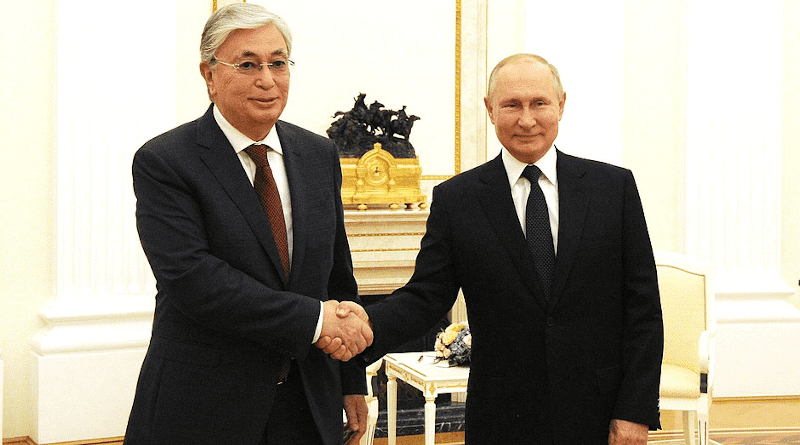

Is Tokayev A Friend Of Russians? – OpEd

Since last August, Russian-Kazakh relationship has appeared to grow more problematic with each passing week. As far as is known, no specific problems in this regard have been raised at the high-level meetings between the leaderships of the two countries. Yet in the media and at the public level, the picture is different.

The sides are exchanging blows there. In a figurative sense, of course. And, as always happens in such matters, those verbal battles were initially spearheaded by the Russian side, which has now substantially increased the scale of its offensive activities. The Kazakhstani side has occasionally taken countermeasures against them. The Kazakh public figures, journalists and ordinary people have once in a while responded to them, sometimes by bringing counter-allegations. But not much else.

Anyway, the Kazakh reaction to the information campaign, launched and fanned by media and political circles close to official Moscow, has been and remains small in scale. The Kazakh officials and much of the Kazakhstani state media still refrain from engaging in active debate with their Russian counterparts over that topic despite the fact, that the latter ones have already accused Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, Kazakhstan’s current president, of supporting the Kazakh nationalism that is, shall we say, unsympathetic to Moscow.

Here is a recent example of it. Pravda.ru. which is privately owned and has international editions published in Russian, English, French and Portuguese, in an article titled “Tokayev is not a friend of Russians” (“Токаев русским не друг – pravda.ru”) said: “On October 21, President of Kazakhstan Kassym-Zhomart Tokayev delivered a speech at an expanded session of the Assembly of People of Kazakhstan. This is a consultative and advisory entity under the President, whose task is ‘to promote the development and implementation of state policy in the sphere of inter-ethnic relations’.

It was expected that the president would respond to the provocations by Kazakh nationalists against Russians and Russian speakers, which have become more frequent recently.

The President instructed the Ministry of Education and Science ‘to carefully study the experience of multilingualism around the world and replicate it in our country’, and the Ministry of Information and Social Development to develop a ‘scientifically grounded approach to deal with the inter-ethnic sphere’.

‘This is a very delicate area. It does not tolerate amateurism and populism. Only qualified specialists should work there’, the president said.

Tokayev’s statements are more likely to be a posturing for Moscow, like, I am dealing with nationalists, what else do you want. But in fact, he will continue to carry out the Kazakhization of the population, its archaization, aimed at ousting the best cadres to Russia and resettling Uzbeks from the southern regions to places in the north of the country where Russians normally live”.

The author of that article therefore concludes that an unfavorable situation is now being shaped in the Republic of Kazakhstan for Russian and Russian-speaking people. Yet how can those outside Kazakhstan verify the extent to which this is the case? Almost all countries outside CIS are getting general knowledge and current information on life in Kazakhstan mostly through Russian language. And Runet (Internet in Russian, i.e. a part of the Internet that uses the Russian language) is, one way or another, controlled by Russian entities. And there, it’s quite hard – in the light of recent developments in Russian-Kazakh relations – to find an unbiased information related to the situation of ethnic Russians [and other minorities] in the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Things need to change in this sphere. For the purpose of objectivity, there is a need to review the situation on the ground, i.e. to take a close look at the activities of the local media, to walk the streets, to visit a number of offices and institutions, to hear politicians and statesmen speak. The functioning of the State and society continues to be based mainly on Russian. The following statement formulated by Ivan Shchegolikhin, a prominent ethnically Russian Kazakhstani writer, is the best proof of this (‘I will not seek victories’, Prostor, #1, 2008): ‘In Kazakhstan, the attitude towards Russians is not as boorish as it is in the Baltic States or Moldova, let alone the so-called brotherly country of Ukraine, where there is the greatest hate against Muscovites… By the way, today there are only two States in the world where the highest authorities are performing all of its activities through Russian language. These are Russia and Kazakhstan’. Ivan Shchegolikhin said those words at a meeting of Vladimir Putin ‘with his Kazakhstani compatriots’ that had been organized by the Russian embassy in Astana (Nur-Sultan) during one of the Russian president’s visits to Kazakhstan. So, to summarize, the idea is as follows. Even according to a local prominent figure of Russian origin, Kazakhstan, to a large extent, still looks like a ‘second Russia’.

Life is of course an evolving process. And now it looks like the situation is slowly starting to change. At least, that is the way it appears. This may be considered as a subjective point of view. But it is unquestionably true that the effect of changing the demographic balance in the republic in favor of the titular ethnic group has been increasingly influencing the Kazakh government’s language policy. That’s precisely what concerns the Russian side most. Apparently, official Moscow want Kazakhstan to continue be looking like a ‘second Russia’.

Yet the situation now seems to be a rather different than at the time when official Moscow could unilaterally impose its ideology and development model on Kazakhstan. During the census compiled in 2009, only 64 percent of the population said they were fluent in spoken and written Kazakh, compared with 85 percent in Russian. Since then the ethnic balance has notably shifted, with Kazakhs now making up almost 70 percent of the republic’s population of over 19 million, while ethnic Russians account for less than a fifth (18.85 per cent). Reuters, in a report published on 1 March 2018 and entitled ‘Kazakhstan says Russian not banned from government after all’, said: ‘Language is a sensitive issue in the oil-rich former Soviet republic of 18 million, where ethnic Russians make up a fifth of the population and many ethnic Kazakhs, including senior officials, also speak Russian more fluently than Kazakh.

Members of Kazakhstan’s cabinet and parliament have usually spoken whichever language they were more fluent in during public meetings, although it has become customary among government ministers to at least open their speeches in Kazakh. On Monday, however, Nazarbayev’s office said in a statement he had instructed ministers and deputies to only use Kazakh in their work – while providing simultaneous translation to those not fluent in it. The following day, all, but one, cabinet members spoke exclusively Kazakh at a weekly meeting which was broadcast live. But later this week, senior officials… said his instructions had been misinterpreted and were not an outright ban on the use of Russian.

‘…It is clear that there is no ban on speaking Russian in parliament and government’, Talgat Zhumagulov, chairman of the International Information Committee at Kazakhstan’s foreign ministry, told Reuters in an email’.

The above-mentioned activities notwithstanding, the Russian language has continued to dominate. It is the obvious thing that doesn’t require further proof.

Right, well, if that’s the case, what exactly is the truth of the advocates for the interests of the Russian and Slavic communities? It is an undeniable fact that millions of ethnic Russians and other Russian-speaking Europeans left Kazakhstan. Tens of thousands of such people have been packing their bags and leaving abroad every year. The process is ongoing, and apparently no end is in sight. The underlying explanation for the migratory flow from the Republic of Kazakhstan to the Russian Federation and other European countries may not always lie in the human desire to return to the historical homeland. Most of those people actually believe that they do not have any perspective in the Central Asian country.

Kazakhstan is now a lot different than it was before the dissolution of the USSR. At that time, there was a tendency, especially among the local Russian (European) and Caucasian communities, to look down on persons belonging to Kazakhstan’s indigenous ethnic group. Such behavior, demonstrating contempt for Kazakhs, have been practiced long into the post-Soviet period. Let us take a look at some specific examples of such contemptuous attitudes and rejection in the Russian media’s display. Here is what, for instance, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, a native of Almaty and leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, says about the indigenous people of the country where he was born and raised: ‘Semi-literate and completely illiterate residents of auls (traditional villages) have been admitted to universities. They come to the city. They shake out their felt rugs. You know what all’s out there. People of a completely different culture, and they are drawn into city life’.

And there is another example. At a meeting with journalists in 1998, Vladimir Rutskoy, then the governor of the Kursk region and ex-vice-president of Russia, reacted to some statement made by President Nazarbayev as follows: ‘I don’t get that kind of impudence. We have got these people down from the donkeys and taught them how to use toilet paper’.

Everything has changed dramatically in recent years. For the people with the above-mentioned way of looking at things, it is difficult to accept this state of affairs, and adapting to new conditions is painful.

‘One stick, two strings, I am the master of the whole country’, Kazakhstani Russians used to sneer during the Soviet period, referring to the average Kazakh with his ethno-cultural dombra (a long-necked musical string instrument). But now what they laughed at has become a reality. One can imagine what these people must be feeling under such circumstances. In this case, the fact that the Russian language has retained and expanded its position is not enough for them to be calmed down and appeased. It is only able to slightly sweeten the pill. Yet the latter one does not cease having bitter taste…

We are setting out all this solely with the objective to make a contribution to clarifying the issue and not to plunge into subjectivity. If we have managed to bring at least a bit more clarity to this seemingly paradoxical situation, that’s good enough.

*Akhas Tazhutov is a political analyst