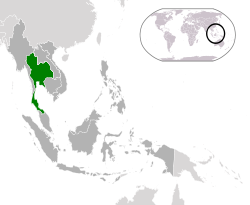

Thailand: Long-Term Peace In South Only Through Space For Insurgents – Analysis

In order to bring an end to the violence and and bloodshed that has been plaguing Southern Thailand for nearly eight years, it is absolutely pivotal that insurgency groups be encouraged to organise politically and come to the negotiating table as soon as possible.

By Timothy Williams

Secessionist impulses in Southern Thailand have existed since the Sultanate of Patani was formally included in the Siamese Kingdom in the early 20th century, but violence returned to the region in January 2004. Today, the violence shows no signs of abating and continues on a daily basis with assassinations and bombings of government employees, military personnel and civilians, and the destruction of regional infrastructure. Since 2004 over 5,000 people have died and 8,000 have been injured, a majority of whom were civilians. Also, human rights abuses by insurgents are steadily increasing in both quantity and intensity.

The aim of the insurgency

The main organisation operating today is thought to be BRN-Coordinate (Barisan Revolusi Nasional- Coordinate), which was formed after splitting from the BRN in the 1980s. This very loosely structured and hyper-secretive group does not take credit for any of its attacks, and has also refrained from issuing any concrete demands or stating clear and negotiable goals. The general aim, however, appears to be merdeka – the Malay word for sovereignty or independence – for the territory of the former Sultanate of Patani, although some factions of the movement may settle for autonomy within the Thai state. The insurgency cannot be seen as a cry for development or a better standard of living, but it feeds off a sense of Malay nationalism rooted in the Patani homeland – altogether this creates a sense of being ruled by foreigners and undermining the Patani national right to self-determination.

Military response so far inadequate

The policy for bringing peace to the South so far has been to try and suppress the insurgency militarily, combined with an increase in development of the area. This strategy has been and is doomed to be unsuccessful, simply because it does not pay enough tribute to the real situation. Investing in development is always good, but will not bring peace as it assumes that the violence springs from economic dissatisfaction, not recognising the genuine desire for cultural recognition and a degree of autonomy.

Further, while in past decades, when insurgents were camped in the jungle and launched coordinated attacks from there, a military approach may have been useful, today’s cellular structure is embedded in everyday village life with volunteers not fighting full-time but well integrated into their surroundings. Intervention, thus, always effects the lives of non-participating civilians, too; rather than undermining the insurgency, this military response can even feed the grievances of the population and raise support for the insurgency.

It is necessary for a regional dialogue to emerge on possibilities of autonomy or special governance structures for the South, and to this end the Thai government must try and facilitate the openness of dialogue. Actors in the South must be able to engage in a dialogue without fearing accusations of being traitors – only through creative, open and honest discourse will it be possible for a solution to emerge which a majority is happy with.

BRN-C structure undermines potential for negotiation

All organisations in the insurgency are so cellular that not only is military success unlikely, the groups are also so disparate that they render dialogue impossible. Members mostly do not even know the name of their group, and often the real name of superiors; further, membership is secret and the insurgents do not claim responsibility for attacks.

The degree of cohesion is fiercely debated, some seeing groups as flexible but with an order of command and commander intent being present while others doubt any coordination between groups at all. The renowned scholar and former National Reconciliation Commission secretary, Gothom Arya, deems the current insurgency to be a hybrid of bottom-up, disparate cells and a top-down hierarchy, whereby the leadership gives flexible instructions which are adapted to local structures by individual cells; the initiative for certain attacks is at the cell level though training, ideological formation and preparation for each attack is at the organisation level. Thus, there is a certain amount of coordination between groups, though they also function independently and are deeply embedded in local village structures.

Discussions regarding autonomy and other political solutions to the Patani violence will only work if they receive the backing of the insurgency. Otherwise, much time and money will be spent on creating new structures that are then still the target of intense violence. At the moment, however, the insurgents are in no position to bargain as they have no coherent political arm to their operations due to their cellular and hyper-secret organisation. Insurgents must be given the space to organise themselves politically without having to constantly fear being targeted by security personnel; only then will they be able to negotiate – primarily, this can then be a negotiation of a ceasefire so that all will lay down arms; a ceasefire would then be a good basis on which to then start negotiating political settlements.

Peace deals can only come from organised insurgents

It is not uncommon across Southeast Asia to see phases of peace and violence: in both Indonesia and the Philippines, peace dialogue has continually been faced by relapses into violence, but peace agreements have only ever been possible out of a position of strength for the insurgents who can then rally their constituents into supporting the deal. At the moment, unfortunately, the Thai government appears to be doing the exact opposite through its military strategy: it is trying to divide and conquer the insurgents rather than encouraging them to cooperate and engage politically. Further, not only within the groups themselves must this organisational cohesion progress, but also dialogue between the groups should be facilitated in order to preclude later factional violence.

It is absolutely pivotal that insurgency groups be encouraged to organise politically and come to the negotiation table as soon as possible. By involving them in dialogue on the region’s future the violence and bloodshed that has been plaguing Southern Thailand for nearly eight years now can be brought to an end for their own benefit.

Timothy Williams is a PhD student at the Free University Berlin with a research focus on genocide perpetration. He also writes a blog on violent conflict and has worked as a risk analyst on governance, human rights and conflict issues.

This article was originally published on Timothy’s blog and can read by clicking here.