The History Of The Jews Of Sefrou – Analysis

The Moroccan Jewish community has always been and remains one of the largest in the Arab world. Its heritage and history are little known abroad, although every part of the Kingdom has an important Jewish legend. Jews have been in Morocco for hundreds of years, and have lost none of their ancient traditions, customs, religion, and culture. Moroccan kings protected the Jews from harm and helped some of them develop the wealth that sustained the monarchy for many years.

Sefrou, the city of tolerance and coexistence

Sefrou is a large town in north-central Morocco that has 87 162 inhabitants according to the figure of the Haut-Commmissariat au Plan for 2023. (1) It is located at an altitude of 850 meters (2,790 feet) in the foothills of the Middle Atlas just above the Sais plain, and only 30 kilometers (18 miles) south of Fez. The city is bordered to the north by the mountains of the Rif, to the south by the Atlas Mountains, to the east by the Taza Straits and to the west by the Sais Plateau. The town is situated in a green, picturesque setting surrounded by gardens and fruit orchards.

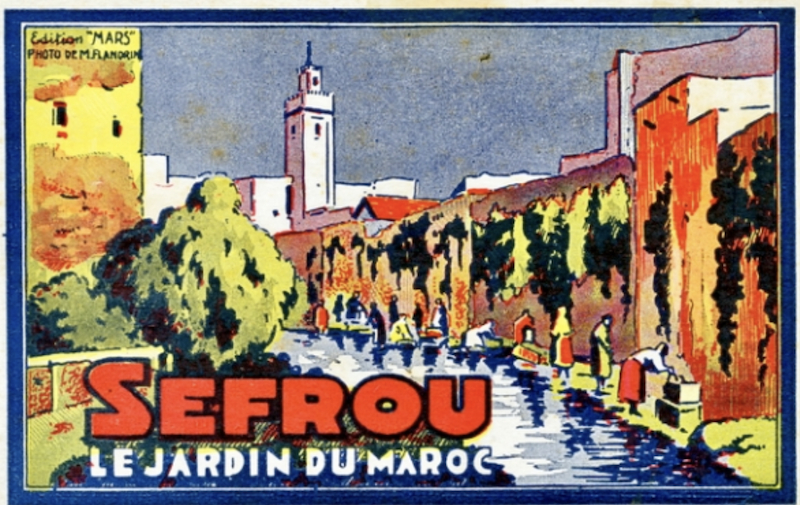

The city spreads out over a fertile plain irrigated by the Oued Aggaï (or Assif n-wAggay which means ‘’cheeks’’ in Tamazight language), a river renowned for its devastating floods. The river crosses the city of Sefrou. (2) The name Sefrou is Assefrou (ⴰⵙⴼⵔⵓ): As, is the place in Amazigh language, and Afrou is the hiding place or cave. Beyond the mellah, the river is called Oued Lihoudi “The River of the Jew”. This river supplies all the canals and allows the irrigation of the numerous gardens of the city. Sefrou is also known for its waterfall, which explains the freshness of the place, as well as the abundance and richness of the vegetation, which earned the city the nickname of Le Jardin du Maroc “Garden of Morocco”.All the names, or toponymy, in and around Sefrou; are in Tamazight language, and this was very long before the arrival of the Arabs; for example: Tighdouine, Taryala, Tagnite, Igurazen, Glat, etc.

Historically, it is the valley of the Oued Aggay, a small tributary of the Sebou, which first channelled human settlement in this region. The presence of a multitude of caves dug in the limestone and travertine, facilitated the first settlements as well as in Mazdghat Al Jorf, Bhalil, Imouzzar Kandar and Al Hajeb. According to Mbarek Bekkai, (3) this form of occupation dominated until the seventh century, when the Amazigh/Berber troglodytes began to familiarize themselves with construction techniques.

However, the need for defense, probably linked to the first Muslim incursions into the Atlas, dictated that they regroup and build fortifications. Thus, there are erected along the valley a cordon of qsûr, (4) located in three points: upstream of the Oued Aggay, in the center, and downstream of the Oued, near its confluence with Oued Sebou. But gradually, the central site coinciding with that of the current Medina of Sefrou, proved advantageous and became a pole of crystallization, and this to the detriment of the other qsûr. Consequently, an agglomeration bearing the name of Sefrou was born since, it was probably towards the end of the 7th century. However, a small residual core remained upstream. Namely the district of Qalca, whose inhabitants do not hesitate until our days to distinguish themselves from the inhabitants of Sefrou proper.

The Ahl Sefrou, who lived in the region, were once Amazigh/Berbers converted to Judaism. They were Islamized in the 8th century by Moulay Idris II (791-828). In addition, in the 13th century, the city became home to a large Jewish colony from the Tafilalet region and southern Algeria, some of whose descendants are said to still exist today. (5)

Sefrou became from the 12th century a center of trade and exchange where the producers of the northern regions of Morocco and those of Tafilalet gathered, and as such there were trade caravans between the two regions. (6)

The mellah (Jewish quarter) of Sefrou, located in the old city, south of the medina and separated from it by the Oued Aggay, contains the Zaouïa of Sidi Lahcen Ben Ahmed, a 17th century Sufi saint. From there, there is an old stone bridge which spans the wadi to reach the mosque Jâmec l-Kbir and the suq (bazaar) of the medina. The old city, made up of a maze of tortuous lanes and where the houses built on the side of rocks are tiered, is surrounded by a rampart with crenellations of the 18th and 19th centuries. (7)

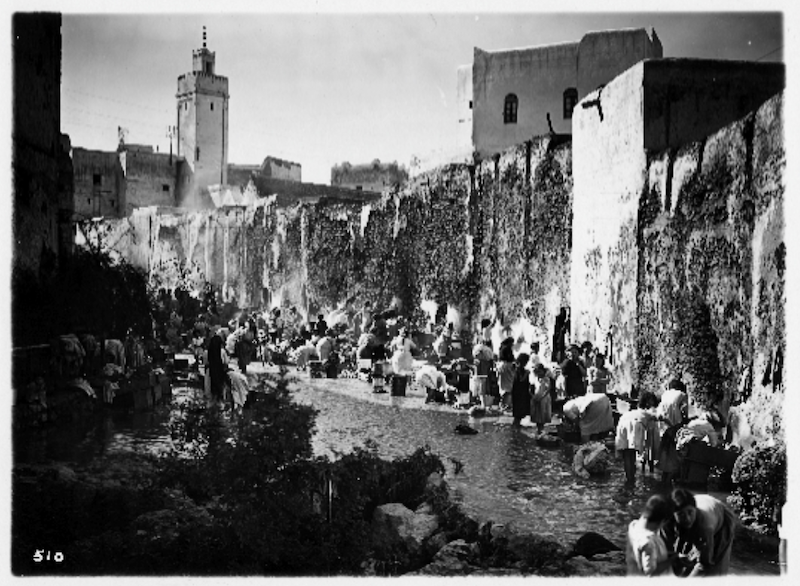

At the exit of Sefrou, the mills and the laundries border the Oued Aggay, whose cascades, located more in the North-East, were partly damaged by the flood of 1977. The city is known for its cherries, and thus it celebrates annually, with much gusto and pomp, the Cherry Festival, known in Arabic as moussem habb l-mellouk (The Season of King’s Grains), created in 1920 and protected since 2012 by UNESCO on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Prior to the massive emigration of the Jews to Israel, during the Cherry Festival, the inhabitants of the region follow the procession to the cave of Kâf al-Moumen which shelters the tomb of the prophet Daniel and where, according to a local legend, ‘’Seven Believers and their Dog’’ (8) /’’Seven Sleepers” (9) would have fallen asleep during centuries. Fantasias, dances, and songs punctuate this important agricultural event. In the west of the city, a miraculous spring, called Lalla Rkiya, which is supposed, according to a popular belief, to have the power to cure madness. The blood of sacrificed animals is poured into this spring during this moussem to give it more vibrancy and revive its curing power. (10) For local intellectuals, this is one of the many pagan rites found in Morocco and recorded by the Finnish ethnographer Edward Westermarck in his book entitled: Ritual and Belief in Morocco. (11)

Sefrou was once a major center for Morocco’s Jews and its walled white pedestrian medina is still characterized by their houses with wooden balconies. It was a good example of interfaith dialogue in Morocco, coexistence and tolerance. Indeed, in Sefrou lived Muslims and Jews in good harmony door to door and practiced their religious rituals in unison.

Sefrou is an old city, surrounded by ochre or red walls, crenelated which enclose since 1820, its picturesque districts, its suqs, its bridges, its waterfalls on the Aggai wadi which crosses the city and irrigates all the enchanting corners of this garden city, it was called ” the Garden of Morocco “.

The curiosity of the visitors was solicited by the mellah which offered a particular interest with its high three-storey houses, painted with bright colors, its balconies in painted wood and its facades pierced with small grilled windows. In these high houses, a little mysterious in the maze of narrow streets, lived a large and cheerful Jewish population, respecting ancestral traditions. Today there are no more Jews in Sefrou and a large part of the mellah is in ruins.

It is undoubtedly one of the oldest cities of the country. It would even have been built before Fez, in the year 682. The anteriority of the construction of Sefrou, compared to that of Fez, was noted by Hassan al-Wazzan al-Gharnati, known as Leo Africanus. (12) A reality that would have been underlined, from the beginning of the 14th century, by the chronicler Ali Ibn Abi Zar in his “Rawd al-Qirtâs“: “One went from the city of Sefrou to the village of Fez“, he could write. (13) The city will be described, at the beginning of the 20th century, as “one of the most prosperous and orderly of Morocco“.

It was in 807, when the construction of Fez had just been launched, that Idris II, the native of Volubilis would have come to settle for more than two years in a village on the banks of the Aggay river, which he would have named “Habouna“, “those who loved us”, and which is today one of the districts of the city.

Sefrou is also famous, since centuries, for the harmonious cohabitation of the three Abrahamic religions, of which it was the haven as the following verses of the venerable Sufi Sheikh Abdelkader Tomouri testify: (14)

“O you visitor, have you been informed of the beauty of this city?

Its gardens, its waterfalls and its sites,

Which give you the joy of the eyes and the happiness of living.

Its climate, its water and its cherries are for you the remedy to all the evils.’’

Whether you are Jewish, Christian or Muslim, the people of this city welcome you with open arms. And at dawn, they will, customarily, take you to the highest point of the hill to recover the baraka (divine grace) of the venerated patron Saint Sidi Ali Bousserghine. (15)

In the 19th century, in fact, in Sefrou, the Jews were more numerous than the Arabs and the Amazighs and the city was a haven of peace and conviviality (16) where Muslims and Jews lived in total communion. (17) The mellah would have been built as early as the 13th century, under the reign of the Marinid Sultan Yaqoub ben Abdelhaq (1215–1217). The city’s Jews were mostly artisans specializing in copper, silver, gold, and leather, but also practiced weaving, carpentry, and the wood and coal trade and were also small bankers and caravan guides.

The old medina is surrounded by crenelated ramparts, has 7 gates, many borjs (towers), Jewish houses with their balconies, zaouias (religious lodges), mosques, bridges and funduks (caravenserais).

After the foundation of Fez in the 9th century, Moulay Idris II succeeded in converting the inhabitants of the city. The city gained in importance in the 12th century thanks to its location between Fez and Tafilalet, developed further a century later when it received an important Jewish colony from Tafilalet and southern Algeria.

The city visited by Maurice de Perigny in 1916 is described in the following terms: (18)

[‘’The Oued el Youdi, after having crossed the city, passes at the foot of a beautiful mosque under a very old bridge and rushes in a series of cascades at the bottom of a gorge all covered with a thick grass and green plants, dotted with clumps of trees. The natives have skilfully harnessed its waters with various small canals operating several mills arranged in stages. This is about the only industry that exists in Sefrou. There are about ten of these wheat mills, while a dozen oil mills are scattered throughout the city.’’]

‘’The Oued el Youdi, after having crossed the city, passes at the foot of a beautiful mosque under a very old bridge and rushes in a series of cascades at the bottom of a gorge all covered with a thick grass and green plants, dotted with clumps of trees. The natives have skilfully harnessed its waters with various small canals operating several mills arranged in stages. This is about the only industry that exists in Sefrou. There are about ten of these wheat mills, while a dozen oil mills are scattered throughout the city.’’

The city of Sefrou is the city of saints and sainthood, it counts the marabouts of Sidi Boumadian, Sidi Lahcen, sidi Ahmed Tadli, Lalla Rkia and Sidi Bouserghine. The zaouias are about fifty in number, including the Zaouia Sadikia in Qalca , a former district of the Boukharas (19) (old army of foreign fighters of the Alaouite Sultan Mouly Ismail (1645-1727)), it is situated on the right bank of the Aggay river, on a hill giving a panoramic view of the city. Not to forget of course the numerous Jewish scholar saints of the city that earned it the title of Little Jerusalem of Morocco.

The Jewish population of Sefrou

In the time before the arrival of Moulay Idris II, many Jews driven out of Algeria by the Arab conquest took refuge on the banks of the Aggaï wadi. Thanks to the rich gifts that they offered to the qsûr (early inhabitants of Sefrou), the latter welcomed and protected them.

The tranquillity that the Jews enjoyed in Sefrou was well known, so many of their co-religionists from Debdou, Tafilalet and even southern Algeria came to join them. Numerous and sufficiently rich, they bought from the Sultan reigning at that time the site where the current mellah was built which replaced the “Ksar al-Koufâr” (village of the miscreants). The location of this old mellah is at the bottom of the waterfall located downstream from the city.

The mellah was built there during the reign of the Marinid sultan Yaoqub ben Abdelhaq. The Jews of Sefrou were craftsmen specialized in copper and leather, but they also practiced weaving, carpentry, wood and coal trading. (20)

In 1890, the flooding of the river caused the death of many of its inhabitants, including several members of the Jewish community; the same disaster was repeated in 1950 and further reduced the community, which then numbered 5,000 people. (21)

The fame of the rabbis of Sefrou, such as Rabbi Moshe Elbaz, known as the ‘’Master of the Cave’’, extends beyond the city, throughout Tafilalet and outside Morocco. The city is also a resort for the townspeople of Fez and Meknes, and a place of Jewish pilgrimage to a saint buried near the Jewish cemetery. The city is known worldwide for its scholarship in Talmudic studies and religious knowledge.

The mellah of Sefrou included seven synagogues of various sizes. Only one family synagogue, founded towards the end of the 18th century, remains, but in a state of ruin. It testifies, however, to the architectural layout and ornamentation of the synagogues of this city.

It is also worth noting the presence of a school belonging to the Alliance Israélite Universelle, created by this very organization in the 19th century, and which remains in a good state of preservation. It presents the typical plan of a Moroccan synagogue. The prayer hall is divided into three naves parallel to the Haykhal by two rows of arcatures surmounted by columns topped with tree-trunk capitals. This synagogue also has a Thiba and a room on the floor reserved for women.

Walking through the city, one imagines the melodies of Hebrew songs coming through the windows of the synagogue. It was warm, it was vibrant, it was cheerful, it was the Jewish community of Sefrou that prayed, sang, and wished each other well in this synagogue. (22)

The Jewish population of Sefrou has declined from a peak of 33% to 44% in the 1930s-40s, the cemetery is being restored by the small remaining community and with contributions from expatriates. Headstones have been mounted inside cement monuments, many of which honor the memory of a group of merchants who died in a truck accident, while others commemorate the victims of the 1950 flood.

The cemetery features a number of “saints,” including: Moshe Elbaz, ‘’the Master of the Cave’’, Eliahu Harraoch, David Arazil, Rabbi Rapyhael Moshe Elbaz, Rabbi Abba Elbaz, Rabbi Ismah Ovadia, Rabbi Raphael Maman, and Rabbi Zeev khalfon .

Jewish burial in the cemetery is normally on the day of death. The deceased is be buried as soon as possible. There are no Jewish funerals at the synagogue. The coffin does not pass through the synagogue, which is considered a place of life. The cemetery is, however, the place for the religious ceremony, the prayer is made by the rabbi who says the prayer of the dead, a hymn of praise to God (23) (Kaddish קדיש).

Everyone participates in the burial by placing a stone on the coffin or grave. No flowers are sent. Before leaving the cemetery, one washes one’s hands, without wiping them, because one has contracted an impurity. Then everyone meets at the house of the deceased to eat bread and boiled eggs.

Jbel Binna and its caves

The archaeological site of Binna was the subject of an important discovery. Thus in 1965, the two caves of Kâf al-Moumen and Kâf al-Bagra which pierce this rocky outcrop would have revealed the existence of a prehistoric industry of tools in flint and basalt. Paleontological remains such as teeth of bears, rhinoceros, and other extinct species. Cave paintings have unfortunately completely disappeared and can only be seen in photography.

The natural cavity located on the side of Jbel Binna is at the entrance of the city of Sefrou. The cave of the believer, Kâf al-Moumen, keeps in its heart many legends. It is venerated by Jews and Muslims. (24) This cave is a good example of shared spirituality. (25) Today, it is completely abandoned because the Jews of Sefrou all left for Israel after the 1967 Six-Day War and most Muslims despise the idea of worshipping a cave on their own and consider it a pure expression of shirk resulting from popular beliefs rooted in pre-Islamic practices. (26) This appears, however, as an extreme reaction to the departure of the Jews who were their co-worshippers of this unknown saint. Today, Islamists to mock this shared saint argue forcefully that it is the graveyard of a mule that faithfully served his owner, so upon its death, he built a shrine for it and circulated the story that it was a saint. For others, it is an illustration of the naturalistic cults that still exist in Moroccan beliefs among Muslims and Jews and that have been studied in detail both by Doutté (27) and by Westermarck (28) during the last century.

Every year, this cave was the object of a real naturalist cult on the part of the Jews of Sefrou and Fez. The pilgrimage of this cave took place at the same time as the one of the sanctuary of the great Rabbi Hamou ben Diouane, in Ouezzane.(29)

As for the existence of Christians in the country, Arab texts also suggest it. Moreover, from the seventh to the ninth century, pagans, Jews, and Christians are often mentioned in the chronicles that report on the military campaigns carried out in Bhalil by the Chkounda family, probably descendants of the Second Roman Legion, and the discovery in al-Anaser, south of Sefrou, of the fountain of idols (Ain Sname) from which five Latin inscriptions were exhumed, attest if not to a Roman settlement, at least to an interest by Volubilis in the southern front. In this case, were not al-Anaser, Bhalil, and Mimmet (now disappeared) watchtowers erected by Romans to face the Atlas Mountains with a military aim? For the moment, no argument allows to affirm this, and only thorough excavations would allow detecting traces of it. It is, thus, in a very coveted site that Sefrou was born.

Leo the Africanus says that Sefrou was founded by the Africans, that is to say the Amazigh/Berbers. If one believes the public rumors, the city would have been built before Fez. “One was going from the city of Sefrou or the village of Fez“, the Sefrioui inhabitants have been repeating for a long time. According to the local legend, abusively attributed to Rawd al-Qirtas, Idris II, at the time when he had launched the construction of Fez, would have come to settle for two years in this city of piedmont (807). He resided in the dshar (quarter) known as “Habouna”, the village of “those who loved us”, a name that Idris II would have given to this place, which is now located south of the Medina, as a sign of gratitude for the warm welcome he had received from the inhabitants of the city during his campaign of Islamization. The Bahloula (people of the village of Bhalil), being more reluctant, would not have received his blessing.

In any case, Sefrou seems to have existed at the time of the foundation by Idris II of the city of al-cAliya (the city of Ali) on the left bank of the Oued Fès, in 809, on the site of the Qairaouan quarter which faces the Andalusian quarter, built by Idris I in 789. The fact that during the reign of Ali Ibn Idris, grandson of Idris II (836-848), a political opponent seized Sefrou, and marched on Fez, proves that around the 9th century, the city was already strong enough to mobilize against an Idrisid sultan.

The Jews of Sefrou

The city began as a market town in the Roman era and as a stopping point for caravans of traders making their way from the Mediterranean to the Sahara Desert, then became a major Moroccan town long before Fez was built in the 8th century.

Sefrou was once home to one of the largest settlements of Moroccan Jews, with an estimated population of 8,000. The first Jews lived in the Ahl Sefrou region, most of them having been converted to Judaism about 2,000 years ago. In the 8th century, most of them were converted to Islam under Idris I (743-791). In the 9th century, a second Jewish population wave from the Tafilalt region and southern Algeria settled in the city. Most of the descendants of these Jews remained in Sefrou until 1967, when they made their Aliyah to Israel.

However, in the 19th century in Sefrou, Jews outnumbered Arabs and Berbers. Peaceful and welcoming, this city dazzled travellers through the ages to the point that Colette spoke of it in 1926 as a “Le paradis terrestre/The earthly paradise“: (30)

[‘’Sefrou: The earthly paradise, more or less as we imagine it, if we imagine it oriental and populated, and restricted. Sefrou is a puddle of fertile, juicy earth, all quivering with the laughter of water. The pomegranate tree blazes, the cherry swells, the fig tree smells of milk, the grass delivers its juice as soon as you crush it. The rose of Bengal masters the vine, a playful wind whitens the pens showing the backside of all the leaves at once. Such a sweet place makes the man amiable: the boys are beautiful, the smooth young Jewish girls sparkling with eyes and teeth, and the water leaps under the bridges between rocks and wheat terraces where the grain, shoveled by children, flows like a blond shore.”]

”Sefrou : Le paradis terrestre, à peu près tel que nous l’imaginons, si nous l’imaginons oriental et peuplé, et restreint. Sefrou est une flaque de terre fertile, juteuse, toute frémissante du rire de l’eau. La grenaderaie flambe, la cerise enfle, le figuier sent le lait, l’herbe livre son suc dès qu’on la froisse. La rose du Bengale maîtrise la vigne, un vent joueur blanchit les enclos en montrant l’envers à la fois de toutes les feuilles. Un lieu si doux fait l’homme aimable : les garçons sont beaux, les jeunes juives lisses étincelantes d’yeux et de dents, et l’eau bondit sous les ponts entre des rochers et des terrasses à blé où le grain, pelleté par des enfants, coule comme une grève blonde.”

The Jews who resided in this city were Amazigh/Berber-speaking natives from Tafilalet, Arabic-speaking Fassis (from Fez) as well as descendants of the Spanish exiles of 1492 known as megorashim.

Very much a part of their city, the Jews were masters of their own situation and prospered as small craftsmen, merchants, bankers, caravan guides, rabbis, or Hebrew teachers. One of the most eminent members of the community was the Rabbi and judge Shaoul Yéhoshouah Abitbol (1740-1809), known, among other things, for his collection of legal decisions Avné chèch (Blocks of Marble).

With the arrival of the French, the decadence of the city of Sefrou went hand in hand with the economic crisis that hit Morocco. The Alliance Universelle opened French-speaking schools and disrupted the educational model of the Hedarim (traditional Jewish elementary schools around the teachings of the Torah). In the early 1980s, Norman Stillman reported that there were only four old people of Jewish origin left in the mellah of Sefrou.

Just south of Bab Merbac, there is former Jewish school with its own synagogue that is now closed, but one can still peak through the doors – it’s pretty rundown, however.

On the right bank of the Aggay river, and in the heart of the old Medina of Sefrou is the residential district of the Jews near the great mosque Jamac Lakbir and near the commercial center of the other bank of Oued Aggay.

Sefrou is also known as the Little Jerusalem of Morocco which is a bastion of the country’s diverse heritage. It’s old mellah, or Jewish quarter still stands in Sefrou’s medina. It is distinguished by its low walls and reached by crossing a short bridge over Oued Aggay, which passes through the old medina. Today, this part of the city is mostly inhabited by Muslims.

In addition to their commercial role, the Sefrioui Jews provided communication services in the whole region of Sefrou which extends from the city of fez in the north to the region of Tafilalt in the south. The Jewish population accounted for almost half of the sefriouis before the French colonization, but after independence, they started leaving for Israel. The district remains without maintenance, degrading and sheltering among others the prostitutes and the outlaws.

While there were no more than 5,000 Jews in Sefrou in 1948, they lived mostly in the mellah. The population density of the Jewish community at that time was 415,815 per square kilometer, the highest in the country. To cope with the high population density, most buildings have three stories, with balconies facing the street. In 1960, the 3,000 Jews constituted 15% of the population. However, with the arrival of the French in 1912 (French Protectorate 1912-1956), rich Jews moved to live in the European quarter known as Ville nouvelle as well as Jews that worked for the French administration as civil servants mainly as interpreters or translators for those who were learned in Arabic language.

In the heart of the city, there is the famous “Jewish washhouse” where every morning a good number of Jewish women come to wash their copper basins and to beat the linen, in the clear, fresh and fast waters of the Aggay river (which will take the name of Oued Lihoudi – River of the Jew – after its passage to the Mellah), forming a unique and picturesque picture which has often seduced the artists.

Sefrou is, also, home to the oldest school of Rabbis in Morocco as well as other Jewish sanctuaries and synagogues.

As soon as Mohammed V ascended the throne, the Jews felt that a radical change would take place between the Jews of Sefrou and all of Morocco and their ruler. The new sultan, who ascended the throne in 1927, was exactly the opposite of what the French expected. They wanted a docile sultan; they found in him a nationalist who gradually established himself as the leader of the struggle for independence, and as far as the Jews were concerned, he systematically obstructed the anti-Semitic measures that the Vichy government wanted to impose on the Jews of Morocco. With each new Vichy law, the sovereign took a fierce defence of the Jews, even to the point of confrontation with the Resident General, taking care to recall each time that Jews and Muslims were equally his subjects and that he would not suffer any discrimination between his children. (32)

The Jews of Sefrou, like all the Jews of Morocco, expressed great veneration for Sultan Mohammed V during the period of the French protectorate for having always protected his Jewish subjects. In fact, Sultan Mohammed V, during the Feast of the Throne in 1944, addressing his Jewish subjects said: (33)

”Just like Muslims, you are my subjects and as such, I protect and love you, believe that you will always find in me the help you need. The Muslims are and have always been your brothers and friends.”

On his deathbed, Mohammed V is said to have made his son (the future Hassan II) promise to watch over the “salvation of the Jewish community“.

On the day of the death of the sovereign, the Jews of Sefrou felt great sorrow and went out into the street to mourn him, and to share the grief of their Muslim brothers.

Rabbi and judge Shaoul Yéhoshouah Abitbol (1740-1809)

Son of Rabbi Yitzhak, he is the founder of the dynasty of rabbis who distinguished themselves for two centuries in Sefrou. (34) Nicknamed, according to the Hebrew initials of his name, Rav shisha. He was appointed Dayan judge at the age of 18, and he presided over the rabbinical court for half a century.

His reputation in Halakha הֲלָכָה went far beyond the borders of his city, reaching the whole of Morocco. By witnessing the elegies composed at his death by the two great Jewish poets of Meknes, Rabbi David Hassine (35) and Rabbi Yaacob Berdugo.

His legal decisions set precedents before the rabbinical courts of Morocco, although they were printed only very late – with his sermons and commentaries – in Jerusalem in two volumes in 1930 and 1934, under the title of “Avne Shaish”. (36) His son Raphael was also a well-known Rabbi in Sefrou.

50 – אל משוש אר”ש יפה נוף

פיוט יסדתי לכבוד החכם השלם דיין מצויין כבוד הרב ישועה שאול במתא צפרו יע”א

אֶל מְשׂוֹשׂ אֶרֶ”שׁ יפה נוף / לכבודו זמר שיר אביעה

במצנפת בַ”ד צָנוֹף יִצְנֹף / ובראשו כובע ישועה

כאן הכינויים של כבוד רבי ישועה

משור אר”ש – משחק לשון שכיח, המילה אר”ש מציינת יכולת הבעב ולמדנות

במצנפת…יצנוף : ציין ב”ד בגרשיים לציון ראשי תיבות בית דין, ששירב רבי ישוה כחבר בו

נאספו בו כל ההדרים / פקודי ה’ ישרים

מפי סופרים גם ספרים / מרכבותיך ישועה

מפי סופרים וספרים…שלמד גם ממוריו וגם מן הספרים

יום זה נכבד ראו עיני / גבעת שאול בחיר ה’

אשר בשירי ורנָנָי / זמרת יה ויהי לי לישועה

גבעת שאול בחירו : ציין בזה את מקום מושבו של רבי שאול ישועה, העיר צפרו

דור ישרים בואו שעריו / מצוף דבש מָתקו אֲמָרָיו

יראת ה’ אוצריו / רחוק מרשעים ישועה

ואותו יום תדרשוּן / אשר יאמר לכם תעשון

ושאבתים מים בששון / ממעיני הישועה

דָן ידין עמו בְּיֹשֶר / ומטיב דרך מְיַסֵּר

משיע שלום מבשר / טוב משמיע ישועה

ומטים דרך : הסרים מדרך הישר ומדרך התורה

מיסר : הוא מעניש ומוכיח

חסין קדוש ירבה שלומו / ישים את המִשְׂרה על שכמו

יִרצה ה’ בעמו / יפאר ענוים בישועה

- לחצו כדי לשתף בטוויטר (נפתח בחלון חדש)

- לחיצה לשיתוף בפייסבוק (נפתח בחלון חדש)

- יש ללחוץ כדי לשלוח קישור לחברים באימייל (נפתח בחלון חדש)

The elegy composed by Rabbi David Ben Aharon Hassine (The Poet of Meknes) in Hebrew

Rabbi Raphael Moshe El Baz (1823-1896)

In the image of a plural Morocco with its cities where Muslims, Jews, and Christians lived side by side, is exemplified in the city of Sefrou which has for centuries welcomed a community of Moroccans of the Jewish faith. This is notably the case of the El Baz family. (37) With a name of Arabic origin meaning “the hawk”, El Baz was a family of scholars, judges and rabbis. These include Maimon El Baz, rabbi in the seventeenth century, author of a cabalistic commentary on prayer rituals, Shmuel El Baz rabbi in the seventeenth century, member of the Rabbinical Court and author of Talmudic commentaries or Amram El Baz, a rabbi-judge and codifier who lived in the eighteenth century.

Born in Sefrou, Morocco, in 1823, and died in the same city in 1896. He was the son of Rabbi Samuel who was the son of Rabbi Yehuda. He symbolized the last incarnation of the perfect scholar of the Spanish tradition, harmoniously mixing sacred studies with the so-called profane sciences, whereas since their installation in Morocco, the descendants of the expelled from Spain, the megorashim, did not show any interest in sciences and philosophy. He was the revered guide of his community and his reputation went far beyond the borders of his city. (38)

It is within this family, which is of Spanish origin according to some sources, that Rabbi Raphael Moshe El Baz was born in 1823 in Sefrou. He was the son and grandson of two prolific rabbis and authors: Rabbi Yehuda El Baz and Rabbi Samuel El Baz.

Precocious, Rabbi Raphael Moshe El Baz was appointed rabbinical judge at the age of only 28. And at the time, he was already a “prolific writer”, dealing in his books with various fields, such as the writings of rabbinic jurisprudence, precepts, laws, and commandments that govern the life of the individual according to the law of Moses.

He symbolized the last incarnation of the perfect scholar of the Spanish tradition, harmoniously blending sacred studies with the so-called secular sciences, whereas since their settlement in Morocco, the descendants of the expelled from Spain no longer showed any interest in science and philosophy.

Talmudist, Kabbalist, grammarian, poet, singer, philosopher, astronomer, historian, paytan, (39) and mathematician, he entered the rabbinical court at the age of 28 and was, until his death at a very advanced age, the revered guide of his community. His reputation went far beyond the borders of his city.

Over the years he cultivated a reputation as a great scholar and religious authority. Indeed, one year when the drought threatened to bring famine to Morocco, Rabbi Raphael Moshe El Baz organized according to custom a great prayer at the cemetery with all the men of the community. On their way back to the mellah, heavy rain began to fall and he was received like an angel from heaven by the Muslim peasants. The Pasha (mayor) of Sefrou ordered the farmers to give a share of their harvest to the rabbi that year, because they owed it to him.

The rabbi maintained excellent relations with his Muslim compatriots, not hesitating to go to the mosque to listen to Muslim liturgical music or to echo, from his window, the call of the muezzin to prayer, reciting bakkachot (Baqashot) שירת הבקשות (sung prayers) (40) in their translation into Arabic.

For, in addition to being a rabbi and a judge, Rabbi Raphael Moshe El Baz was also a lover of songs and poetry. He composed several didactic songs and poems in dialectal Arabic, in addition to many poems that have become part of the liturgy.

Along with Nissim El Baz, Rabbi Raphael Moshe El Baz is also considered one of the Jewish poets who adopted the popular Arabic, semi-classical genre called qasîda. (41) He is even described as one of the most representative artists of Hebrew poetry in Morocco. (42)

During his 73 years, Rabbi Raphael Moshe El Baz also wrote several books, including “Halakhah Le-Moshe” which is a collection of legal rulings, “Parashat Ha-kessef” which is a work of morals and proverbs, “Arbah’a Chomrim” on jurisprudence, “Chir Hadach” where he collected liturgical songs and poems or his famous “Beer Cheva” on the sciences; in this case mathematics, astronomy, and geography, as well as a book on the Moroccan Jewish community, entitled “Kissé Hamélakhim“.

To illustrate the Rabbi’s investment in sixteenth-century texts, Sina Rauschenbach and Jonathan Schorsch (43) recall that Rabbi Raphael Moshe El Baz wrote a commentary on the sixteenth-century law code “Sefer ha-Taqqanot” (The Book of Ordinances) written by Rafael Berdugo (1747-1821) of Meknes. (44)

Having left no heirs behind, Rabbi Raphaël Moshe El Baz bequeathed no less than 19 manuscripts, which he considered “his children”, to his nephew Rabbi Benyamine El Baz. But some of these manuscripts will only be printed around the 19th century.

He is the author of Halakha le-Moché responsa, 1901 (The Law of Moses), legal consultations; Tsione Ba-Michepat (Zion in Justice); Zivhe Tzedek (Sacrifices of Justice), on the rules of the slaughter of animals; Shekel ha-kodech (Holy Shiur); Beer Sheva, on the seven sciences; Poter Mayim; Perachat ha-Kessef (Chapter of Money), a work of morals and proverbs; Holat Ahavah (Evil Love); Arba Chomerim (The Four Guardians), a work of jurisprudence; Sefera Keritut (The Book of Divorces); Kissa ha-Melakhim (The Throne of Kings), a history of the Jewish people, Jerusalem 1985; Chir Hadache, collection of poems, Jerusalem 1930 (New Songs), liturgical songs; Ateret Paz (The Crown of Pure Gold); Eden Mi-kedem, Kabbalah, Fes 1941 (The Garden from Before the Origin); Hatzer ha-mishkan (The Temple Courtyard); Turbatz he-Hazer (The Courtyard of the Courtyard).

He composed several songs and didactic poems in Arabic dialect. In addition to many poems entered in the liturgy. He left a prodigious work of which only a few volumes have been printed. His book of legal advice and responsa, Halacha the Moche, which could not be printed, was copied by hand for generations and was first printed in 1911 in Jerusalem. His collection of poems Shir Hadash was also printed in Jerusalem in 1935. His book on the history of Israel and mankind from creation to his time, written to demonstrate the inevitability of Israel’s final redemption, Kisse Melachim, was first printed in 1988 in Jerusalem by the former Chief Rabbi of Sefrou, Rabbi David Obadia as part of his series of books on the Sefrou community. His collection of seedlings Eden mikedem, first printed in Fez in 1930, was republished in Jerusalem in 1993, as well as his scientific work, unique in the literary production of Moroccan rabbis, Beer Sheva, ‘’the seven wells’’, on the seven branches of science, grammar, astronomy, mathematics, etc. This book was edited by the Rabbis of Sefrou, and was published in Jerusalem.

The recent publication of some of his works in Israel has aroused great interest in the work of R. Raphael Moshe Elbaz. The work Kissé hamelakhim (The Throne of Kings) is a universal history book, from biblical times to the time of Rabbi Raphael Moshe Elbaz. It is one of the few works that integrates the European, Ottoman and North African dynasties into one compendium. It includes important information on the condition of the Jews of Morocco throughout history.

Rabbi Raphaël Moshe El Baz died in 1896 in Sefrou, his hometown, where he was buried in the city’s Jewish cemetery. His hillula הילולא is celebrated during Lag Ba’omer, the Jewish holiday of rabbinic institution.

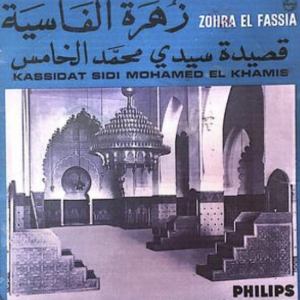

Zohra al-Fassiya, the icon of the melhoun music (1905-1994)

Morocco’s cultural eclecticism translates into a multiplicity of musical influences that have given rise to musical genres that now occupy a place of their own in the country’s rich musical culture. (45)

Judeo-Moroccan music is very strongly influenced by the legacy of the Moors. This style of music was born in Morocco after the expulsion of Muslims and Jews from southern Spain. Jewish artists did not only contribute to popular culture in terms of musical interpretation, over the centuries these musicians have composed many songs in the Arabic dialect, (46) known as melhoun. (47)

Known by her pseudonym Zohra al-Fassiya (born in 1905 in Sefrou and died in 1994 in Ashkelon in Israel), she was one of the emblematic figures and pioneers of melhoun, an authentic Moroccan musical genre.

Her father, Eliyahu, was a butcher who also sang as a Hazzan in the neighborhood synagogue. This is perhaps where al-Fassiya began to exercise her own voice by learning the piyyutim and, by extension, the North African repertoires on which their melodies were based. The young al-Fassiya probably attended the primary school of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, the French Jewish education system which, at the beginning of the 20th century, spread throughout the Maghreb for the express purpose of Europeanizing its Jewish residents.

She began her artistic career singing Moroccan melhoun in the 1920s. In the 60’s she lived in Casablanca, precisely on Sarah Bernard street, where many witnesses could hear Zohra al-Fassiya’s voice in the whole neighborhood. (48)

After her great success, she left her native country of Morocco to settle in Ashkelon in Israel until her death in 1994. Marc Tobaly, a French guitarist (born in Fez in 1950) is her grandson. In 2009, a tribute was paid to her by many artists during the festival “Warchane Slam l’Malhoun”!

She is considered as one of the icons of the grenadine song and Sh’gouri, especially since she entered the artistic field at a time when Moroccan women did not dare to go out without veils in the street, and even less to make live concerts, to make her voice heard and to spread her art in front of the public. She therefore tried to hide her family’s real name in order to preserve her “reputation”, especially since art and music were frowned upon by society. (49)

She is one of the oldest Jewish Moroccan voices to have recorded her first works in the 20’s of the last century, with the big names of the time, such as Pathé and Gramophone, when the access of women to the world of art was considered, by society, to be an infamy. It is probably for this reason that Zohra al-Fassiya was not known by her real name. She settled for the nickname “al-Fassiya”, in reference to Fez where she spent a large part of her life and from where her artistic career started, not far from the city of Sefrou where she was born in a Jewish family in love with art and singing. (50)

Zohra al-Fassiya became known for her mastery of melhoun in addition to sh’gouri, ghranati, and tlemsani, as well as some of the popular songs that Moroccans used to hum. She became famous for her song “Hbibi Diyali Fin Howa” (Where is my darling?) which many voices have taken up after her, both in Morocco and in other Maghreb countries. Salim Hilali, an Algerian Jewish artist, and lover of Morocco, was the most famous singer who sung this song in his own way. (51)

A few centuries ago, poems were sung only by men. Sometimes tinged with eroticism, they also had a social anchor. Zohra El Fassiya was the first woman to sing the famous song “Hak a Mama”. She sung at the court of King Mohammed V. She was the first Moroccan woman to write and compose songs and then sing them in public (and not just in a private setting); the first Moroccan woman also to record discs for major record labels such as Columbia Records and Gramophone Company.

Her contribution to modern Moroccan music, and more particularly to the genre of melhoun (songs composed of long stanzas in dialectal Arabic) is widely recognized. Her repertoire also includes many other genres such as shacbi, gharnati, all musical styles related to the Arab-Andalusian music of Morocco and Algeria, as well as popular songs of a more European character. (52) She emigrated in 1962 to Israel, where her talents were buried in complete oblivion. (53)

Rabbi David Obadia

David Obadia was born on 25 Yiar 5673 (May 3, 1913) in the shade of the cherry blossoms of Sefrou, son of Chimone Hayim (Yeah), president of the Rabbinical Court, author of the famous books Yismah Levav and Torat Hayim. Rabbi David was 29 years old when he was appointed rabbi of his community, thus becoming the youngest Dayane in Morocco. The chief rabbis of Fez, Meknes and other Moroccan cities had come for the occasion, as well as the members of the Sherifian Authority.

His intense activity in Sefrou revolutionized the life of this small community which will become a true spiritual center for the whole of Morocco. Very quickly he is recognized for his erudition, for his expertise in halakha, in biblical and Talmudic exegesis; for his incomparable mastery of the classical, and Arabic language; for his engaging preaching and sacred study which he brought back to the synagogue many believers who had drifted away.

Under his leadership, dynamism and charismatic personality, a new spiritual era began for the city where new ritual baths and many other religious services were built. He also founded a network of community institutions including the famous Bet David and a school for young girls, the first of its kind in Morocco. His fame spread beyond the borders and all Moroccan communities wanted him as their rabbi. In 1942, the Chief Rabbinate asked him to take over the presidency of the Rabbinical Court of Rabat, and the chief of staff of the Minister of Justice asked him to sit in Casablanca as president of the Rabbinical Court of that city. But fearing the dissolution of the network of institutions he had established in such a short time in Sefrou, he rejected all offers. In 1961, he was appointed to head the civil court of the large city of Fez, and later to head the rabbinical court of Marrakech.

His notoriety spread throughout Morocco and reached the ears of the authorities, who invited him to sit as a member of the First Consultative Assembly of independent Morocco, then, as a deputy in the Moroccan Parliament, as a representative of the Jews of Morocco to the Government of the Sherifian Kingdom.

In 1964, for reasons related to his high standards in religious matters, Rabbi David decided to move to Israel. The first years in Jerusalem were difficult: destitution and isolation. His immense humility prevented him from seeking any help or appointment. Nevertheless, he was appointed Vice-president of the Religious Council of Jerusalem.

He has published several works including A History of Sefrou in five volumes, and A history of the community of Fez and its rabbis in two volumes and he edited the Kissé Mélakhim of Rabbi Raphaël Elbaz.

He made his Aliyah in the 1960s and published in 1980 Fas vehachémeha (Fez and its rabbis). He was a member of the Rabbinical Court of Jerusalem. He opened a Yeshiva for students from Morocco.

On the death he King Mohammed V on February 26, 1962, great protector of the Jews during the Nazi Vichy government (1940-1944) in France, Chief Rabbi David Obadia pronounced this eulogy in Sefrou before the faithful gathered in the great synagogue of the mellah: (54)

[‘’Lord, our God and the God of our Fathers, in this hour of the office of Minha, accept the offering of our lips, you, Rock of the Universe! In your compassion, you who forgive and console, accept with the soul of our king Mohammed the Fifth. You, O Lord, take pity on him, forgive him, take him under your wings, place him in the midst of the pure souls of the righteous of the Nations, under the portals of Your mercy. May he rest in peace. May it be so. Amen to that!’’]

‘’Éternel, notre Dieu et celui de nos Pères, en cette heure de l’office de Minha, accepte l’offrande de noslèvres, Toi, Rocher de l’Univers ! Dans ta compassion, Toi qui pardonne et console, accueille avec faveur l’âme de notre roi Mohammed le Cinquième. Toi, ô Seigneur, prends-le en pitié, pardonne-lui, prends-le sous Tes ailes, place-le au milieu des âmes pures des Justes des Nations, sous les portails de Ta miséricorde. Qu’il repose en paix. Qu’il en soit ainsi. Amen !’’

David Assouline (1959-)

Born in Sefrou, Morocco, on June 16, 1959, David Assouline is a French politician and father of three children. A member of the Socialist Party. David Assouline began his career as a history-geography teacher at the Paul-Valéry high school in Paris. Holder of the CAPES, David Assouline has been involved in militant activities since his youth. When he entered the Jules Uhry high school in Creil, he became the head of the high school coordination against the high school reform within the Mouvement des Jeunes Communistes de France.

The Jews of Sefrou are known for their trade. But David Assouline, chose another path: history and militancy in the ranks of the far left student movements.

He continued to express his demands for social justice, notably by taking part in trade unionism and in the fight against the rise of the extreme right. He was one of the many participants in the ‘March of the Beurs’ in 1983. Three years later, he became one of the emblems of the movement against the Devaquet bill, which provided for the establishment of a selection at the entrance of universities.

The following year, in 1987, he joined the national office of the National Union of Students of France – Independent and Democratic (UNEF -ID) and joined the Revolutionary Communist League. During the presidential elections of 1988, David Assouline joined the campaign of Pierre Juquin, dissident communist candidate. In 1995, he turned to the Socialist Party.

Even if he evolves in the teaching world, David Assouline does not give up his militant convictions, in particular by following the movements ‘’Faut pas décoder’’ against the reform of the nationality code in 1993, and ‘’Stop La Violence’’’in 1999.

In 1995, he joined the Socialist Party and became director of the campaign of the socialist lists “Paris s’éveille en 1995“. He was then elected to the city council of the 20th arrondissement and contributed to the establishment of direct democracy and participatory democracy bodies, the neighborhood councils. In 2001, he was elected to the Paris council and became deputy mayor of Paris in charge of student life. He resigned from this position in September 2004 when he was elected to the Senate, but remained a Paris councillor.

In 2004, he was elected to the Senate, while being a Councillor of Paris. At the same time, he is one of the instigators of the New Socialist Party, which supported the candidacy of Ségolène Royal in 2007. In 2011, he supported Martine Aubry during the socialist primaries. David Assouline became the spokesman of the PS in 2012, until he left this position in April 2014.

A historian specializing in the history of immigration, David Assouline is the co-author of Notre Printemps en hiver (Éditions La Découverte, 1987), of the trilogy Un siècle d’immigrations en France: De la mine au champ de bataille (1851-1918), De l’usine au Maquis (1918-1945), and Du chantier à la citoyenneté (1945 à nos jours) (Éditions Syros. 1995-1997).

David Assouline wrote and directed the documentary film Entre Paradis perdu et Terre promise on the history of the Jews of Morocco (60 minutes). Introducing this nostalgic documentary, Béatrice Bantman et Nicolas Santolaria wrote in Liberation, the following introduction: (55)

[‘’What remains of Sefrou, the little Jerusalem of Morocco, the oriental earthly paradise adored by Colette? A memory, a sweet wound for the children of the thousands of Jews who once lived in this small Moroccan town near Fez. “The land of Israel was here” says Moshe, one of the last Jews to leave Sefrou for Israel. They left one after the other, driven out by Moroccan independence, the wars in the Middle East and the widespread fear that overcame the sweetness of living together, Jews and Arabs, without fuss. David Assouline’s documentary should be seen for the beautiful images of this peaceful past in the medina and to discover, once again, that the drama of integration is not necessarily played out where we expect it to be. For the elders of Sefrou, the promised land had a bitter taste. “I was a master, I became a servant”, says one of them who tells of the humiliations, the morgue of the European Jews and the young girls who turn their backs when they say they are Moroccan. In the end, he came to terms with the fact that “at least my sons were not called dirty Jews”.’’]

”Que reste-t-il de Sefrou, la petite Jérusalem du Maroc, paradis terrestre oriental adoré de Colette? Une mémoire, une douce blessure pour les enfants de ces milliers de juifs qui vécurent autrefois dans cette petite ville marocaine proche de Fès. «La terre d’Israel était ici» dit Moshe, un des derniers Juifs à avoir quitté Sefrou pour Israël. Ils sont partis les uns après les autres, chassés par l’indépendance marocaine, les guerres du Moyen Orient et cette peur diffuse qui a eu raison de la douceur de vivre ensemble, Juifs et Arabes, sans histoires. Il faut voir le docu de David Assouline pour les belles images de ce passé paisible dans la medina et découvrir, une fois de plus, que le drame de l’intégration ne se joue pas forcément là où on l’attend. Pour les anciens de Sefrou, la terre promise a eu un goût amer. «J’étais maître, je suis devenu serviteur», dit l’un d’eux qui raconte les humiliations, la morgue des juifs d’Europe et les jeunes filles qui tournent le dos quand on dit qu’on est Marocain. Pour finir par s’en accomoder, «Mes fils, au moins n’ont pas été traités de sales juifs».”

Author of several researches, studies and exhibitions on the repression of Algerians in France during the Algerian War, he published a collective work, with Mehdi Lallaoui, À propos d’octobre 1961 (Éditions ANM, 2001). David Assouline was the first to find and have published the archives of the Paris public prosecutor’s office proving irrefutably the death of dozens of Algerian FLN militants following the police repression under the orders of Maurice Papon on October 17, 1961.

The departure of the Jews of Sefrou

What remains of Sefrou, the ‘’Little Jerusalem of Morocco,’’ the oriental earthly paradise adored by Colette? A memory, a sweet wound for the children of the thousands of Jews who once lived in this small Moroccan town near Fez. “The land of Israel was here” says Moshe, (56) one of the last Jews to leave Sefrou for Israel. They left one after the other, driven out by Moroccan independence, the wars in the Middle East, and the widespread fear that overcame the sweetness of living together, Jews and Arabs, without fuss. (57)

The drama of integration is not necessarily played out where it is expected. For the elders of Sefrou, the promised land had a bitter taste. “I was a master, I became a servant“, says one of them who tells of the humiliations, the morgue of the European Jews, and the young girls who turn their backs when they say they are Moroccan. (58) In the end, he came to terms with the fact that “at least my sons were not called dirty Jews“. (59)

On the immigration of the Jews of Sefrou to Israel (Alyah), Yaron Tsur wrote: (60)

‘’L’activité de Lévy n’a pas débuté à Fès, mais dans la ville proche de Séfrou, qui comptait de 4 000 à 5 000 juifs. Lévy y séjourna lors de l’été 1920, peut-être pour ses affaires. À la fin des offices célébrés dans les synagogues, il profitait de la présence de fidèles pour organiser de petites réunions. Il ne mit pas par écrit le contenu de ses discours aux fidèles, ni la manière dont il avait coutume de faire sa propagande auprès des juifs de sa région, mais il décrit la réaction du public à ses paroles : « Toute la population était très émue au point que plusieurs familles respectables liquidèrent rapidement leurs affaires immédiatement après que je les ai quittées, pour monter en Eretz-Israël. » Ses propos indiquent clairement que sa propagande s’inspirait du discours messianique traditionnel. Seul le mélange de l’ancien et du nouveau, c’est-à-dire la croyance dans la vision rédemptrice allant de pair avec une propagande sioniste et moderne, peut expliquer la décision immédiate de plusieurs familles aisées de prendre ainsi la route. La motivation économique ne représentait pas pour elles le facteur décisif.’’

[‘’Levy’s activity did not begin in Fez, but in the nearby town of Sefrou, which had 4,000 to 5,000 Jews. Levy stayed there in the summer of 1920, perhaps for business. At the end of the services in the synagogues, he took advantage of the presence of the faithful to organize small meetings. He did not write down the content of his speeches to the congregation, nor the way in which he used to propagandize the Jews of his region, but he describes the reaction of the public to his words: “The whole population was so moved that several respectable families quickly liquidated their affairs immediately after I left them, to go up to Eretz-Israel. “19 His words clearly indicate that his propaganda was based on the traditional messianic discourse. Only the mixture of the old and the new, i.e., the belief in the redemptive vision coupled with modern Zionist propaganda, can explain the immediate decision of many well-to-do families to take the road in this way. Economic motivation was not the decisive factor for them.’’]

The history of Sefrou according to its Jewish inhabitants

History tells us that the inhabitants of Sefrou practiced the religions in vogue during ancient times: Christian, Jewish, and Majousse (also spelled Majus) or magism, worshippers of fire and offered their children in the holocaust; this practice is prohibited by Jewish and Muslim religions.

It is probable that to escape this barbaric practice, which takes its name from “Berberia”, the ancient name by which Morocco was designated (mentioned in the Talmud and even in the Bible), the tribes of Philistines or Pelistims in Hebrew, who came from Palestine at various times, became Jews. This fact is unanimously reported by Arab historians and others.

The city of Sefrou was a frequented economic center, being closer to the ancient city of Sijelmassa on the one hand, to Taza (also older) and Debdou on the other hand, without forgetting the center of Volubilis and its region, as well as the city of Fez. The city of Sefrou is one of the seven famous cities of ancient Morocco.

As everywhere in Morocco, historical and linguistic vestiges attest to the presence of the Jews in the regions where they settled, and the city of Sefrou is not exempt from this rule, for its main river known as Oued Aggay bore also the name of “Oued Lihoudi” or “River of the Jew” which indicates that the river belonged to the Jews since their mellah was built on its bank

in parallel with the name “Aggay” of Tamazight/Berber origin, it is also found in Greek, and it is, also, a word used in the Talmud by the Jews, “aggia” which means capture or gathering of water. It is admitted that the Jews along with the Phoenicians frequented Morocco before the Greeks, the oldest name of the Arabized river must be that of “Oued Lihoudi.

The Israelites of Sefrou come for the most part from the region of Tafilalet and that of Debdou; both are known for their demanding, stubborn character and sometimes harder in business or in discussions, than those who come from the neighboring regions, Bahlil, Azrou, etc. or even from Fez.

The number of Israelites in Sefrou, around 1900, was according to a local chronicle of 2,200, forming 550 families, occupying 64 houses composed of 542 rooms or bedrooms; there were five synagogues (in Fez 15 at the same time). (61) Apparently, this figure, which was exactly counted, is double that indicated by Charles de Foucauld, who was passing through Sefrou at the same time. (62)

At the arrival of Moulay Idriss II, the Israelites of Sefrou lived in ksar Tofr and ksar al-Koufâr (Ksar of the miscreants). The Mellah of Sefrou was built during the reign of the Marinids.

The trade of the Israelites was mainly with the neighboring tribes. Their habits and way of life were those of country people, even in their clothing, except for rare exceptions. Rabbis, notables, children, and women always wore traditional clothing on the Shabbat and Jewish holidays.

The life in the open air, in the country for the men, the needs of housework, laundry, wool washing, and other occupations on the banks of the Oued Lihoudi, for the women, gave them robust and flourishing health; these habitual occupations from their young age made them very active and courageous, compared to the Jewish women of the other cities of Morocco. Accustomed to these sober conditions, both men and women lived very long lives. It is said that a Jewish woman who had run out of pepper for her soup went on foot to buy it in Fez and returned during the day to resume her occupations.

Many women came to work in Fez during the week and returned to Sefrou on Friday to celebrate the Shabbat; others settled in front of the door of Bab Semmarine in Fez, to sew and mend the clothes of passers-by at a suitable price. Bab Semmarine is the entrance to Fez-Jdid, on the side of the mellah of Fez; Jewish women from mellah worked as menders and lined up in two lines at Bab Semmarine while waiting for Muslims from Fez-Jdid to call on them to mend their clothes: this explains why women from Sefrou were also at Bab Semmarine. A team of these women settled for the washing of wool in Aïn Tchoutcha (source of the mulberry tree) at the same time as the Muslim women in Fez. This source and its destination still existed until recently in the shallows of the Bab Jiaf square, recently occupied by the municipal auction of Fez. It could be Aïn Touta, “tut” being the Moroccan Arabic name for the blackberry.

The Jews of Sefrou were specialized in the work of copper objects used for ritual needs (lamps of ancient form to celebrate the festival of Chanukkah (or Hanukkah), chains used to hang vases in the synagogues, etc.) or for the household, leather bags and slippers, weaving of woollen carpets, trade of carpentry wood that the proximity of the forest regions of Guigou and Azrou facilitated, charcoal, etc. The blackberries and cherries of Sefrou were particularly famous and were always sought after by the inhabitants of Fez and other regions of Morocco, they were picked up and sold by Jewish people.

For the trips between Fez and Sefrou, one went on a mule; the transport of wood and coal was done by caravan, on a donkey, the men travelled on foot. During the periods of hostility, the muleteers paid an illegal tax called “zttata” (63) under the threat of the usual expression at the time “zttata walla takshât” which means “payment or stripping” while passing at the place called “Ayoun Smar” located at approximately halfway. The payment of the “zttata” guaranteed that the caravan would not be disturbed on its way. It goes without saying that this payment applied only to the muleteers or Israelite travelers because it could not be demanded from the tribesmen for fear of reprisals.

When an Israelite merchant from Sefrou became rich or if the development of his business required it, he settled permanently in Fez, as such many families considered as a Fassi originated from Sefrou. Sometimes, the opposite happened and some families from Fez moved to Sefrou to benefit from a simpler and more economical way of life.

An unfortunate event took place in the year 5650 of the Hebrew era, that is to say in 1890, when one Friday evening the river overflowed its banks following heavy rains and a flood invaded the Mellah, this district being on the bank of the river. There were many deaths and considerable damage. Several teams of Israelites from Fez left the next morning, a Saturday, to help their co-religionists in the neighboring city.

The same event occurred in 1950. The flood on the eve of the Israelite festival of Sukkot or huts destroyed several houses and many people died. The flood spread to Fez, demolished a bridge on its way to the new city, and filled a huge basin-like ravine between the new city and the medina, which would otherwise have suffered an unprecedented disaster. In Sefrou, the streets of the medina and the mellah were washed away in some places to a depth of more than two meters: more than 60 houses and stores collapsed. The violent storms of September caused damage in Immouzer and in Fez where Oued al-Mehraz overflowed, flooding the Sidi Brahim district and ravaging everything in its path.

Since the old days, the wealthy families of Fez went to Sefrou during the hot season to benefit from the excellent and healthy climate and the green gardens around the mellah. During the month of May, Jews come on pilgrimage to the tomb of an unknown Jewish saint, which is located in the cave of Kâf Lihoud (Jbel Binna) at the bottom of the mountain, next to the present Israelite cemetery. The interest of the cave lies in the cult of which it is the object. Pregnant women make pious visits there so that their delivery is easy. Sterile women bring candles to become fertile.

The Jews of Sefrou spoke either Arabic (64) or Tamazight or both because in their commercial daily work they had to deal with Berber farmers from the plain surrounding the city and in their daily life Arabic was the medium of communication while Hebrew was used for prayers and Jewish holidays.

In reference to the linguistic reality of Moroccan Jews, Simon Levy, a Moroccan Jewish linguist, writes: (65)

‘’Why do some Jewish communities such as those of Midelt, Demnat, and Tahala remain Arabic-speaking in a Berber-speaking environment? Why has Judeo-Spanish (ḥakitiya) survived in Tetouan and Tangiers but not in Fez or Meknes? How did one community influence another? And above all, how did they arise in particular areas, at what time, and from which center? Why does the Jewish dialect of Marrakesh contain so many characteristics of urban Arabic while the speech of their Muslim neighbors has so many rural features? To answer these questions, we need to start by sketching out the historical and social context of this study and by undertaking a history of Jewish settlement in the host country while avoiding all Manichaean dualism or ghettoization.’’

The Jewish community of Sefrou celebrates the Throne Day in 1957

The President of the Jewish Community Committee Rahamin Tobaly and Chief Rabbi David Obadia, surrounded by the members of the Committee, received in the premises the President of the Communal Council of Em Habanim, His Excellency El Hassane El Alaoui, Pasha of the City, accompanied by local authorities and Muslim and Jewish notabilities.

In an emotional and warmly applauded speech, which preceded the traditional prayer on the occasion of the Throne Day, Rabbi David Obadia recounted a parable from the Talmud. He compared the wishes made by the people of Morocco to those made by a traveler lost in the desert and hungry and thirsty. When he looked up to heaven to pray to God, he saw a tree covered with green leaves, succulent fruits and at the foot of which flowed a spring. He ate and drank and then addressed the tree:

“What prayer can I ask God for you? Green leaves, delicious fruits, water at your foot you have – I only wish that each of your offshoots would give a tree in your image”.

Rabbi David Ovadia in his prayers said:

‘’We all, like this traveler, addressed this prayer to our Most High God during the lifetime of our King Mohammed V and God the Merciful answered our prayers. May God give him long life, honor, glory, guide him and enlighten him in his actions, and may his reign be one of progress, well-being, freedom and peace.’’

On what concerns the daily affairs and welfare of the Jewish community, Rabbi David Obadia wrote the following letter to the Pasha (Mayor) of Sefrou:

‘’Sefrou, January 23, 1957

Mister the Pasha of the City of Sefrou,

Excellency,

I would be very grateful if you would grant a weekly day of rest, in addition to the Sabbath, to Mr. Mardoché Haroche, sweeper at the Mellah.

The latter works half a day on Saturday, which is contrary to the Jewish religion.

Counting on your customary benevolence, please accept, Excellency, the expression of my respectful greetings.

signed: Obadia David.’’

Two days later the Pasha answered favourably to the request of the Rabbi:

‘’Sefrou, January 25, 1957

The Pasha of the City of Sefrou to Mr. David Obadia Chief Rabbi of Sefrou

Further to your letter dated January 23, 1957 concerning the subject mentioned in the margin, I have the honor to inform you that I do not see any inconvenience for the worker Mordechai Harroch to take his rest on Saturday in exchange for Sunday.

Please accept, Sir, my best regards.

Signed: El Hassane El Alaoui’’

On the sad occasion of the passing away of the president of the Jewish community of Fez Oujda and Sefrou, Dr. Armand Guigui, on December 2019, His Majesty King Mohammed VI sent a message of condolences and compassion to his family members. In this message, the Sovereign said he learned with deep emotion the death of Armand Guiguin, may God surround him with His great mercy.

In this painful circumstance, H.M. the King expressed to the members of the family of the deceased, and through them to his relatives and to the members of the Moroccan Jewish community, his deep condolences and his sincere feelings of compassion, following this cruel loss, imploring the Almighty to grant them patience and consolation.

The Sovereign recalled the qualities of the deceased, invoking his patriotic spirit and his attachment to the constants and sacred values of the Nation and to the Alaoite Throne, praying to God to accept the late Guigui in His Celestial Kingdom and to reward him amply for the commendable services rendered to his country.

The suq of Sefrou

After his multiple academic works on Islam in Indonesia, Geertz chose the city of Sefrou at a time when its Jewish inhabitants had almost all emigrated to Israel following the Six-Day War in the Middle East and the need to make their Aliyah.

Geertz, his wife Hildred, and his friend Rosen Lawrence were interested for many personal and academic reasons in studying the economy and society of this thousand-year-old city known for its tolerance and interfaith communication. Before their arrival, the city had attracted many civilian, military and religious travelers obsessed with its magic and exoticism, but never academics.

For Geertz, the bazaar is a “key institution.” The one in Sefrou, is of relative importance on the scale of Morocco. It includes some 600 established stores, forty professions, 300 workshops and a large number of mobile actors. Geertz noted that this market is sorely lacking the average customer. The quasi-totality of its actors, indeed, take part there, simultaneously, in two titles: salesmen and purchasers. They are “intimate antagonists”, who are constantly putting their own personal status at stake.

This interdependence is the basis of the very specific relations of client vs salesman: rather than vertically linking clients and bosses, these erect the principle of mutual dependence between clients and clients, obliged and obliged, service providers and service providers. Such relations can therefore only be equivocal, situational, and, above all, reversible. It is their constant reproduction, in fluidity and flexibility, that gives meaning to the market as a whole. Thus, nothing prohibits breaking with a seller or a buyer without jeopardizing the principle of the mutual dependence on the intimate antagonists.

When Geertz started his fieldwork in 1967 there were 600 Jews and the number dwindled to 200 in 1972. (67) He goes on to say that back in 1950, the density of the population was so high, that Jews moved to the French Ville nouvelle. The economic situation in the city became precarious and such Jews either left for Israel, France or bigger Moroccan cities such as Fez and Casablanca: (68)

‘’The diminution- and probable demise- of the Jewish community of Sefrou is not the result of any breakdown in Muslim-Jewish relations, but it stems from the Jew’s general uncertainty about the stability of the Moroccan economy and the opportunities that would be available to their children in contemporary Morocco. During the period of fieldwork, the Jewish schools still operated and Jews were still seen in the marketplace, but the familial hierarchy, the elaborate internal institutions, and the economic importance of the Jewish community, like the mellah community itself, were almost entirely gone.’’

The Jews played a major role in thesûqeconomic business of the city and its prosperity. They were the link with the outside world, mainly the countryside. A sort of extension of the merchant activities of the bazaar to the countryside. In this regard, Geertz distinguishes two type of Jews: the sitting (gles) Jews and the riding (rkeb) Jews.

Geertz speaks of these two categories of Jews of Sefrou as follows: (70)

‘’The riding Jews were, in fact, riding camp to camp, suq to suq, virtually the whole of the year, returning to Sefrou for any length of time only during the two main holiday seasons. In town, the sitting Jews sat, sources not only of capital for the riding Jews, but of food and housing, and indeed of a whole range of welfare services, for the latter’s families, including governance of their morale and religious life. Though not explicitly conceived as such, the riding Jews were almost as much the sitting Jews’ servants as their agents.’’

And he goes on to further explain the place of the Jews in the bazaar economy: (71)

‘’Towards the artisans, most of whom, especially in shoemaking and tailoring, were also dirt poor, the financiers had a similar relation, capitalizing them, engrossing their output, and providing for their subsistence almost as an extension of an expanded family economy. The welfare hierarchy that governed community life generally provided the framework for commercial relations within the community as well. Outside the community, whether dealing with a Berber pastoralist, a town weaver, or a Fez importer, the Jews fitted as mentioned, into the more general structure of the bazaar as a whole. Indeed, in Sefrou at least, trying town and country together, permanent suq and periodic, they helped create the bazaar.’’

For Geertz, the Jewish society was hyper-organized and that helped it to survive in a Muslim environment but more than that be the motor of the bazaar economy in so much as it could evolve in all the areas in which Muslims could not either for religious reasons or practical economic expertise.

Geertz describes the Mellah of Sefrou in the following terms: (72)

‘’That world was marked by three main characteristics: hyperorganization, thoroughgoing plutocracy, and intense piety. Pressed in behind the wall of their own quarter, the mellâh, where, until the Protectorate they were obliged to live, the Jews seem to have concentrated their social personality as the Muslims diffused theirs. Locked each night in their quarter (no-non Jews could enter after dark), an increasingly crowded and unexpendable ghetto, whose buildings raised up like miniskyscrapers to accommodate the pressure, the Jews developed a society whose close counterpart, the religiosity perhaps somewhat aside, seems to be the merchant oligarchies of Rennaissance Italy.’’

Within the bazaar economy, the interrelationships between the different types of people who were there – sitting Jews (gles), riding Jews (rkeb), Amazigh chiefs, Arab notables, Saharan mule skinners, and a number of other types not yet mentioned – were complex, cross-cutting, and anything but remote. The economy of the bazaar was multicolored from the start: different varieties of people entered it to varying degrees, in different ways, and with not entirely complementary views of each other. (73)

For Mourad Moulai Hadj, the opus of Geertz et al. was an intense anthropological work that linked culture, religion, history and ethnography in the study of the people of Sefrou and their environment through the study of their sûq and its economic and social correlations: (74)

[‘’The souk of Sefrou was a field of study that contributed to the development of an anthropological approach linking the economic, the historical and the cultural to the daily life of individuals. The methodological contribution of Geertz in this research through its observation and thick description, was able to give birth to an anthropological current favoring the understanding of the meaning that the individuals give to the symbols, and the interpretation of culture.

The identity and cultural belonging of the people of Sefrou was an element of analysis and excavation from the use of the term Nisba, in order to discover the link of the trade with a religious and cultural heterogeneity of the merchant class or an ethnic mosaic in the Souk.’’]

‘’Le souk de Sefrou c’était un champ d’étude qui a contribué au développement d’une approche anthropologique reliant l’économique, l’historique et le culturel à la quotidienneté des individus. L’apport méthodologique de Geertz dans cette recherche à travers son observation et description dense, a pu donner naissance à un courant anthropologique favorisant la compréhension du sens que donnent les individus aux symboles, et l’interprétation de la culture.

L’appartenance identitaire et culturelle des gens de Sefrou a été un élément d’analyse et de fouille à partir de l’utilisation du terme Nisba, afin de découvrir le lien du commerce avec une hétérogénéité religieuse et culturelle de la classe marchande ou une mosaïque ethnique dans le Souk.’’

The city might be small in size and importance but it is ‘’thick’’ in cultural symbolism and anthropological significance. The ethnic mosaic created is reproduced and organized around the division of labor that inculcates a perception towards the different socio-ethnic groups and influences the social stratification and the social position of these groups in the society.

Mourad Moulai Hadj goes on to say in this regard: (75)

[‘’This thesis led Geertz to develop a description of religion and its effect on the organization of merchant activity, social, cultural and cultic activity of two communities: the Muslims and Jews. For this purpose, Geertz used the religious institutions (Habous, Zawiyas and Hinta) in the case of Muslims and (the community council and the Riba) for the Jews, to analyze the social and cultural interactions in the two communities. Moreover, this religious system does not exist without an interdependence with the economic one and by this Geertz shows us a division of labor between the two communities; Muslims oriented towards El Hirfa and the craft industry and Jews towards commercial activity.’’]

‘’Cette thèse menait Geertz à développer une description de la religion et son effet sur l’organisation de l’activité marchande, sociale, culturelle et cultuelle de deux communautés : les musulmans et les juifs. Pour cela, Geertz utilisait les institutions religieuses, (Habous, Zawiyas et Hinta) chez les musulmans et (le conseil communautaire et le Riba) chez les juifs, pour analyser les interactions sociale et culturelle dans les deux communautés. En outre ce système religieux n’a pas d’existence sans une interdépendance avec l’économique et par là Geertz nous montre une division de travail entre les deux communautés ; des musulmans orientés vers El Hirfa et l’artisanat et des juifs vers l’activité commerciale. ‘’

Sefrou and the caravan trade with Africa

Anyone who visits Sefrou will be struck by the number of caravanserais (funduks) that exist in the Medina, today most of them are converted into kissariyas, mini inner markets, or markets for a special guild. These caravanserais in the past were inns for caravan Jewish guides and caravan merchants that traveled all the way to Timbuktu to deliver goods in exchange sometimes for gold (this is known today in the politically correct jargon as the’’unfair trade’’). (76)

The megorashim Jews came to Sefrou in 1493 and were joined later on by the Tafilalet Jews who escaped Arab persecution in that area. While the megorashim came from al-Andalus with expertise in trade and business, the Tafilalet Jews were expert guides and had great knowledge of commerce with African tribes. Their co-presence in Sefrou, a city with a strong bazaar economy incited to mount caravan trade venture with Africa.

Larbi al-Adlouni (1912-1995), a religious scholar who lived on zankat Chebbak,near Bab Lamqam in Sefrou: (77)