Modi’s Outreach To Bhutan: Perception Management And The Neighbourhood First Policy – Analysis

By IPCS

By Ashutosh Nagda and Angshuman Choudhury*

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Bhutan in August 2019 as part of the first phase of foreign state visits after assuming office for a second term. The visit came less than three months after Bhutanese Prime Minister Dr Lotay Tshering’s visit to India for Modi’s swearing-in.

The content and language used by the India during this visit reflects New Delhi’s intent to diversify its relationship with Bhutan, and undertake perception management to dismantle its ‘big brother-hegemon’ image. The visit served well to reinforce the Modi government’s ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy, and was particularly significant with regard to China’s clout in South Asia.

Agenda Diversification

The 2019 visit builds on the 2014 one, which had reinforced India’s hydropower and grant-based outreach to Bhutan. This time, both sides signed ten MoUs, of which seven focused on education, and one each on space cooperation, disaster management, and hydropower engagement.

Modi also formally launched the flagship Indian RuPay cards for use in Bhutan and agreed upon a feasibility study on the Bharat Interface for Money (BHIM) app. India offered, as a “gift”, increased bandwidth to Bhutan on the South Asian Satellite (SAS), which has already boosted the cost-effectiveness of Bhutan Broadcasting Service and enhanced the country’s disaster management capability.

Evidently, the basket of issues on which New Delhi engages with Thimphu is being diversified, with greater focus by the former on soft power projection and technological linkages. Interestingly, this is in line with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) 2019 election manifesto, in which it promised to make “knowledge exchange and transfer of technology for the development of all countries” a prime focus of diplomatic relations.

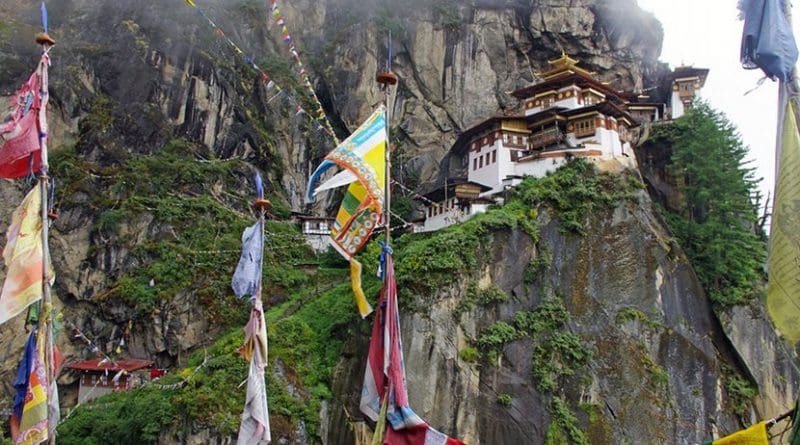

The play on cultural symbolism by Modi, too, was not lost when he addressed Royal University of Bhutan students, and offered prayers at the historic Semtokha Dzong in Thimphu, which houses an India-loaned statue of the Bhutanese state’s founder, Zhabdrung Ngawang Namgyal. India extended the loan period for this statue for another five years, and also added three more scholarship slots for Bhutanese students at Nalanda University.

This renewed diplomatic outreach by India builds on the good faith that both countries began forging after a few hiccups on issues such as India’s hydropower tariff and cross-border electricity transfer rules, which drew Thimphu’s concern. While India initially showed some inflexibility, relations later evened out. Tshering, who called the India-Bhutan relationship “non-negotiable,” being elected as Bhutanese PM in 2018 has further helped mend the rift.

India’s Perception Management Policy

The India-Bhutan relationship, although healthy on most counts, is often weighed down by negative perceptions of India as a regional hegemon within Bhutanese media and civil society. This is even more so given the unique relationship that both share as close allies by virtue of a ‘friendship treaty’.

The relationship came under serious test during the India-China military standoff at Doklam in 2017. It triggered discussions within Bhutan regarding its ‘over-dependence’ on India, and the need for Thimphu to balance its regional relationships by forging closer relations with Beijing, with whom it does not have formal diplomatic relations. China has since tried to reach out to Bhutan through increased trade, tourism, and a lucrative ‘package deal’, which Bhutan later rejected.

India’s expansion of cooperation and the language of collaboration used by Modi during this visit must be seen in this context of regional dynamics. By framing India’s developmental aid and cooperation as a function of the “the priorities and wishes of the Government [of Bhutan] and the people of the Kingdom of Bhutan,” New Delhi is attempting to shed its image of a ‘big brother’, and posture itself as an equal developmental partner that believes in building horizontal, not vertical, partnerships.

This perception management exercise is well-timed to counter China’s charm offensives in Bhutan. It becomes more crucial in light of the growing assertiveness of pro-China lobbies within the Bhutanese elite and media. Notwithstanding Thimphu’s dismissal of Chinese aid after Doklam, negative domestic perceptions about India’s role remain, and may even take centre-stage in the future.

While India’s generous and consistent developmental aid still holds high value in Bhutan, China has much to offer in terms of investments, jobs, market access, and affordable public infrastructure. This, naturally, has not gone unnoticed. In the years to come, aspirational Bhutanese youth could amplify their demand for diversified geoeconomic regional linkages for high-voltage national development, particularly in light of soaring youth unemployment.

It is in this background of unpredictable regional equations that India is fine-tuning its bilateral outreach. With China using similar developmental semantics of “extensive consultation, joint contribution, and shared benefits” under its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), India can no longer afford to look like a dominant regional entity that relies on financial largesse without addressing the specific needs of smaller regional allies.

A Sharper ‘Neighbourhood Policy’?

Modi’s language of cooperation in this visit mirrors the language used during his June 2019 Maldives visit, where he spoke about India’s cooperation being “based on the requirements and priorities of Maldives.” A similar language of need-based development was deployed in Modi’s 2015 visit to Afghanistan.

These reflect an emerging pattern of diplomatic outreach that New Delhi is increasingly relying on to retain influence in the neighbourhood. In many ways, it is reactive to China’s ‘equal partnership’ posture towards small and middle South Asian powers as propagated under BRI. Ultimately, it reflects a timely endeavour that could set a new precedent for South-South cooperation in South Asia, and maintain a regional order as envisaged by India.

*Ashutosh Nagda is a Researcher with IPCS’ South East Asia Research Programme (SEARP). Angshuman Choudhury is Coordinator, SEARP, and Senior Researcher.