it was not claimed to be one. Nevermind the fact that the Chinese in Singapore had never had real connection with Mandarin.

But the support for Mandarin and its advertisement was a common national concern.

And yet, the Malay language had similar problems. A lot of Malays have lost connection with their language. But it is not promoted nationally. There are the promotion for the (correct) use of the Malay language, but these promotions are confined to the Malay community.

Of course, it can be argued that there are more Chinese, hence their concerns are nationalised.

And that is exactly the argument for the existence of Chinese privilege.

Chinese privilege can also be seen in how the Chinese community are absolved when there are conflicts with others. In the 1960s, there were a couple of race riots between the Malays and Chinese.

Both parties were at fault. And yet, only one was punished.

When the PAP government instituted National Service in 1967, Malay youths were not called up. But it was not declared that they would not be called up for service. As a result, for about 10 years, Malay youths were in limbo, unable to carry on with their studies or gain employment because of expectation of being drafted. This led to the suppression of the Malay community and their socio-economic growth.

In 2001, in his attempt to justify the policy that caused such hardship to the Malays, Lee Kuan Yew said, “In the early days, many Malay Singaporeans were not called up for NS. When NS started in 1967, race relations were fragile and tenuous, after the riots of 1964 and separation in 1965. The government could not ignore race tensions, simply recruit all young Malays and Chinese and have them do military training side by side.”

The question for us is this: if the Chinese and Malays rioted against each other, then why were the Malays the only ones punished?

Why not the Chinese community too?

During the 1960s, the PAP claimed that the biggest threat to Singapore’s security were the communists. The communists were mainly Chinese.

And yet, the Chinese youths, who would have represented the supposed security threat and were involved in racial riots were not punished.

The Malays were.

I am not advocating for the Chinese to be punished. My argument is that because Lee Kuan Yew is Chinese and the system was and is controlled by the Chinese, there is a preference and privilege accorded to the Chinese.

Chinese privilege is an undeniable reality. You may deny it. Call it majority privilege or any other euphemism.

It does not detract from the fact that there is Chinese privilege in Singapore.

*Zulfikar Shariff lives in Australia and writes about Islam, politics and international relations. He writes at www.fitrahmedia.com

Reference:

Li, T. M. (1989). Introduction to Malays in Singapore: Culture. Economy and Ideology. Oxford University Press.

Privileged Malay families sent their kids to universities in Singapore without paying tuition fees. They saved the money to buy cars! We don’t see any Chinese complain about that! We all have different privileges and that is fair because of different circumstances. The important thing is we are all friendly towards one another because we understood where we came from and accepted that.